Unit 2: The Auditory System

Synopsis

The auditory system is a complex collection of organs that transfer sound from pressure waves in the air around us into electric signals that are ultimately processed by the brain. The auditory system can be thought of as consisting of two parts: the ear, itself made up of the outer, middle, and inner sections, and the central nervous system, which includes various structures in the brain and the spinal cord that enable hearing. The different organs that comprise the auditory system play different roles in providing us with information about our sonic environment. The cochlea, for example, a fluid-filled spiral-shaped organ that contains the basilar membrane, is primarily responsible for sensing frequency, the physical correlate of our perception of pitch. In addition to the operation of each ear as a separate organ, the brain is able to integrate information from the two in order to form accurate judgements about the position of sound sources in space.

- How do we hear?

- The auditory pathway (ear & brain)

- Structure vs Function

- The Ear

- Middle Ear

- Inner Ear

- Cochlea

- Tonotopic Mapping

- Brainstem Pathways

- Amplitude Modulation

- The Active Ear

- Evolution Of The Auditory System

- Music in Other Species

- Hearing Damage

- How do you know when you have damaged hearing?

- Types of Hearing Loss

- Summary

- Quiz

- References

How do we hear?

Much of our auditory and musical functions arise from the anatomical structures of our brain and auditory system. To understand the physiological bases of musical phenomena, this unit will provide an in-depth overview of the structure and function of the auditory system.

The auditory system is a set of biological structures and functions that enable you to hear. To understand this system, we will follow the pathway that sound travels from the outer ear to the cochlea. We will discuss how the cochlea transforms sound into neural impulses, which are then to be relayed in various transformations through the neural centers of the brainstem and midbrain before it is processed by the primary and secondary auditory cortices.

In addition to feedforward pathways from the auditory periphery to the cerebral cortex (also known as afferent pathways), we will also consider efferent pathways, or feedback routes from the central nervous system to the auditory periphery, which support the view that hearing is not a passive state, but an activity that requires constant change and flexibility.

To get a sense of the evolution of the auditory system, we will also compare the human auditory system with that of other animals, noting the commonalities and divergence points of the structures involved in hearing.

Finally we look at when the auditory system malfunctions. Types of hearing loss and their origins will be discussed. We will consider the importance of hearing protection, and explore various ways to protect your ears.

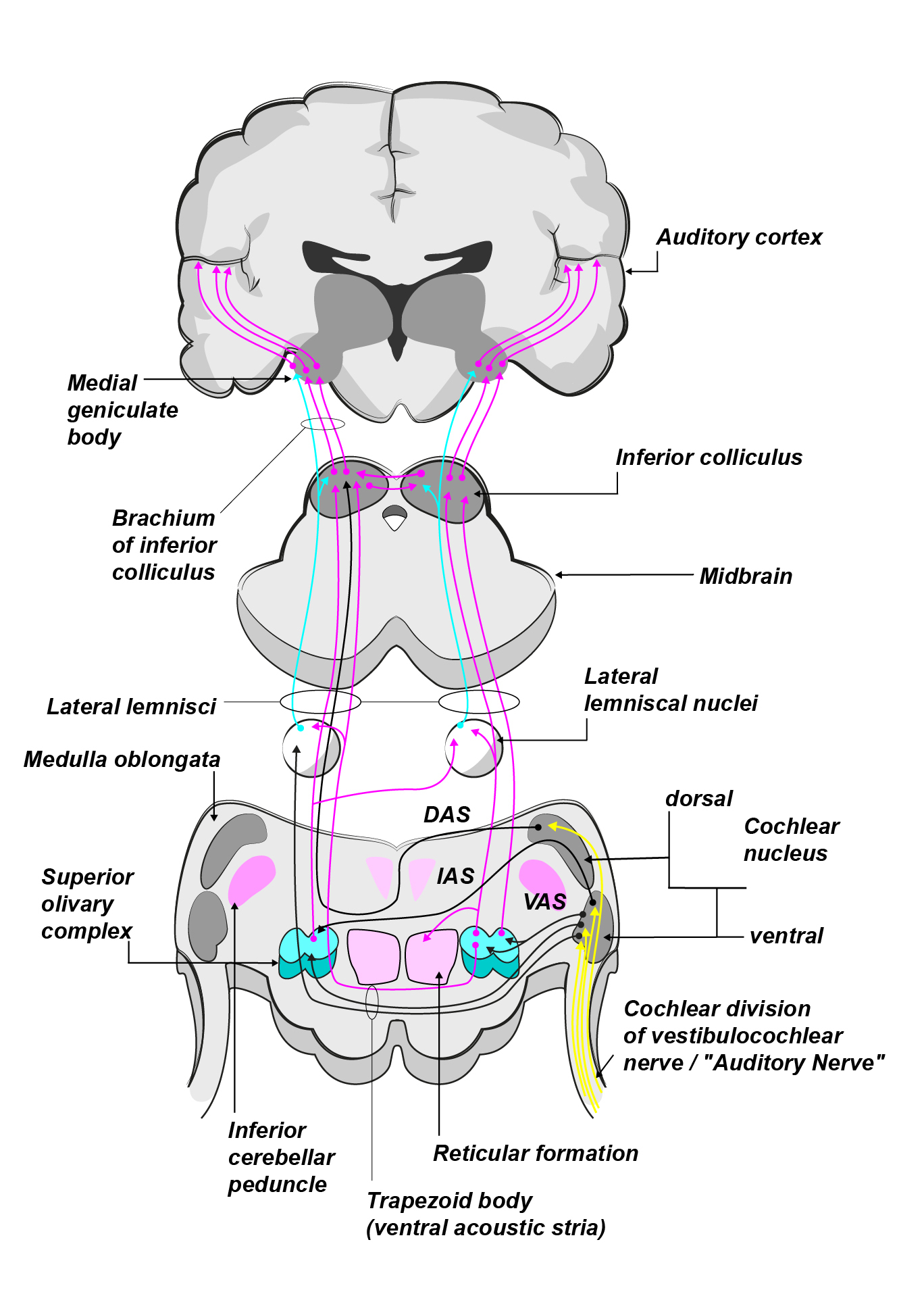

The auditory pathway (ear & brain)

The anatomy section of this unit will cover the peripheral and central auditory nervous systems, from the outer ear all the way up to the secondary auditory cortex. The auditory periphery includes various parts of the ear and ends at the auditory nerve, which leades from the cochlea to the brainstem. The central nervous system includes the brain and the spinal cord, with parts of the central nervous system involved in auditory function being in the brainstem, the midbrain, and the cerebral cortex. Afferent pathways include all neural pathways going from the auditory periphery to the cerebral cortex, whereas efferent pathways are all pathways coming from the cortex back to the periphery. Both pathways will be discussed in the present unit. Emphasis will be placed on the function as well as structure of each region along the auditory pathway.

(Image by Janina Luckow)

Structure vs Function

A detailed look at each anatomical region of the auditory system must include both the structure and the function of each region. Many regions along the auditory pathway serve specific functions, and some aspects of their structure have evolved especially to optimize these functions. Two of the main auditory function we will discuss are Tonotopic Mapping and Binaural Hearing. While both are important functions of the auditory system as a whole, specialized mechanisms are built into the Cochlea and the Superior Olive to enable Tonotopic Mapping and Binaural Hearing respectively. we will see how the structure of each part of the anatomy is optimized to perform its function.

