Unit 10: Expectation and Anticipation

Synopsis

Try singing “Happy Birthday”, but instead of finishing the song, stop just before the final phrase “happy birthday to you”. It’s almost painful not to continue. Our desire to “complete” a particular melodic, harmonic, or rhythmic sequence is strong; as we listen and make sense of what we are hearing, we are continually anticipating what will come next, just as with language. When our predictions fail, we experience arousal and affect, making the systematic violation of expectation a powerful dimension of musical expression. While there are many open questions regarding the ways in which our sense of expectation works, there are a number of precise models that we can use to predict expectation in musical melodies and rhythms. For example, the Gap-Fill model suggests that a large melodic interval is usually expected to be followed by a series of small intervals in the opposite direction that “fill the gap”. Statistics also seems to play an important role, as our expectation seems to be correlated with the likelihood of an event.

Expectation

In this unit on expectation and anticipation, we will talk about:

- functions and demonstrations of expectation and anticipation

- theories of expectation

- methods of exploring expectation and anticipation

- types of expectation and the learning of expectation

What is expectancy?

Expectancy is a state of anticipation for the future. While expectancy is commonly conceived as a generalized state, expectation is a more specific sense of having some knowledge or prediction of which events will occur in the near future (e.g. Eerola, 2003). Thus, one can have expectations for which note or chord will come next in a piece of music, but a change in dynamics in music, for example, changes one’s expectancy for loud music.

Some quotes on expectancy, expectation, and anticipation:

- “A mind is fundamentally an anticipator, an expectation generator.” Dan Dennett, philosopher. 1996

- “Expectancy typically refers to an anticipatory orienting of attention.” Mari Reiss Jones, psychologist. 1991

- “The story of expectation is intertwined with both biology and culture.” David Huron, music cognition researcher. 2004

Here is an example of three different conditions of expectancy in music. Listen to the following three clips of music. Which one sounds the most expected? Which one sounds most unexpected?

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Why do we study expectation?

Expectations are evolutionarily adaptive because the ability to form expectations accurately for future events facilitates us in our perception and action. To illustrate the evolutionary advantage for expectation, imagine the following scenario. You are driving your car up the street when you see this:

What would you do?

Most people would opt to stop their car immediately. This is because prior knowledge has equipped you with a high expectation that the boy would run into the street to catch the ball, and if your car continued up the street you would hit the boy and cause a tragic accident. In this case, as in many real-life situations, the formation of expectation saves you from trouble and is thus evolutionarily adaptive.

Of course, the ability to form expectations is useful only if your expectations are mostly correct. If you somehow had an incorrect expectation for the child in the above picture to run away from the ball instead of towards it, you would not stop to avoid the child and thus your expectation would be of no help.

Expectations are also more useful in a world that is predictable. If children in the world were equally likely to run away from balls as toward them, your expectation for the child to run toward the ball may prove to be inaccurate; thus your stopping the car would only avoid an accident some of the time. While the high motivation to avoid an accident would lead most people to stop the car anyway, the relative likelihood of an accident is still smaller as the child becomes less likely to approach the car.

Expectations are everywhere in music and language. A simple linguistic example goes as follows:

I

take

my

coffee

with

cream

and

socks.

The word “socks” at the end of the sentence is a violation of expectations. Your knowledge of the world, and of the English language, has equipped you with a strong set of expectations that a) “socks” does not form a good ending to the sentence, and b) coffee does not taste good when taken with socks.

Expectations also play a strong role in our perception and cognition of music. When listening to music, one necessarily forms expectations for sounds that are about to occur next. Consider the following example:

Listen to the original melody:

|

| |

What would you expect to hear next?

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

While 1 seems to be the most obviously expected answer, 2 was the more artistically interesting, albeit slightly unexpected. Choice 2 was in fact used in the actual recording of Mozart’s Twinkle Twinkle Little Star Variations. This example shows that it is the slight variations, the slight manipulations of expectations, that we find most interesting and artistically appealing. Thus, the ability to form expectations has been proposed as the source of emotion and meaning in music (Meyer, 1956).

Theories Of Expectation

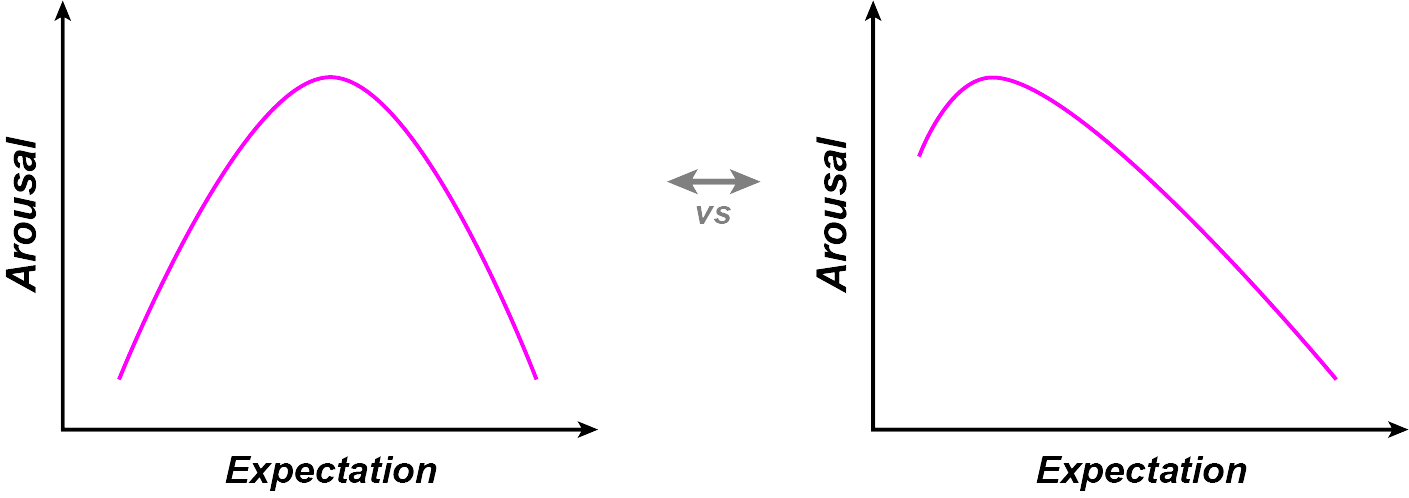

To date, a number of theories have been proposed to describe and understand our experience of musical expectation. The first (and perhaps most influential) of such theories is the Expectation-Arousal theory by Leonard Meyer (1956), which generally posits that the systematic violation of expectation leads to arousal. This theory could be applied to harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic factors, but is a descriptive theory rather than a formally defined set of predictions.

Meyer’s student Narmour (1990) proposed a more formal theory to account for expectation for melody. Narmour’s Implication Realization Model defined a formal set of rules, mainly relating each interval to the next.

More recently, (Huron, 2006) proposed that Gap Fill and Regression To The Mean may be a parsimonious account for expectancy in music, which makes similar predictions as Narmour’s theory (parsimony in psychology entails identifying the simplest and most accurate explanation for brain processes and human behaviors). The relative predictive powers of the Implication Realization Model and Gap Fill are as yet unclear.

In another line of research, Jones (2002) proposed the Dynamic Attention Theory to account for Expectancies For Rhythm. Their model is mostly used to account for rhythmic expectancies such as our internal anticipation for regularities in rhythm and meter.

Expectation and Arousal

Meyer (1956), in his seminal book Emotion and Meaning in Music, proposed that systematic violations of expectations lead to increased arousal, from which affective experience is derived. These expectations are implicitly learned, i.e. acquired without awareness of the listener, and may be applicable to music as well as to other modalities.