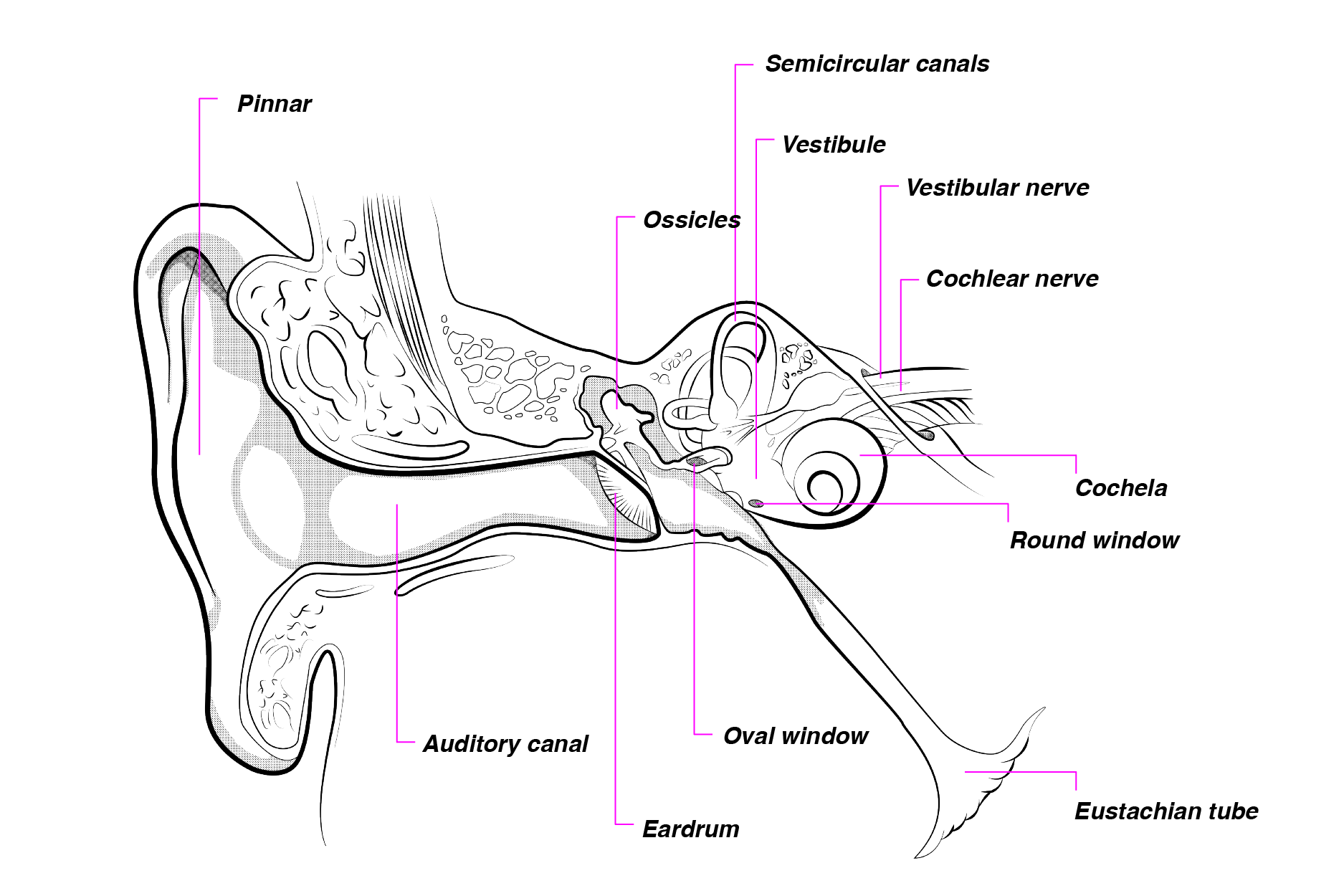

The Ear

“The ear”, for our purposes, is not just what sticks out on each side of your head. Although the visible part of the ear, also known as the pinna, constitutes the outer ear and plays an important role in hearing, The ear also includes the middle, and inner ear, each of which has structures specialized for their functions. The middle ear has a series of ossicles, or tiny bones which conduct and amplify the sound signal. The inner ear is of vital importance to hearing as it includes the Cochlea, perhaps the most important structure in the auditory periphery, which transduces sound signals into nerve impulses.

(Image by Janina Luckow. Adapted from: Rossing et al, 2001)

The outer ear includes the pinna, the visible portion of the ear coming out of the sides of the head. The pinna directs sound into the ear in a funnel-like manner, and the bony ridges of the pinna play an important role in sound localization. Sound waves approaching from the environment bounce off the bony ridges of the pinna such that the higher frequencies reflect off the bony ridges whereas the lower frequencies bend around the pinna. Using the information of how sounds are reflected along the pinna, localization of different frequencies is possible.

The shape of the ear, as well as the head and shoulders, give rise to the Head Related Transfer Function (HRTF), a function which relates sound pressure level (dB) to frequency. The HRTF is unique for each individual but may be simulated (to some level of precision) by a dummy head. Recordings sometimes use microphones fitted to a dummy head so as to get a precise signal which takes into account some of the variability explained by the shape of the pinna, head and shoulders.

In addition to the pinna, the outer ear includes the auditory canal and the ear drum. The auditory canal funnels sound from the pinna to the rest of the ear; it should be cleaned periodically as it is sometimes the site of earwax buildup which may be detrimental to hearing. The ear drum, also known as the tympanic membrane, receives vibrations of sound waves from the auditory canal, and sends vibrations through the rest of the ear. The tympanic membrane demarcates the outer ear from the middle ear.