Although the model allows for many possibilities, the exact relationship between expectation and affect was not formally defined in the Expectation-Arousal theory. Thus it is unclear exactly what degree of expectation leads to maximal arousal; nor it is clear how expectation can be systematically manipulated.

Three possible functions relating expectation and arousal. Meyer’s (1956) Expectation-Arousal theory does not differentiate between these three predictions.

Nonetheless, we know that expectancy and affect are indeed highly related. Consider the following three chord progressions (they are the same ones from earlier. Which one do you prefer?

- High expectation

- Medium expectation

- Low expectation

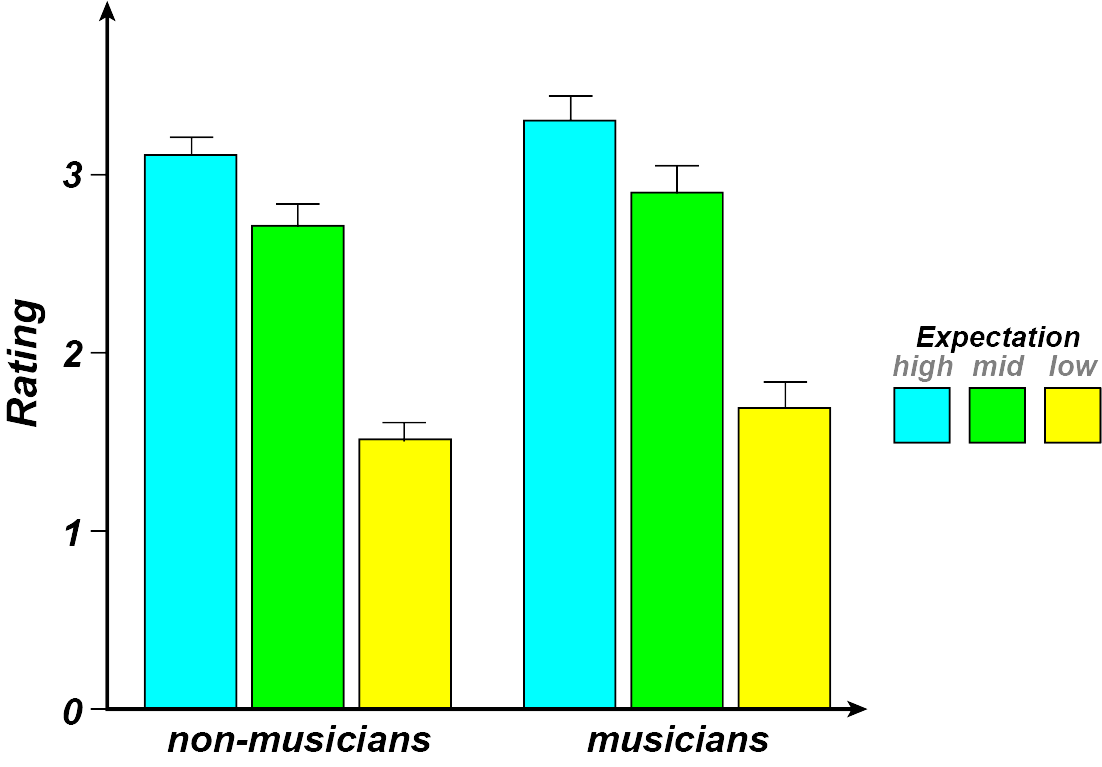

The following graph represents musically trained and untrained subjects’ preference ratings for the three chord progressions. Results show that expectation has a large effect on people’s ratings, but musical training does not.

(image source: Loui & Wessel, 2007)

Expectation For Melody

To date, the most well-specified models for musical expectation mostly refer to expectation for melody. The Implication Realization Model, first proposed by Narmour (1989), is a formal set of rules defining interval directions and sizes in melodies. In contrast, (Huron, 2006) has discussed Gap Fill and Regression To The Mean (or more precisely Post-Skip Reversal) as parsimonious theories to account for melodic structures. See chapter 8.2 in Unit 8 (Melody and Gestalt) for an in-depth look at Implication Realization Model and Gap Fill.

Expectancies For Rhythm

The theories discussed above, such as Implication Realization and Gap Fill, mostly have to do with melodic expectancy. In addition to expecting what musical events occur, however, it is important to examine our expectancy for when they occur. These expectancies, typically dealing with rhythm, meter, and duration, have also been explored, notably by Jones et al (e.g. Jones & Boltz, 1989) in their Dynamic Attention Theory (see below) and by Desain and Honing (2003) in their work relating rhythm perception to meter.

Desain and Honing’s work shows that rhythms can be perceived categorically, and that the perception of rhythms and note durations is highly dependent upon expectancies set up by a metric context.

Dynamic Attention Theory

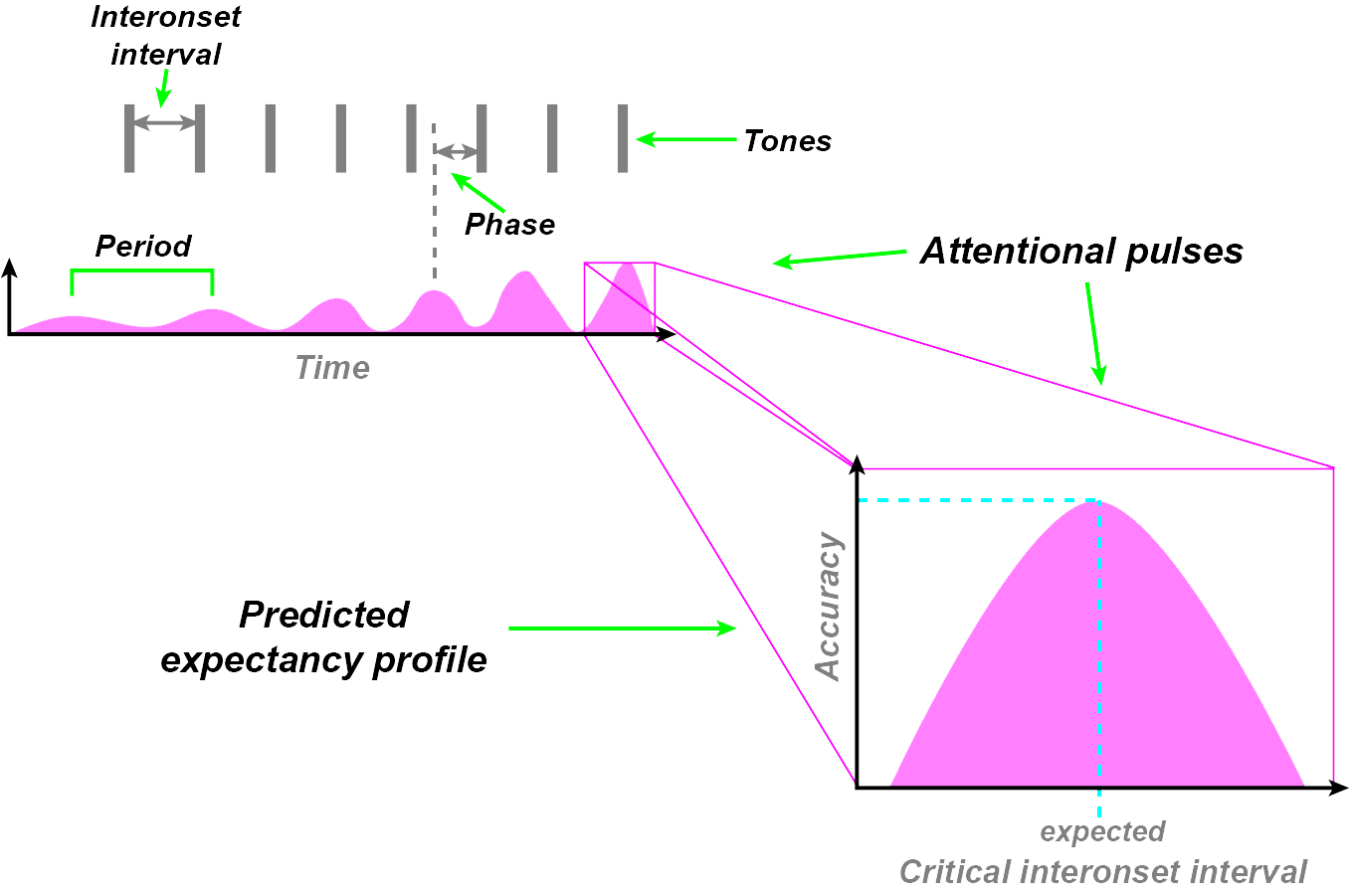

In the Dynamic Attention Theory (Jones & Boltz, 1989) and subsequent work, Jones et al propose models to account for the main observation: that perception and memory are most accurate for events occurring at an expected time. Thus, Jones et al (2002) proposed that expectation heightens attention, whereas attention facilitates perception and memory.