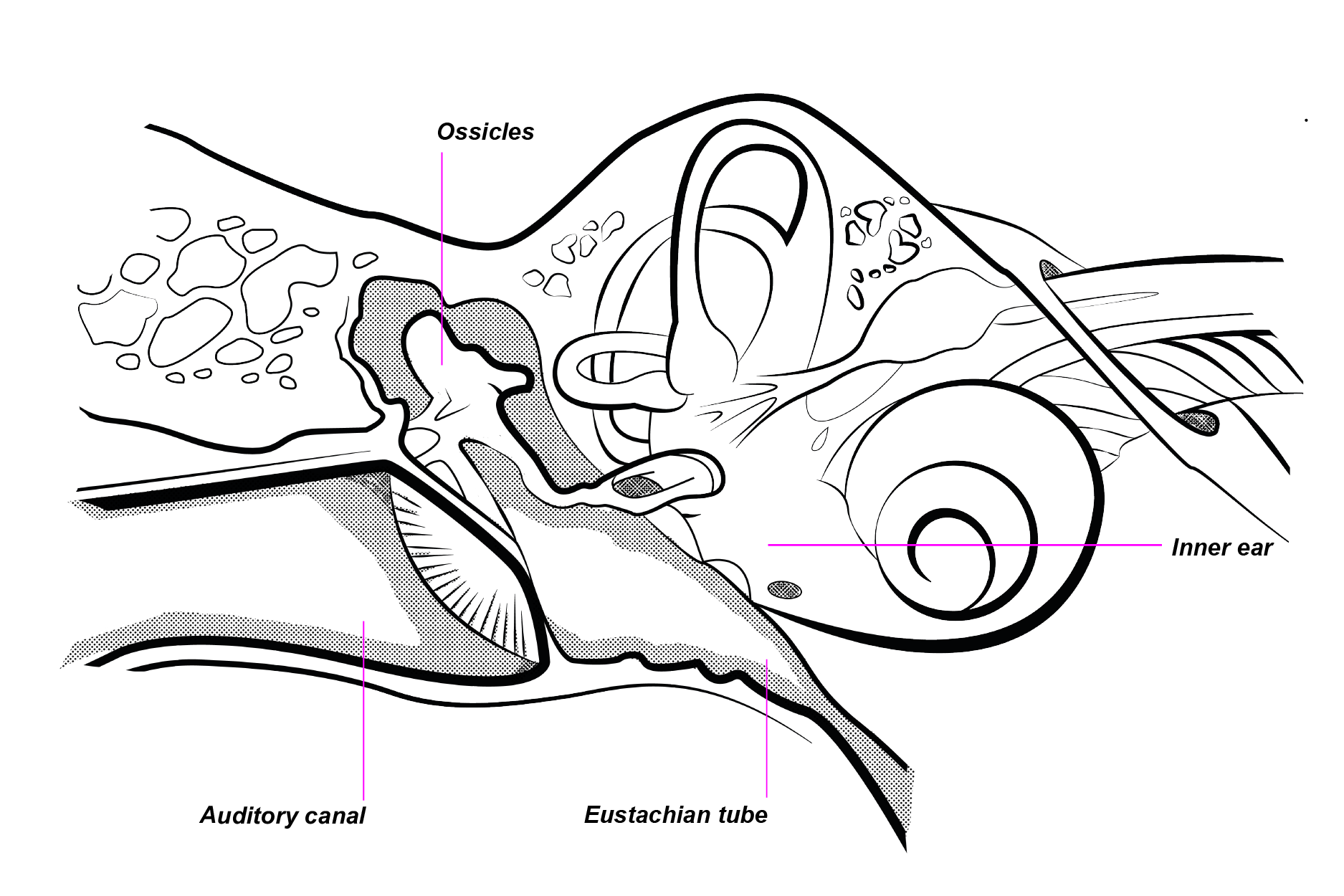

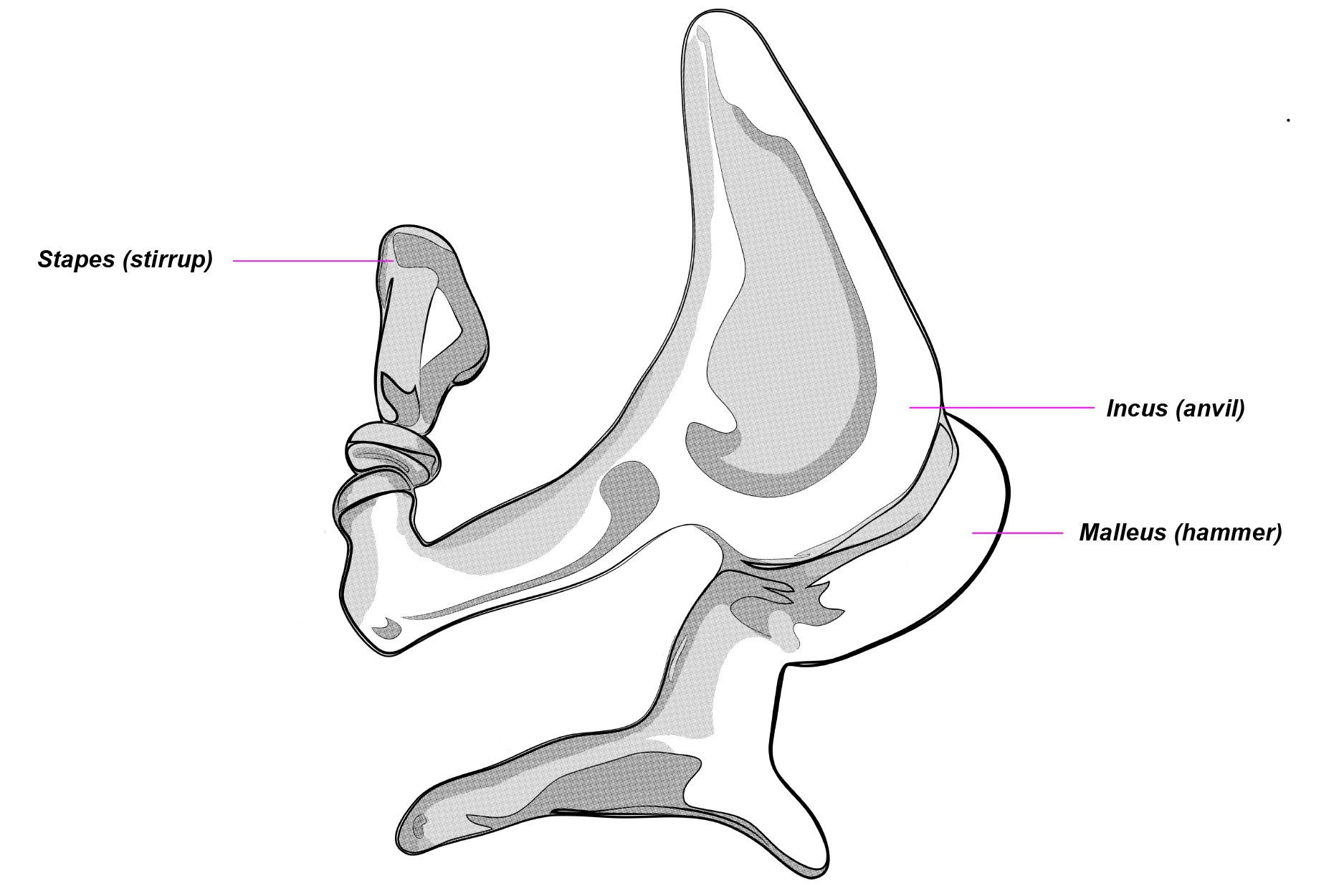

Middle Ear

The middle ear is a cavity between the tympanic membrane and the oval window of the cochlea. The middle ear consists of middle ear bones and the Eustachean tube.

(Image by Janina Luckow. Adapted from: HyperPhysics) Middle ear bones, or ossicles, include the incus, malleus, and stapes. These ossicles vibrate as they receive sound vibrations from the tympanic membrane. One of the ossicles, the stapes, is attached to the oval window of the cochlea in the inner ear; thus the vibrations of the stapes is received by the cochlea.

(Image by Janina Luckow)

The Eustachean tube is a fluid-filled tube that connects the middle ear to the pharynx (the back of the nose and throat). Its function is to adjust air pressure in the auditory system. When confronted with changes in air pressure, the Eustachean tube opens briefly to let air pressure equalize on either sides of the tube. It can also be opened voluntarily by yawning or opening one’s mouth, as is often experienced during rapid air pressure changes in an airplane. The Eustachean tube also directs mucus away from the middle ear, and is occasionally the site of ear infections due to bacterial growth in the mucus lining of the tube.

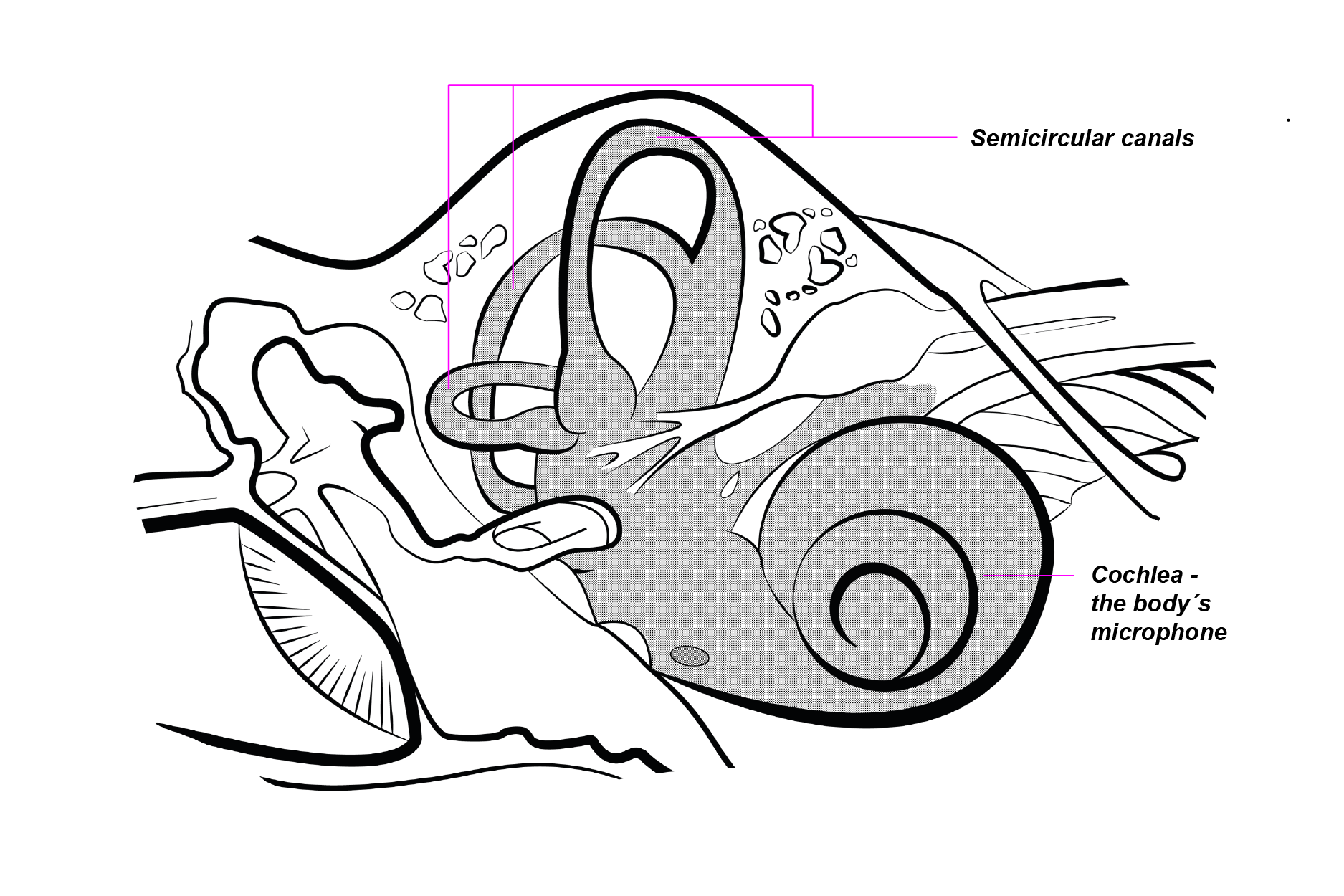

Inner Ear

(Image by Janina Luckow. Adapted from: HyperPhysics)

The inner ear is the region between the oval window and the auditory nerve. It consists of the semicircular canals and the cochlea, which includes various structures. The auditory nerve leads out of the cochlea and into the brainstem.

The semicircular canals are fluid-filled structures that provide us with a sense of balance. They are part of the vestibular system, which provides us with the sense movement and position in space. The structure of the semicircular canals, with three perpendicular channels, helps detect movement of the head in three dimensions, such that a sense of balance can be maintained.

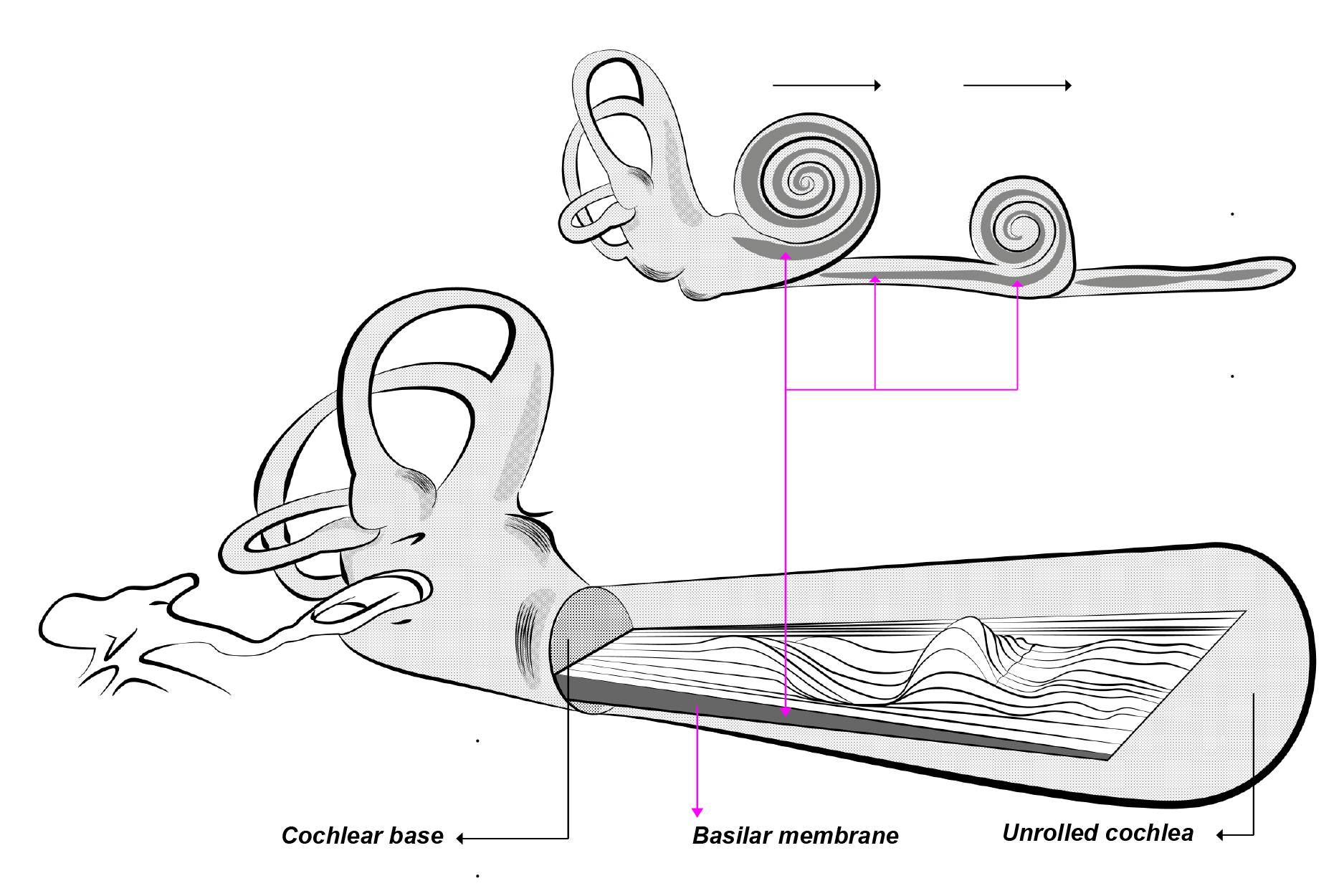

The cochlea, often referred to as the “hearing organ”, is most important to the auditory system in that it is responsible for converting the sound signal into nerve impulses to be processed by the rest of the auditory system. It is a fluid-filled, snail-like coiled structure which contains several chambers divided by membranes. It is the relative vibrations of these membranes along the cochlea that enable the transmission of different sound frequencies.