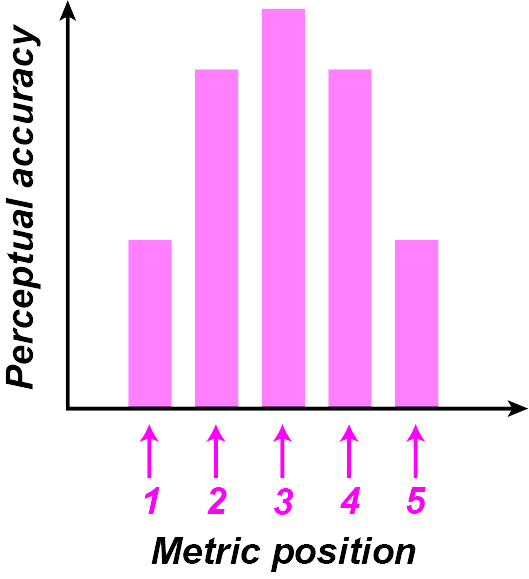

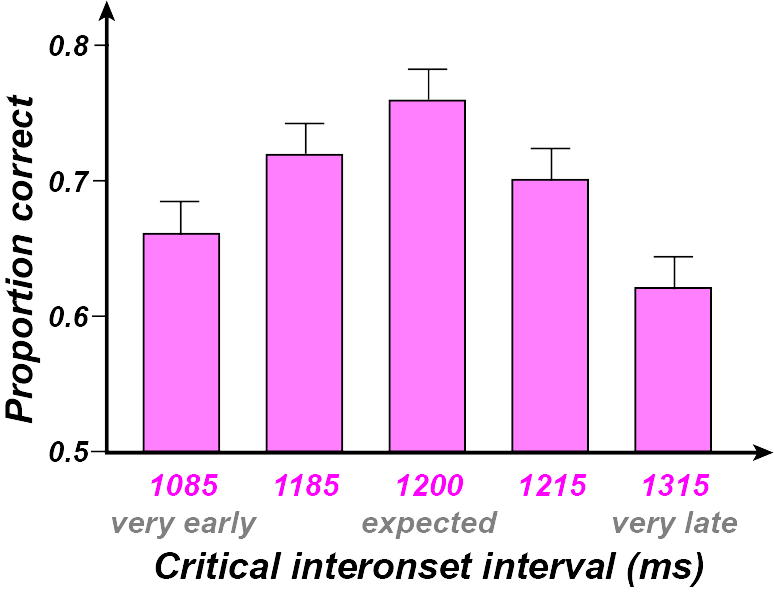

In the Jones et al (2002) experiment, melodies were played with the last note’s onset being varied in time. Performance on a perceptual task was best when the onset of the last note was presented at the precise moment as predicted by the inter-onset interval of the stream of notes before the last note (see figure). The performance on perceptual tasks declined as the onset time of the last (target) note deviated from expected, thus forming an expectancy curve, or a function relating temporal expectedness to perceptual performance. Jones et al (2002) propose a theory of rhythmic entrainment which views attention as an internal rhythmic oscillator with a certain resonance frequency, that adjusts (or entrains) itself to the inter-onset interval of event seqencies.

A diagram of the Jones et al paradigm:

(Adapted from: (Huron, 2006))

Cartoon of results from Jones et al, showing heightened perceptual accuracy at the expected onset time:

(Adapted from: (Huron, 2006))

Rhythmic Expectancy Curve showing optimal perceptual performance when the target note is at the expected downbeat.

(Adapted from: Jones et al, 2002)

A model of rhythmic entrainment

(Adapted from: Jones et al, 2002)

Methods for assessing musical expectancy

How can we measure musical expectancy? The methods adopted to date are many and varied:

- Production Paradigm

- Betting Paradigm

- Probe Tone Paradigm (also in the context of Comparative Ethnomusicology)

- Reaction Time Paradigm

- HeadTurn Paradigm

- Statistical Learning

- Electrophysiological Studies

Production Paradigms

The production paradigm is perhaps the simplest way to demonstrate expectation, in which participants are typically presented with a melody or a chord progression, and are asked to either sing the note they expect to hear next, or play the expected note on a keyboard.

While the production paradigm may seem to be a most direct way to investigate one’s musical expectations, certain issues may introduce bias in results obtained this way. Firstly, many individuals have trouble vocalizing pitches accurately, especially if the intended pitch falls beyond or between the vocal registers of the participant. Production paradigm data collected using a keyboard may be similarly constrained by participants’ keyboard skills. Finally, the production paradigm leads to only one answer, whereas expectation may be divided among several notes.

Betting Paradigm

In contrast to the production paradigm, the betting paradigm (Huron, 2006) eliminates confounds associated with production limitations (such as voice registers and piano skills). In the betting paradigm, participants are given a musical surface such as a keyboard. They listen to a melody and their task is to place bets (chips) on where the melody will end.

The following is a demonstration of the betting paradigm:

Click here for a Max demo of the betting paradigm.

As the above example demonstrates, one advantage of the betting paradigm is that participants’ responses can represent not only what they expect, but also how strongly they expect each note. However, a disadvantage of the betting paradigm is that participants must understand the configuration of the response surface in order to perform the task; thus, in the above example where the keyboard is used, pianists would have an advantage over non-keyboard players.