Cochlea

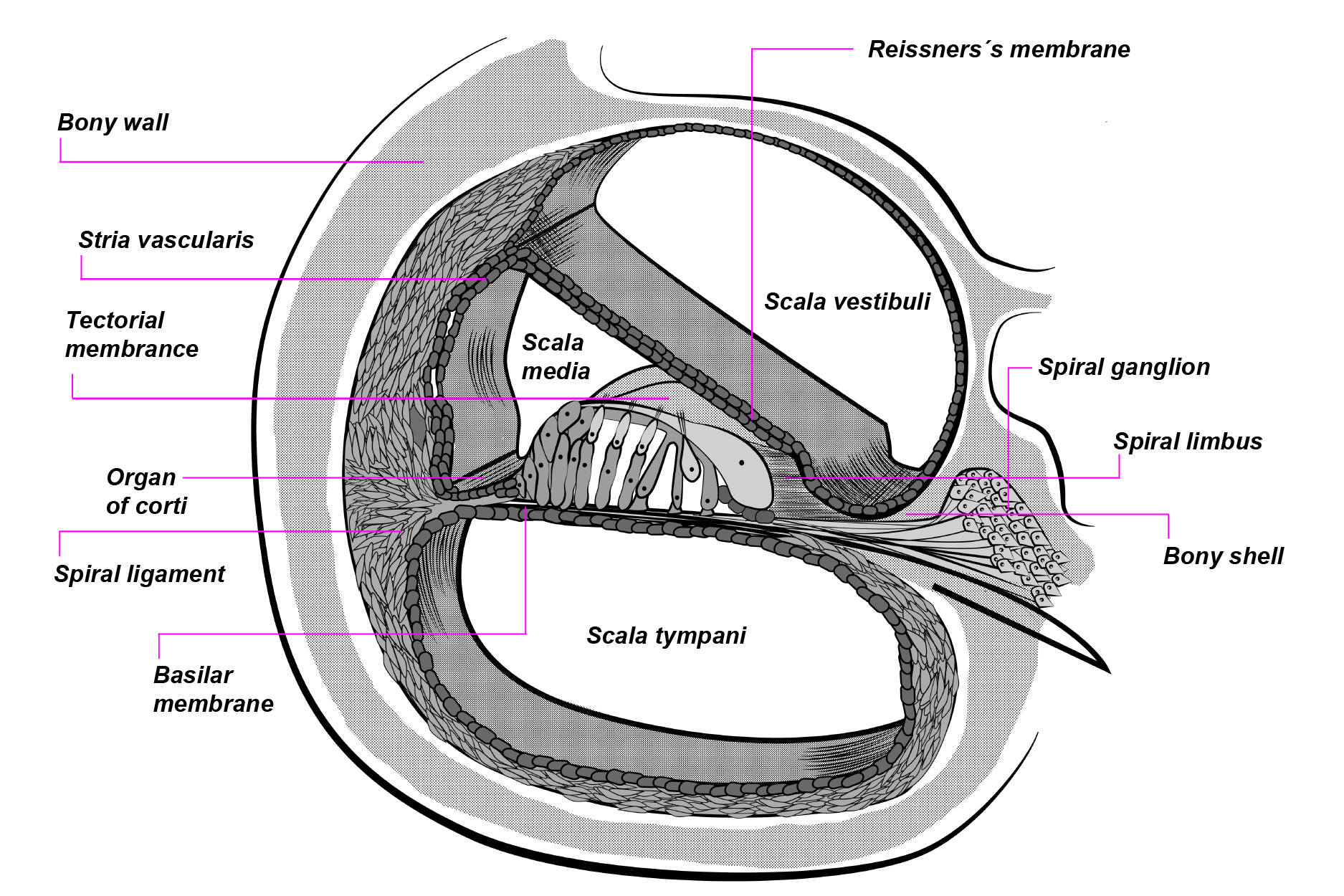

The cochlea is a coiled, fluid-filled tubular structure. It is lined with membranes which divide the inside of the cochlea into fluid-filled compartments.

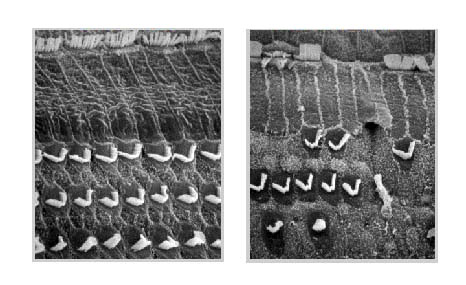

(Image source: Rebillard, M. L., Journey into the World of Hearing by Pujol, R. et al., NeurOreille, Montpellier. Licensed by copyright owner)

A dissected cochlea of a human fetus.

(Image by Janina Luckow)

A cross-sectional view of the cochlea shows that it is divided by the Reissner membrane, the tectorial membrane, and the basilar membrane.

Cross-section view of one turn of the cochlea.