Probe Tone Paradigm

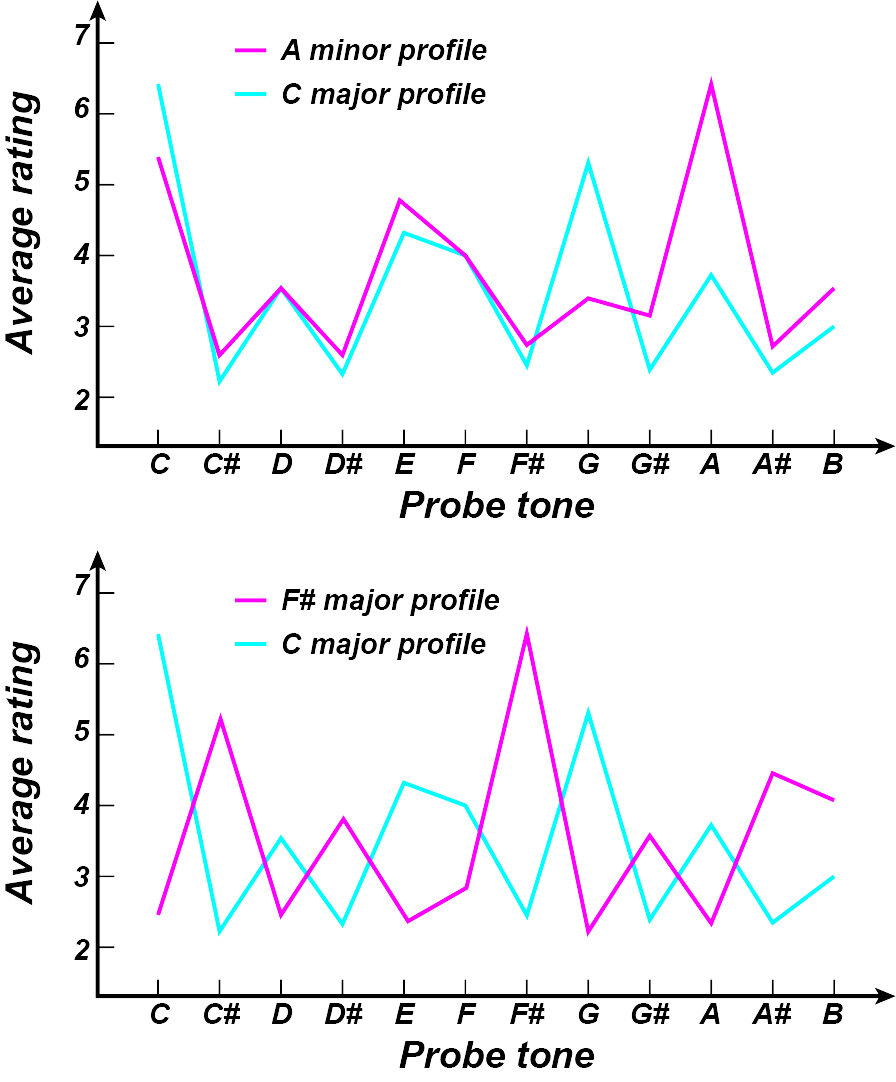

Perhaps the most widely used methodology in music perception cognition, the probe tone paradigm (Krumhansl & Kessler, 1983) measures musical expectancy using goodness-of-fit ratings. In the probe tone paradigm, the participants listen to a melody, which can be a scale, a well-known melody, or an unfamiliar melody. The melody is followed by a tone, and the participant’s task is to rate how well the last tone (called the probe tone) fits with the preceding melody.

Some typical profiles are shown here (see also sections 6 and 7 in Unit 5: Pitch, Intervals and Key Areas):

(image source: (Krumhansl, 1990)

you can have access to all MUTOR interactive maxpatches when you download the MUTOR github repository inside the maxpatches folder.

Notice that when the melodies given to the subjects are in related keys (e.g. C major and a minor scales, as shown in the top panel), the average ratings are highly correlated. In contrast, in response to melodies in unrelated keys such as C major and F# major (bottom panel), the correlations between rating profiles are low, or even negatively correlated.

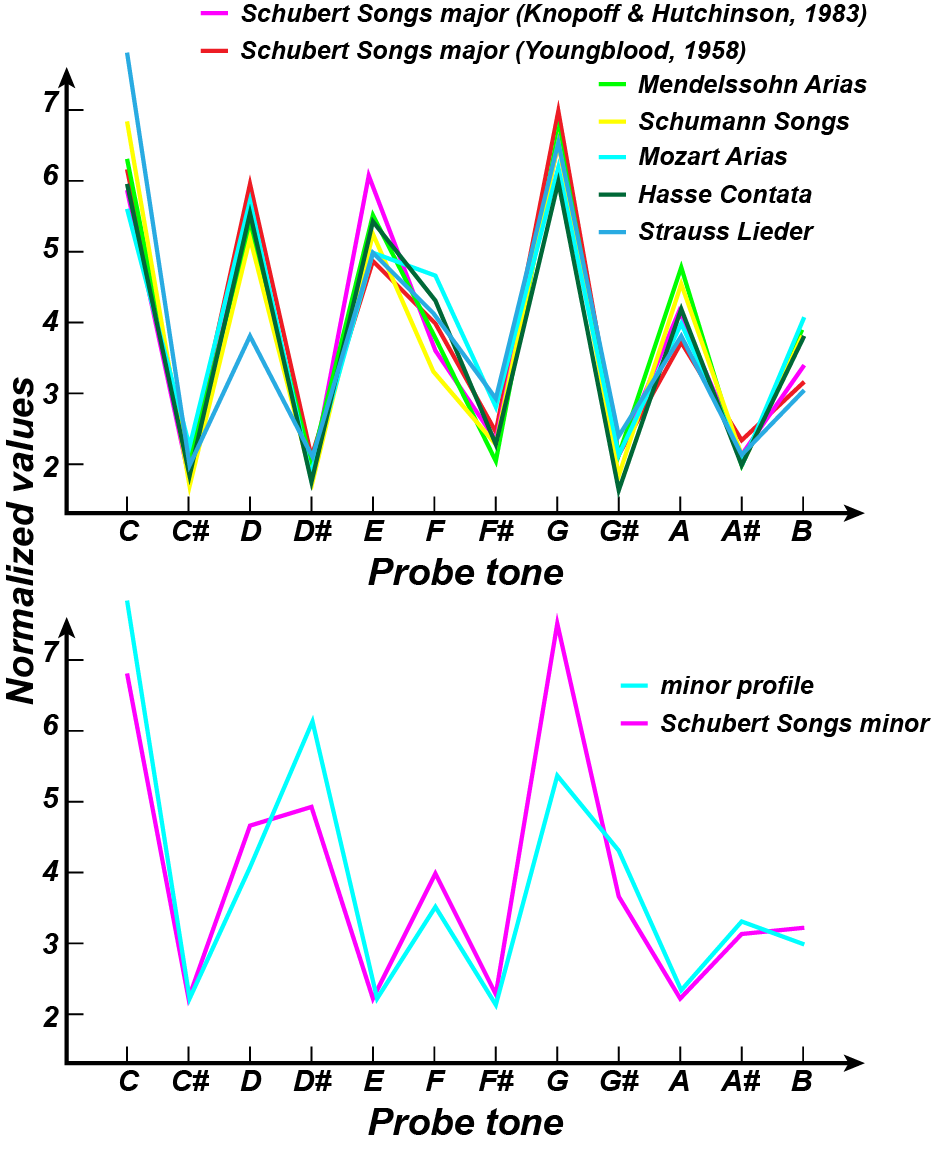

Probe tone profiles obtained for Western music are also shown to reflect the statistics of musical compositions (Krumhansl, 1990).

image source: (Krumhansl, 1990)

Probe tone profiles for major (top) and minor (bottom) keys are highly correlated with the relative frequency at which pitch classes appear in corpuses of classical music.

Comparative Ethnomusicology

To gain a full understanding of musical expectation, it is not enough to only use Western music, A number of music cognition researchers have branched out in the recent years to investiate our expectations for different musical systems of the world. To date, probe tone methdology has been applied to Finnish folk hymns (Eerola, 2003), to North Sami yoiks (Krumhansl et al, 2000), and to the Balinese slendro scale. (Castellano et al, 1984)

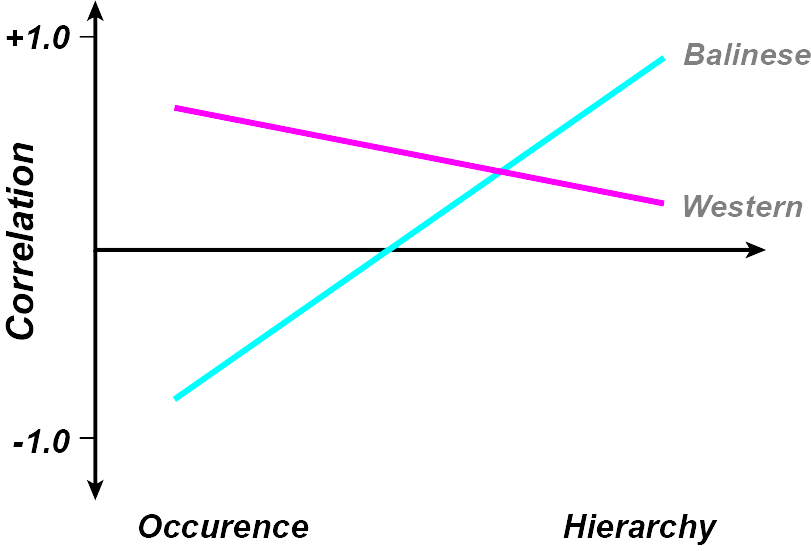

In a study using melodies from the Balinese slendro scale (Castellno et al, 1984), Indonesian and Western subjects Results from probe tone profiles obtained from Balinese music were correlated with tones heard in the Balinese slendro scale. For Indonesian subjects with long-term exposure to Balinese music, correlational strengths reflected a sensitivity to the hierarchy of the scale; i.e. tones that fitted the tonal hierarchy were rated as most fitting, whereas atypical tones in the Balinese scale structure were rated as poorly fitting. In contrast, after listening to Balinese melodies, Westerners demonstrated a significant correlation with the occurrence of the Balinese music; that is, Westerners rated anything they had heard in the Balinese music as being well-fitting.

(image adapted from (Huron, 2006) Results from probe tone profiles obtained from North Indian music.

The ethnomusicologist Simha Arom (Arom, 1991) has investigated rhythm and polyrhythm in Central African music using cognitive principles. His results show that while African music seems to have incredibly complex rhythmic structures, where each member of an ensemble operates at a different metric pattern, these complex polyrhythms could in fact be broken down into simple time ratios such as 2+2+3. These results suggest that expectancy for complex rhythms could also operate on simple cognitive structures.

Reaction Time Paradigm

Another commonly used method to investigate musical expectation, which has been used especially for harmonic expectation, is the reaction time paradigm. The basic tenet of the reaction time methodology is that events which are less expected lead to longer response times.