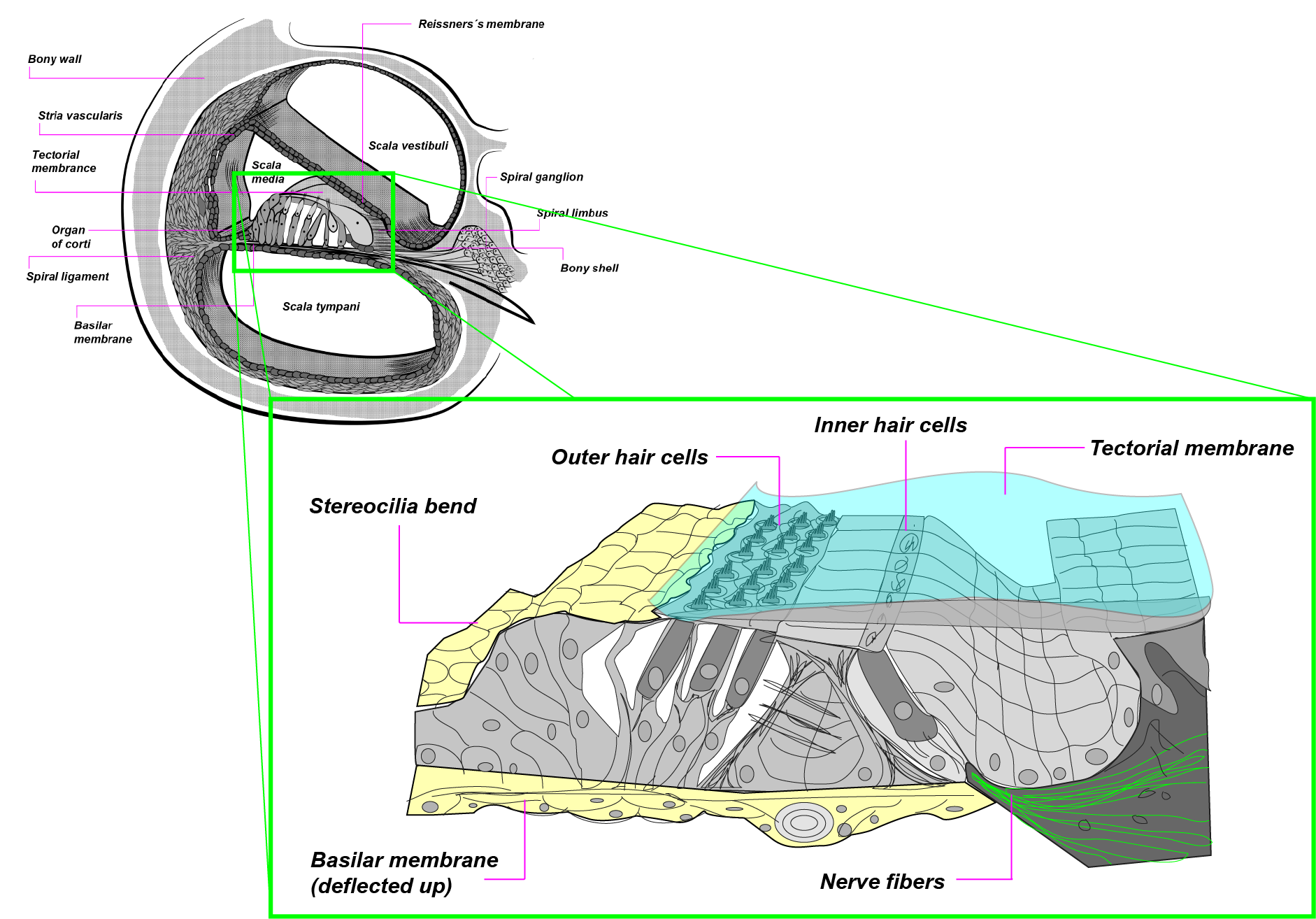

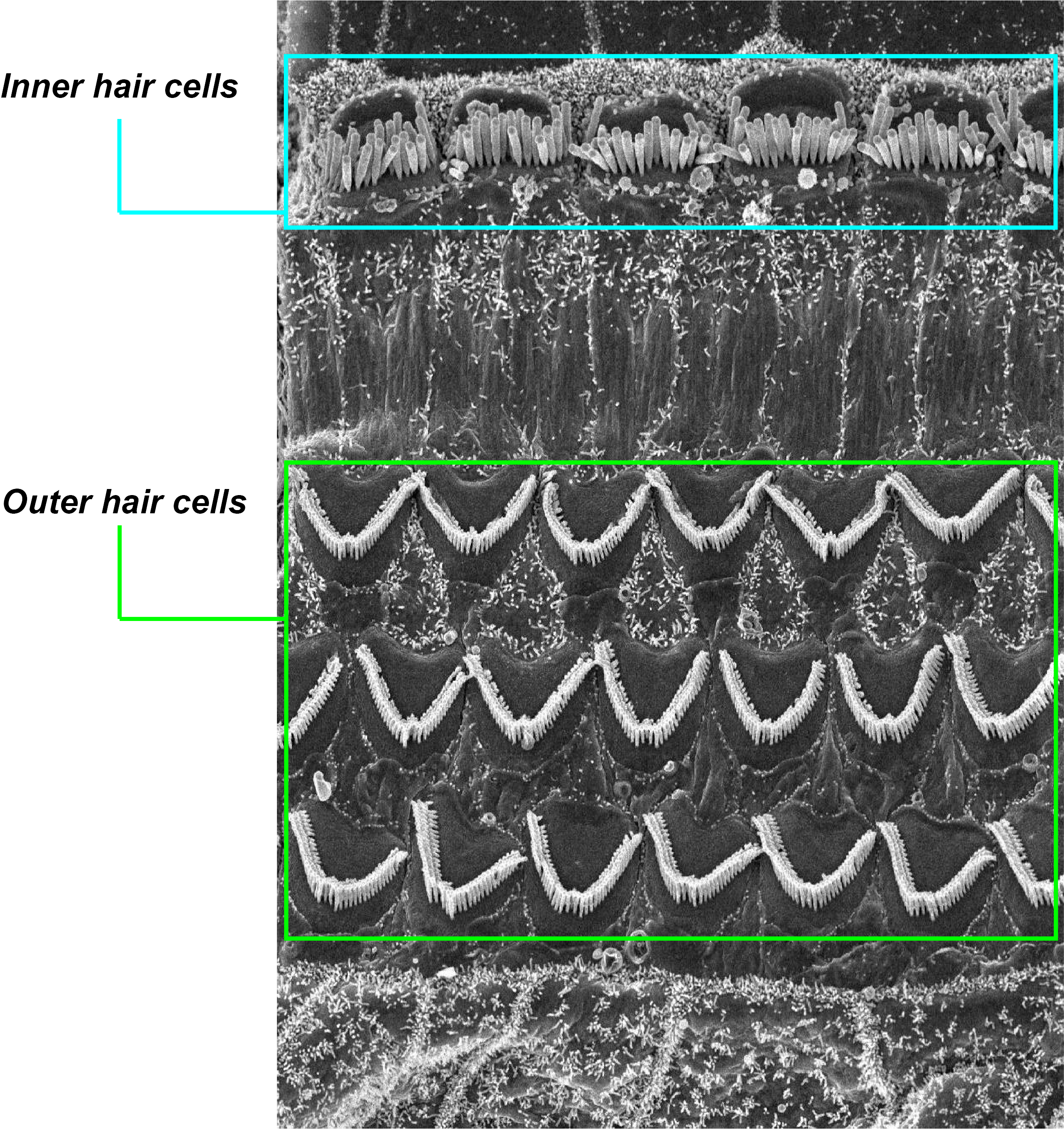

These membranes together divide the cochlea into its fluid-filled chambers: scala vestibuli, scala tympani, and scala media. Importantly, the middle section contains the Organ of Corti, which includes the basilar membrane, the tectorial membrane, and the hair cells between these two membranes.

Organ of Corti

Magnified diagram of the Organ of Corti, showing the basilar membrane, inner and outer hair cells, tectorial membrane, and auditory nerve fibers.

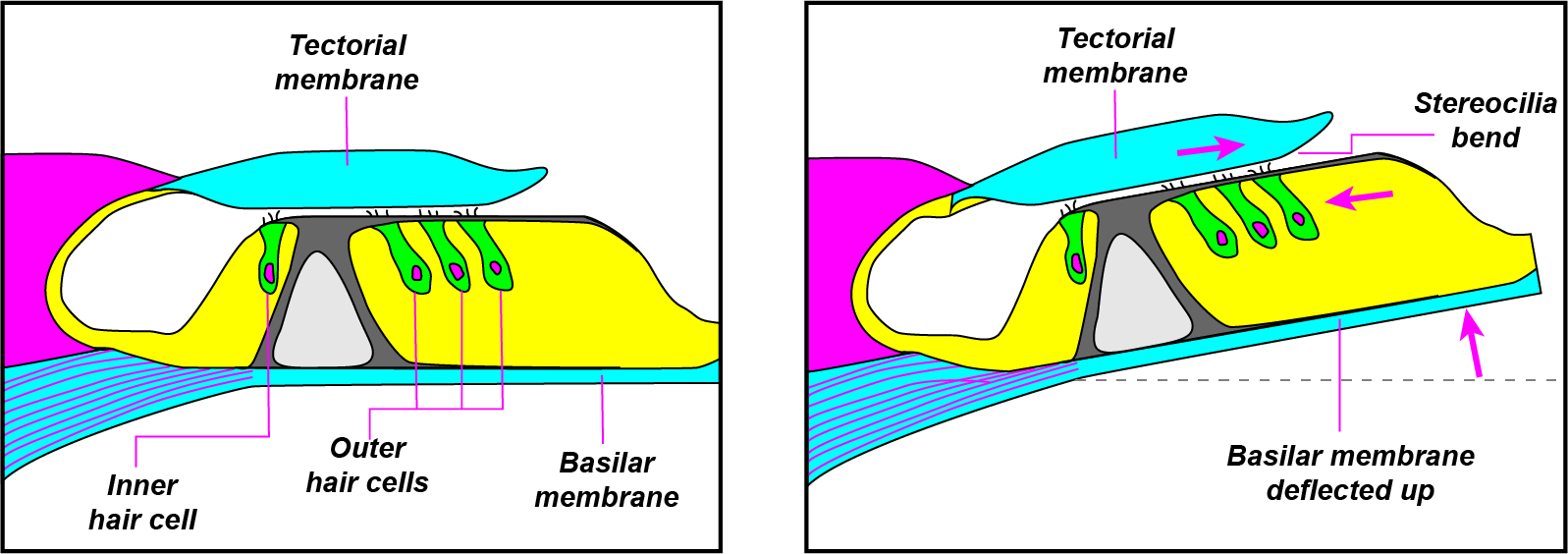

When the cochlea is excited by sound coming in, vibrations are sent through the fluid-filled chambers, thus causing movement in the membranes in the Organ of Corti. The movements of the tectorial membrane excite the inner hair cells on the surface of the basilar membrane, thus causing the hair cells to open their channels and send nerve impulses on to the fibers of the auditory nerve.