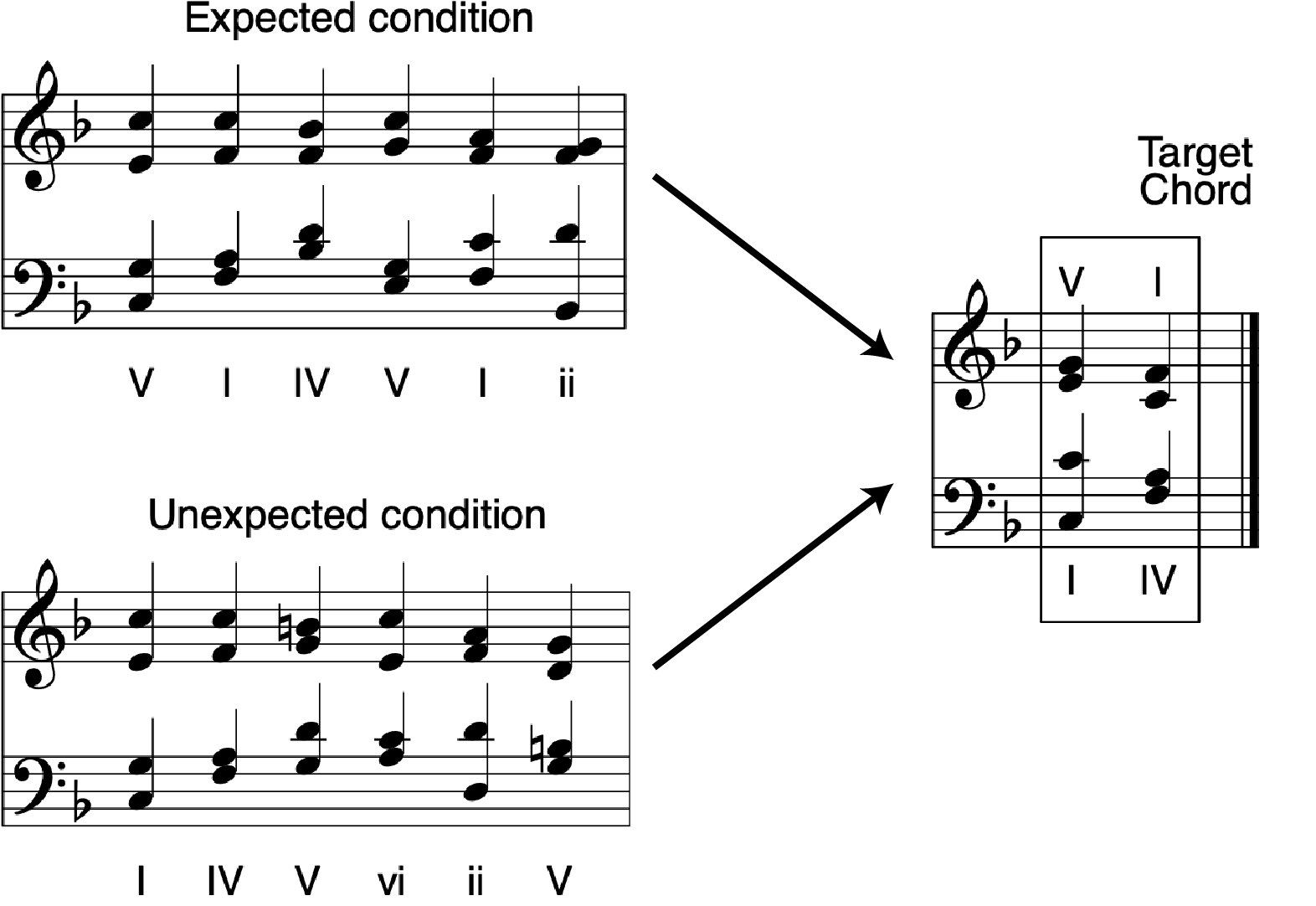

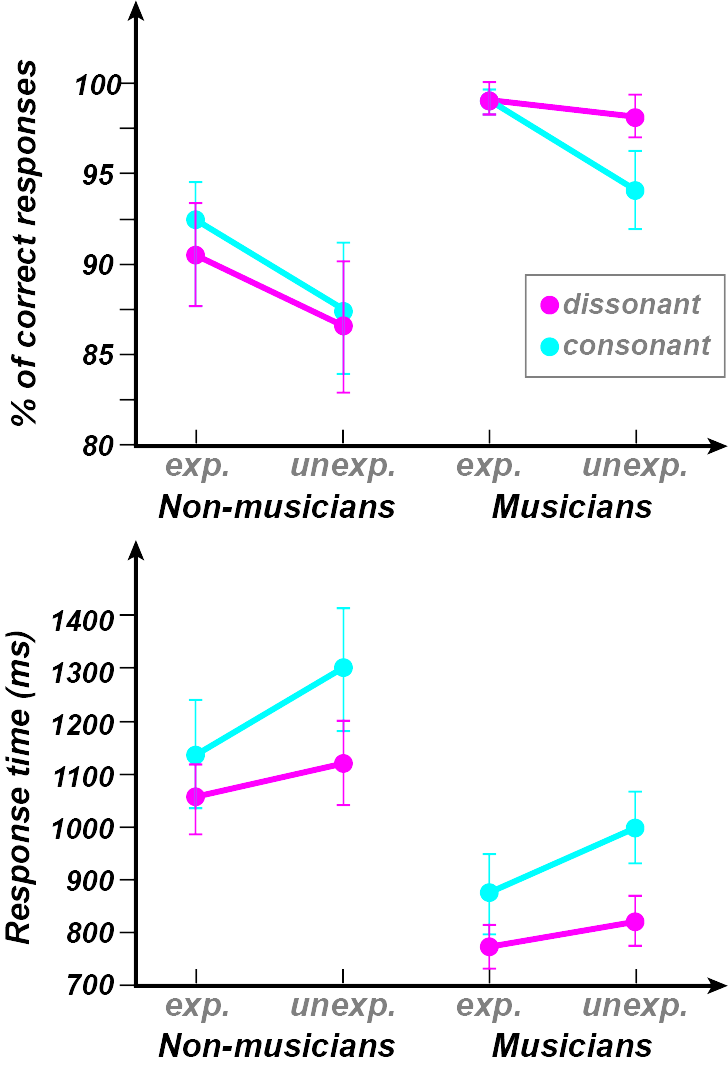

In the standard reaction time experiment looking at harmonic expectancy (e.g. Bharucha & Stoeckig, 1986; Bigand et al, 1999), participants were presented with chord progressions ending with “target” chords. Some of the target chords were harmonically expected whereas others were harmonically unexpected. Half of the target chords were manipulated so that they were either of tune, or dissonant, or slightly temporally asynchronous (i.e. the notes in the chord started slightly unevenly). Participants’ task was to determine whether the target chords were in tune/consonant/temporally synchronous depending on the experiment. Typically, results reveal delayed reaction times and increased error rates for harmonically unexpected target chords. The pattern of results seems similar for musicians and nonmusicians. This methodology is also known as harmonic priming, where the chord progressions prime participants into expecting certain target chords.

(image source: Adapted from Bigand et al, 1999)

Examples of chord progressions with expected and unexpected endings presented to the participants.

(image source: Bigand et al, 1999)

Head Turn Paradigm

Having covered the various methodologies used to empirically observe the effects of musical expectation, one important question concerns where these expectations come from. In an effort to investigate the origins of musical expectations, researchers are also attempting to trace the course of development of these expectations by looking at infants. The problem with infants is that they cannot perform most experimental tasks such as the probe tone paradigm and the reaction time paradigm. Thus one must devise specific experimental procedures for infants to find out what they know.

One commonly used experimental method for infants is the head turn paradigm. The head turn paradigm makes use of the fact that infants tend to turn their heads to look at novel objects, but the look time is significantly reduced for repetitive (boring) objects. For instance, when a light comes on for the first time in an experiment, infants turn to look for an extended time at the light, but after many repetitions of the same light coming on, they look for less time because of their habituation towards repeated events. If the light were to suddenly come on in a different colour, however, infants tend to dishabituate, that is, they tend to look for longer again. One interpretation of these typically results is that infants tend to look longer at unexpected events or objects.

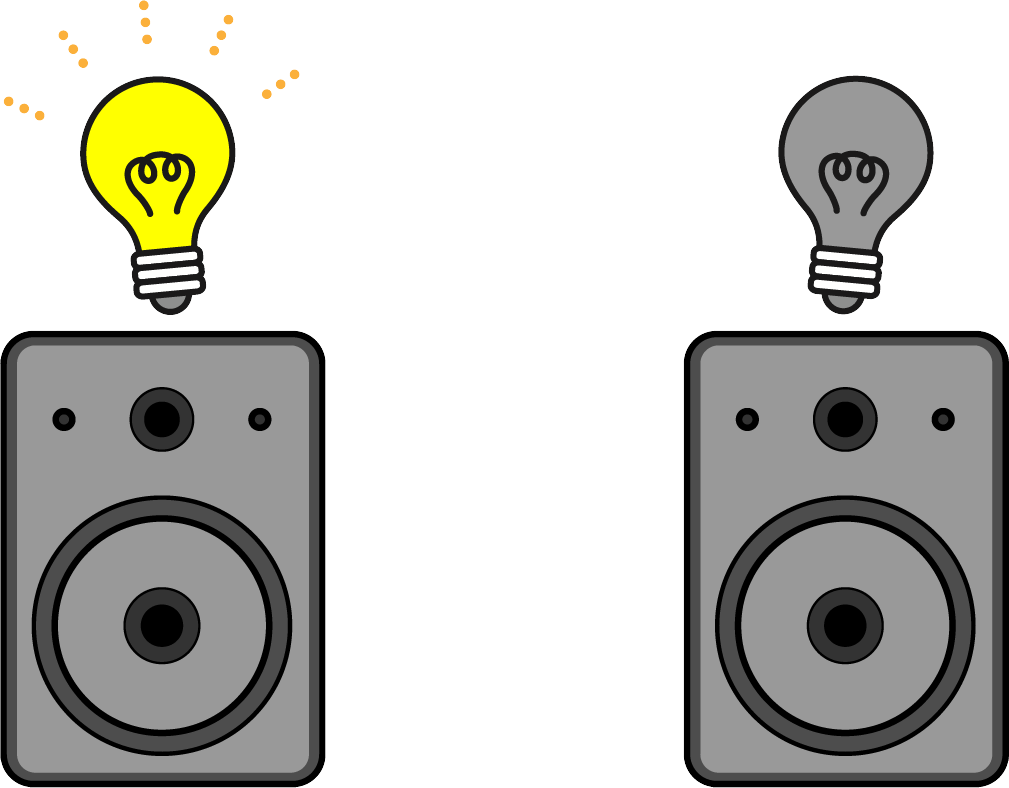

In the head turn paradigm for musical expectation, the light is usually paired with a speaker which plays different musical sounds. In an experiment using groups of musical tones, Saffran et al (1999) paired groups of three tones together with predictable probabilities. For instance, After hearing a stream of tones with these predictable probabilities between them, infants showed a habituation effect towards groups of tones that had been presented with high transitional probability (also see section 8.3 of Unit 8: Gestalt and Melody), but a dishabituation towards tone groups with low transitional probability. These results suggest that infants could learn to expect more probable tone groups.

Example of apparatus for the head turn paradigm. Sounds played from speakers are paired with lights which turn on when the sounds are presented. If the sound has been heard many times before, the infant tends not to turn to look at the light. If the sound is novel, the infant tends to look at the light. Thus amount of time spent looking at the light can be used as an approximation to whether an infant can tell the difference between two sets of sounds.

Saffran’s study on statistical learning of musical expectations

Statistical Learning

From the head turn paradigm, the probe tone paradigm, and comparative ethnomusicological studies, we saw that tones which occur at higher frequencies and probabilities tend to be more highly expected. These are only a few pieces of evidence that statistics play a large role in our formation of musical expectations. We tend to expect things that are more likely to occur, and a sensitivity to these statistics leads to accurate predictions of events that are about to occur.

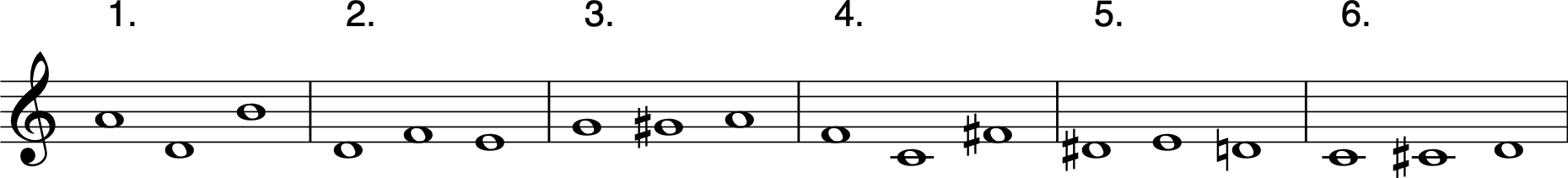

Statistics in music can be calculated at many levels. At the simplest level, event frequencies of notes constitutes a first-order statistic, where the notes occurring most often tend to be most highly expected.

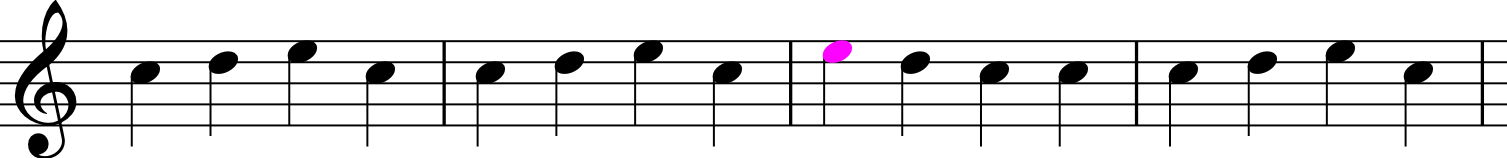

An illustration of first order statistics. Notice that A occurs most frequently in the above passage, B occurs second most frequently, and C occurrs least frequently. Thus:

Freq(A)>Freq(B)>Freq(C).

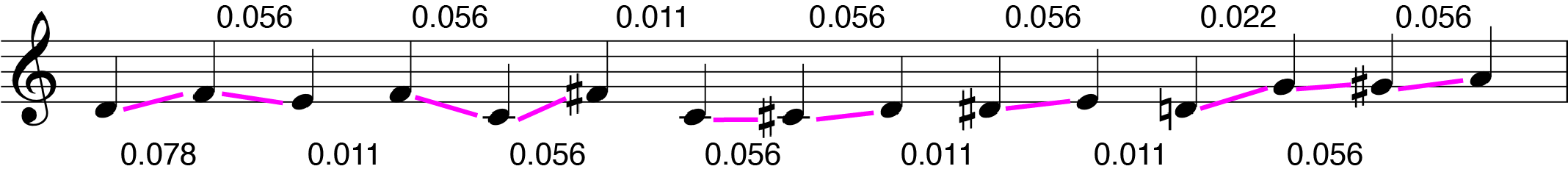

On a higher level, statistics can be observed based on second-order statistics, or the transitional probability of one event given its previous event. Consider the following example:

In this passage, D occurs most frequently before E and after C, except for one instance where D occurs after E and before C. Thus, the frequency of CD as a group is higher than the frequency of ED as a group:

Freq(CD)=Freq(DE)>Freq(ED)

The transitional probability of D given C is defined as:

| P(D | C)=Freq(CD)/Freq(C) |

| By plugging in the formula for transitional probability, we can prove that P(E | D) is higher than P(D | E). |

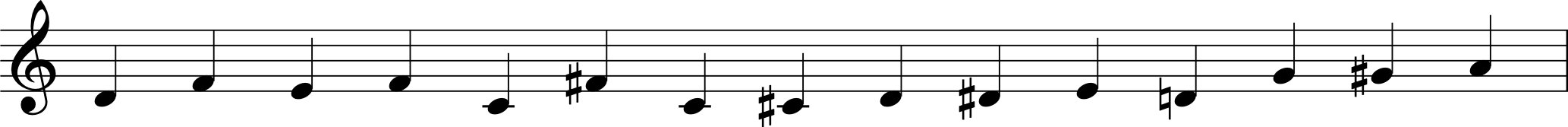

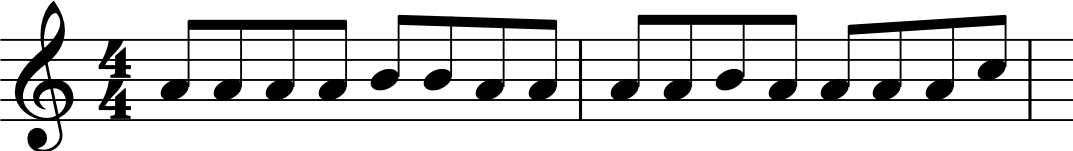

At an even higher level, we can observe higher-order statistics which may not depend on the events themselves, or the events immediately before or after; instead, higher-order statistics may depend on multiple instances many different events apart. In the following example:

The first note in each group (the low G in this case) is predictive of the first note in the next group, regardless of what notes occur in the rest of each group. These non-adjacent dependencies, where one note depends not on its immediate predecessor but on another note many events before it, are important in creating a sense of implied harmony and are useful in voice leading.

Electrophysiological Studies

In the relatively new field of cognitive neuroscience, measures of brain potentials have been used as indices of expectation. Event-Related brain Potentials (ERPs) are time-locked averages of electrical signals recorded from the human scalp. The principle behind ERP technology is that cognitive events, such as the formation of expectations, are due to specific patterns of neural firings. When groups of neurons fire together, they create rapid fluctuations in electrical voltages which can be picked up by electrodes on the surface of the scalp. These electrical fluctuations can be averaged over many instances of the same event, resulting in an electrical signal specifically associated with one cognitive activity.