(Image by James Cheung)

(Image by James Cheung)

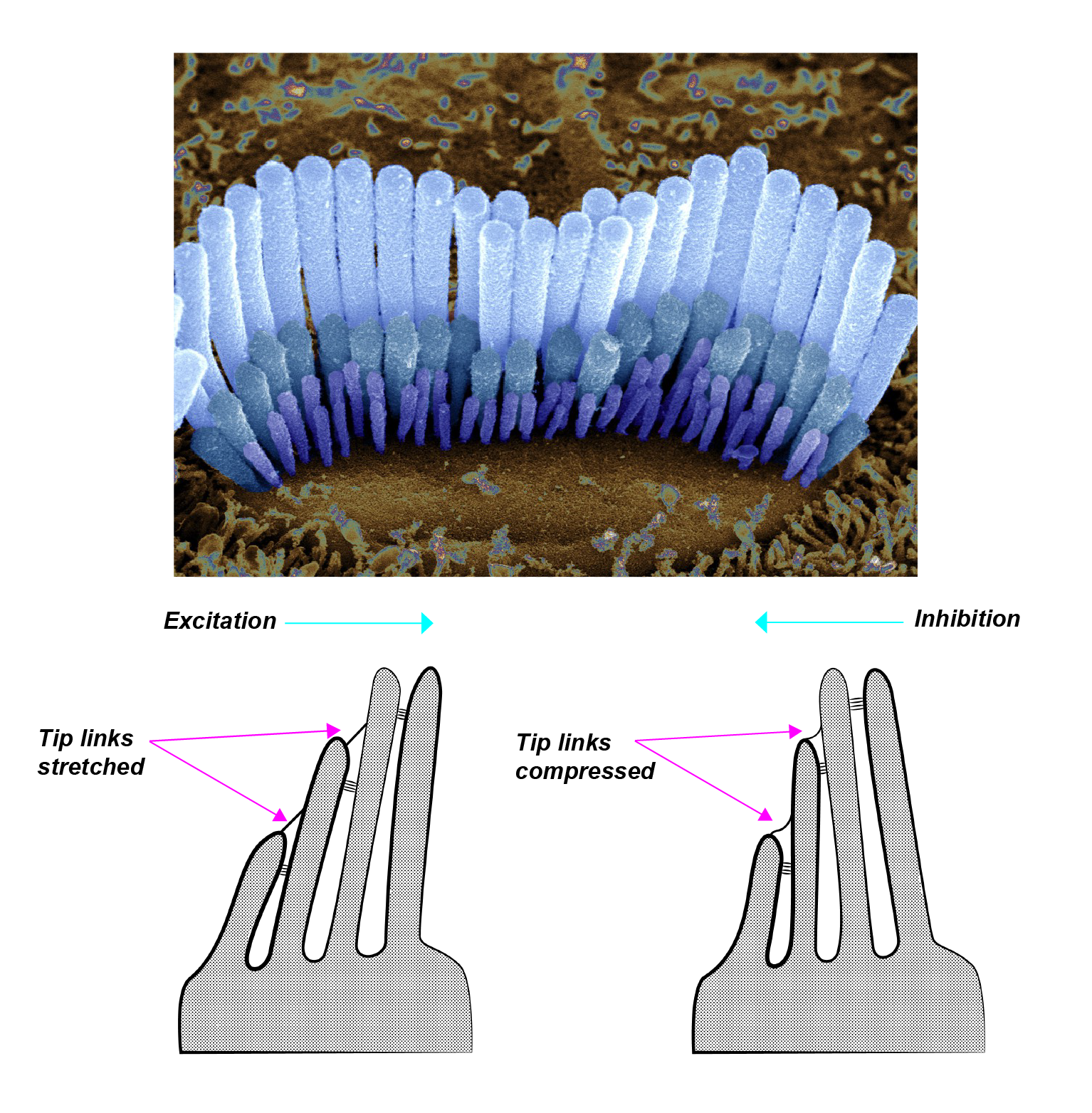

In its resting state, the basilar and tectorial membranes are parallel, the stereocilia (tiny hairs on the surface of the inner and outer hair cells) are relaxed and close together, and the ion channels between the stereocilia are closed. When sound excites the cochlea, its vibrations are sent down the fluid of the cochlea so that the basilar membrane is deflected. When the basilar membrane moves, the inner hair cells in the basilar membrane change shape, and the stereocilia on the inner hair cells are stretched, thus opening up the ion channels in the inner hair cells and causing a chemical transduction to occur within the cells. The chemical transduction of the inner hair cells results in the generation of the nerve impulse, which passes down the nerve fibers of the auditory nerve as neural firings. Thus the Organ of Corti is responsible for transducing sound signals into biological nerve impulses, so that hearing can occur.

(Upper image source: Furness, D., Hair cell of inner ear. Copyright: CC BY-NC 4.0) (Lower image by Janina Luckow)

(Image source: Furness, D., Hair cell of inner ear. Copyright: CC BY-NC 4.0)