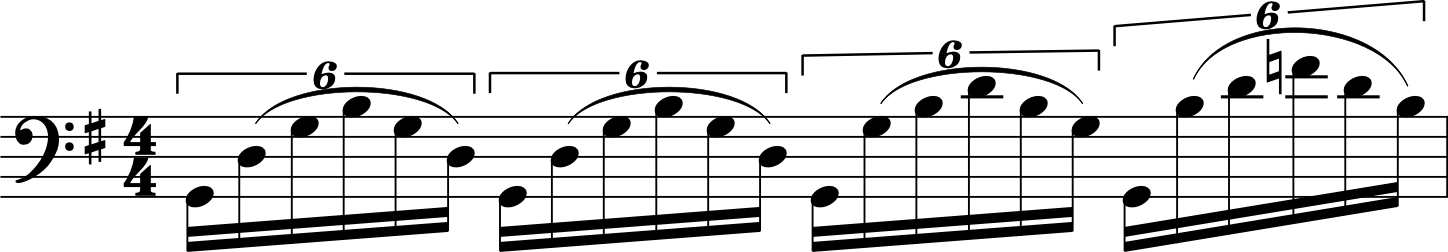

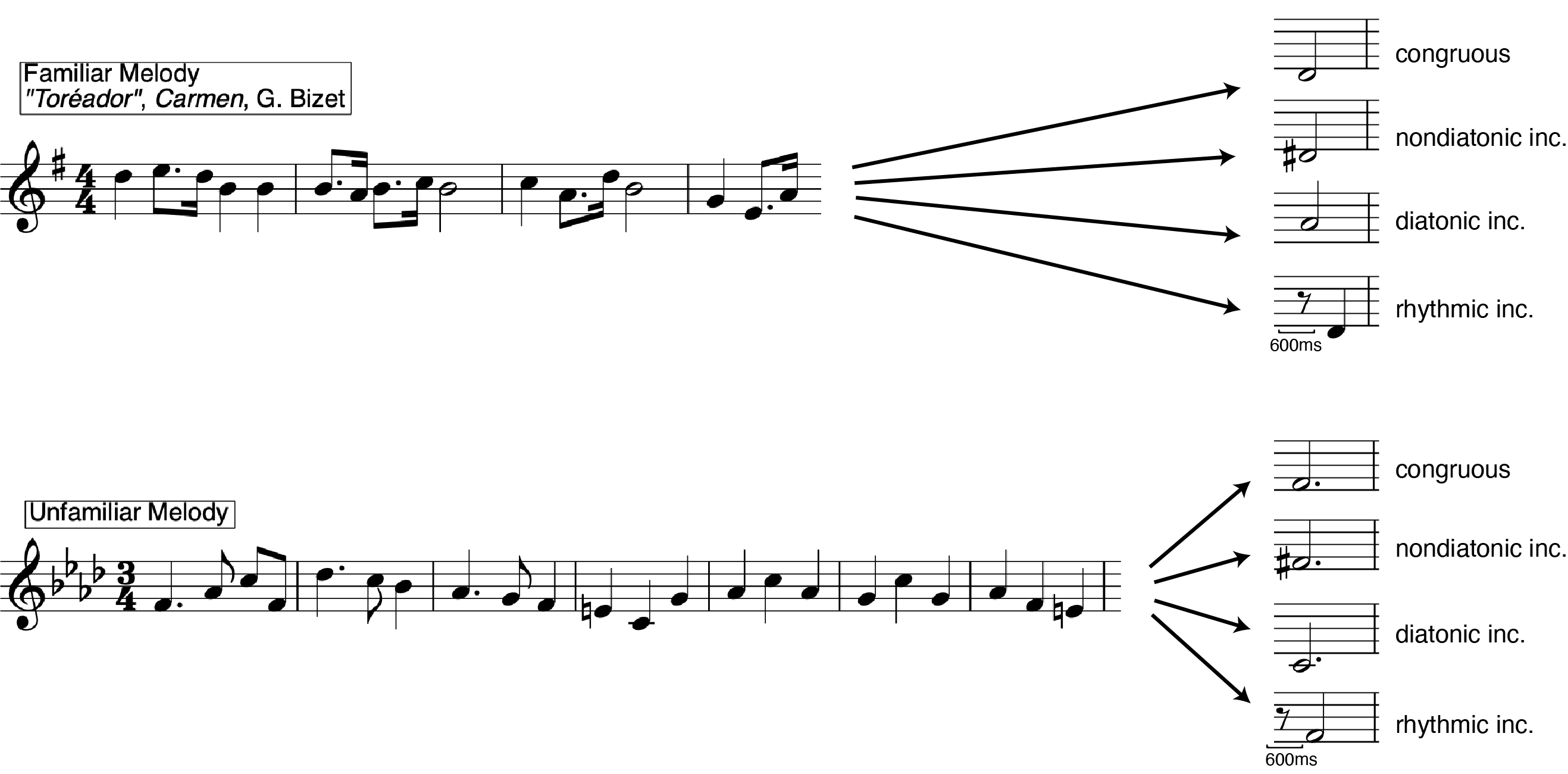

Event-Related Potentials have been used to investigate expectations for melody and harmony. In Besson & Faita’s (1995) experiment investigating melodic expectations, melodies were presented with expected, slightly unexpected, and highly unexpected endings. ERPs showed a positive fluctuation at around 600ms after the onset of the unexpected notes, and the amplitude of this positive fluctuation (termed the Late Positive Component, or LPC) depended on how unexpected the note sounded to the subject. Thus, individuals who were more sensitive to expectations, such as people with musical training, tended to show a stronger effect.

(image source: Adapted from Besson & Faita, 1995)

Examples of Besson & Faita’s (1995) stimuli. Melodies were presented with expected, slightly unexpected, and highly unexpected endings.

(image source: Besson & Faita, 1995)

ERP results from Besson & Faita (1995). Negative potential is plotted upwards by convention. Notice a positve difference between ERPs for unexpected (incongruous = highly unexpected; diatonic = slightly unexpected) and expected (congruous) notes. This difference, named the Late Positive Complex (LPC), is largest parietally around 600ms after the onset of the note and is larger for musicians.

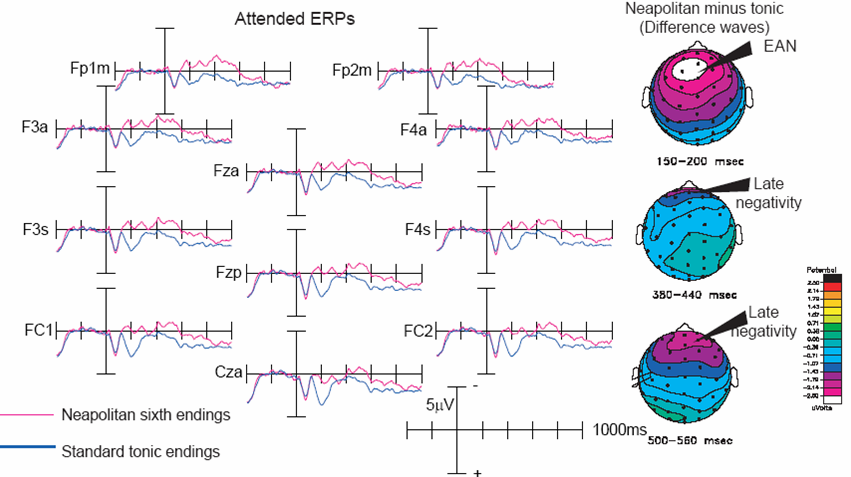

Event-Related Potentials have also been used to investigate expectation for harmony. When chord progressions with expected and unexpected endings were played to subjects, the unexpected chords elicited two negative ERP components. The first negative component occurred around 150ms after the onset of the unexpected chord, whereas the second one was largest around 500ms after the unexpected chord.

The earlier of the two components has been coined Early Right Anterior Negativity (ERAN) by Koelsch et al (2000) because the effect was originally observed as a negative waveform largest around the right anterior area of the human scalp. Similar effects were subsequently named EAN (Early Anterior Negativity) (Loui et al, 2005) because they were mostly observed bilaterally instead of right-sided in other studies. The later component was coined N5 (Negativity at 500ms) by Koelsch et al (2000) and LN (Late Negativity) by Loui et al (2005).

(image source: Loui et al, 2005)

ERPs elicited by expected and unexpected chords. Negative is plotted up. Notice that the ERPs for the two kinds of chords diverge at two time points, first around 150-250ms, and then again at 400-600ms. Both effects are negative for the unexpected chords. The earlier effect is largest bilaterally over frontal areas of the brain; the later effect is largest over prefrontal areas.

Summary

Expectation and anticipation are important and evolutionarily advantageous characteristics of our cognitive system. In music, expectations feature prominently in our perception of melody, harmony, and rhythm. The systematic violation of expectation seems to lead to arousal and affect in our musical experience. The Implication Realization Model and Gap Fill are rather precise models that can be used to predict what is or is not expected in musical melodies, whereas the Dynamic Attention Theory is an account for our expectancies for rhythm.

Musical expectancies have been observed using many convergent methods. These methods include production, betting paradigm, probe tone ratings, comparative ethnomusicology, reaction time methodology, the head turn paradigm, and Event-Related Potentials. Statistics in music seem to play an important role in musical composition, where we generally expect musical events that occur with high frequencies and transitional probabilities in a musical style.

Quiz

Why might it be evolutionarily advantageous for our brains to form expectations? Give a real-life example. Are there any circumstances under which it can be a disadvantage to form expectations? If so, what are these circumstances?

What is the gap fill principle? Give an example of gap fill in a melody.

Describe the probe tone paradigm. What do probe tone profiles look like?

What are event-related potentials and what do they show for unexpected musical chords?

What kinds of statistics are used in musical compositions?

References

- Huron, D. “Sweet Anticipation”. MIT Press. 2006.

- Krumhansl, C.L. & Kessler, E.J. “Tracing the dynamic changes in perceived tonal organization in a spatial representation of musical keys”. Psychological Review, 89(4): 334-368. 1982.

- Krumhansl, C.L. “Music Psychology and Music Theory: Problems and Prospects”. Music Theory Spectrum, 17(1): 53-57, 78-80. 1995.

- Castellano, M.A. & Bharucha, J.J. & Krumhansl, C.L. “Tonal hierarchies in the music of North India”. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113(3): 394–412. 1984.

- Arom, S. “African polyphony and polyrhythm: musical structure and methodology”. Cambridge University Press. 1991.

- Krumhansl, C.L. “Cognitive Foundations of Musical Pitch”. Oxford University Press. 1990.

Authors

Topics

- Unit10Introduction

- What is expectancy

- Why study expectancy

- Theories of expectation

- Expectancies for Melody

- Expectancies for Rhythm

- Methods for studying expectancy

- Summary

- References

- Links and Downloads

- QuizItems