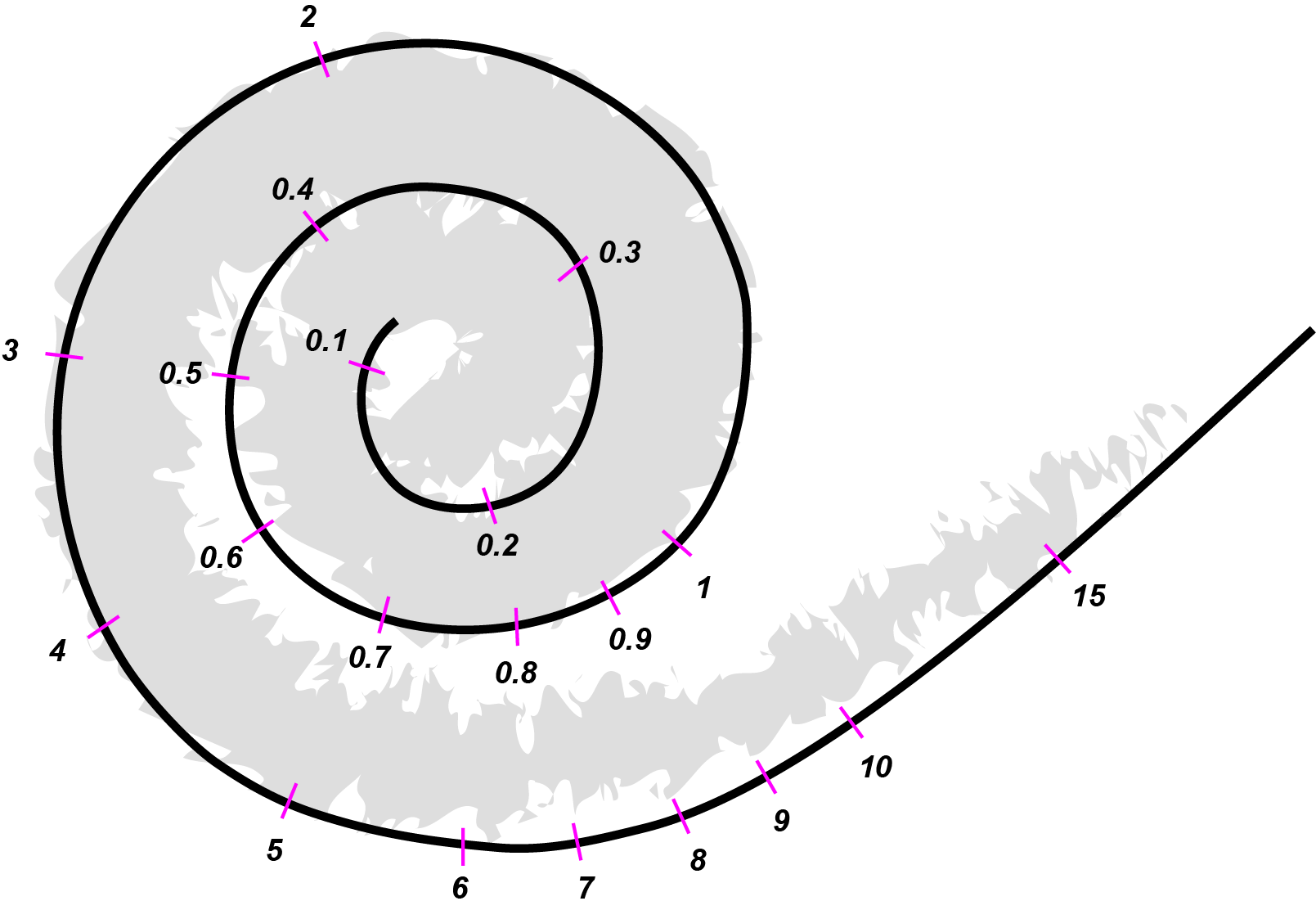

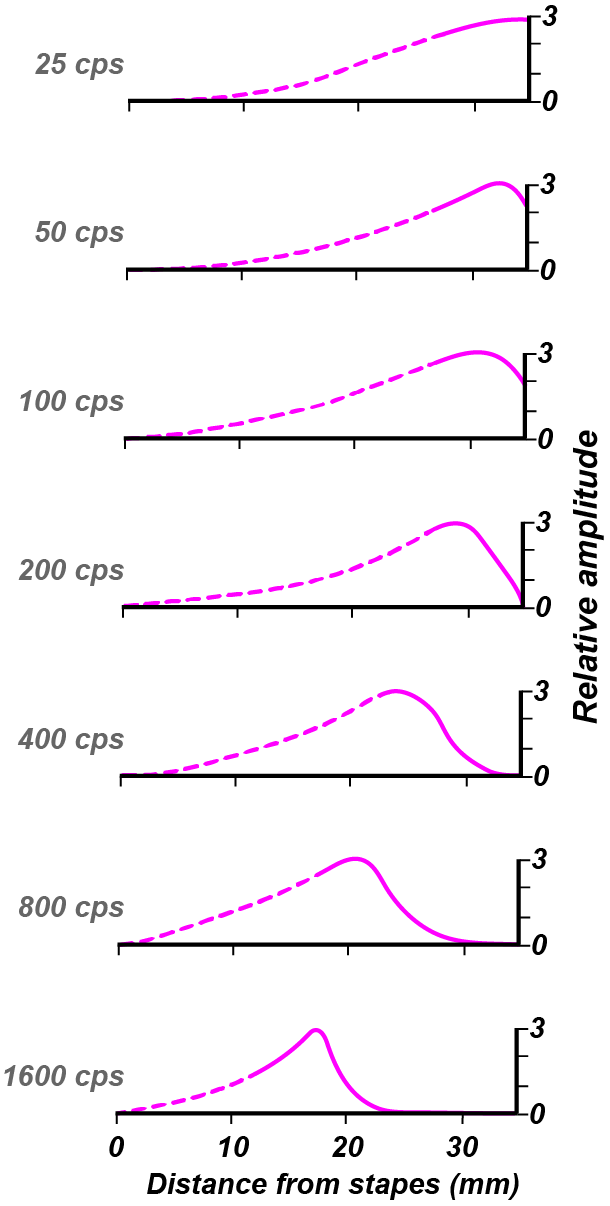

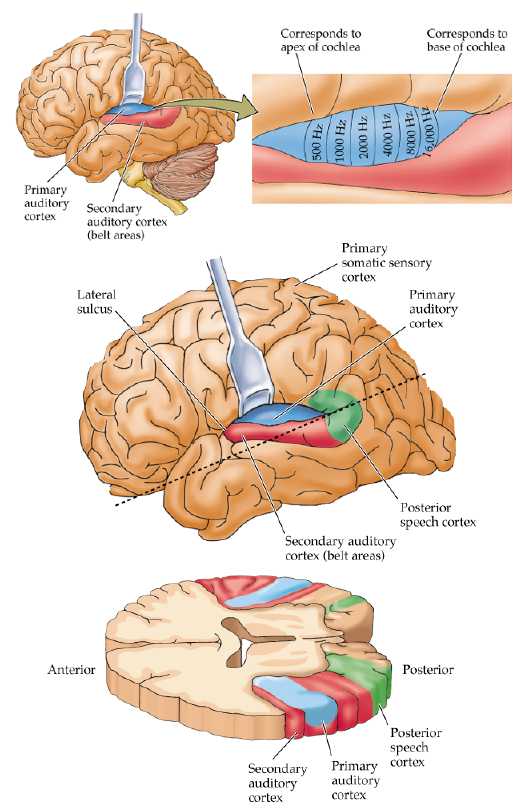

Tonotopic Mapping

The cochlea is a coiled structure, contains the entire length of the basilar membrane. The unrolled cochlea contains the straightened basilar membrane, which is sensitive to a gradient of frequencies. The basilar membrane is tonotopically mapped, which means that different parts of the basilar membrane are optimally sensitive to a gradient of frequencies. The base of the cochlea is sensitive to low frequencies whereas the apical end is most sensitive to the highest frequencies. Tonotopic mapping begins at the basilar membrane and is preserved all the way throughout the auditory system, maintaining its structure until the level of the PrimaryAuditoryCortex.

(Image by Janina Luckow. Adapted from: Port, 2005)

(Animation source: Port, 2005)

(Image by James Cheung. Adapted from: (Watts, 1993))

(Image by James Cheung. Adapted from: Nobel Lectures Physiology or Medicine 1942 - 1962, Elsevier, 1964, pp. 722-746)

The observation of tonotopic mapping on the basilar membrane was first made by Georg von Békésy, who won a Nobel Prize in 1961 for this discovery. This is a diagram from von Békésy’s Nobel lecture, showing that higher frequencies (in cps, or cycles per second) excited the end of the basilar membrane which was closest to the stapes (stirrup). The point of optimal excitation moved further away from the stapes as the stimulus frequency decreased.

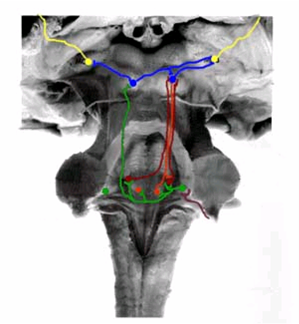

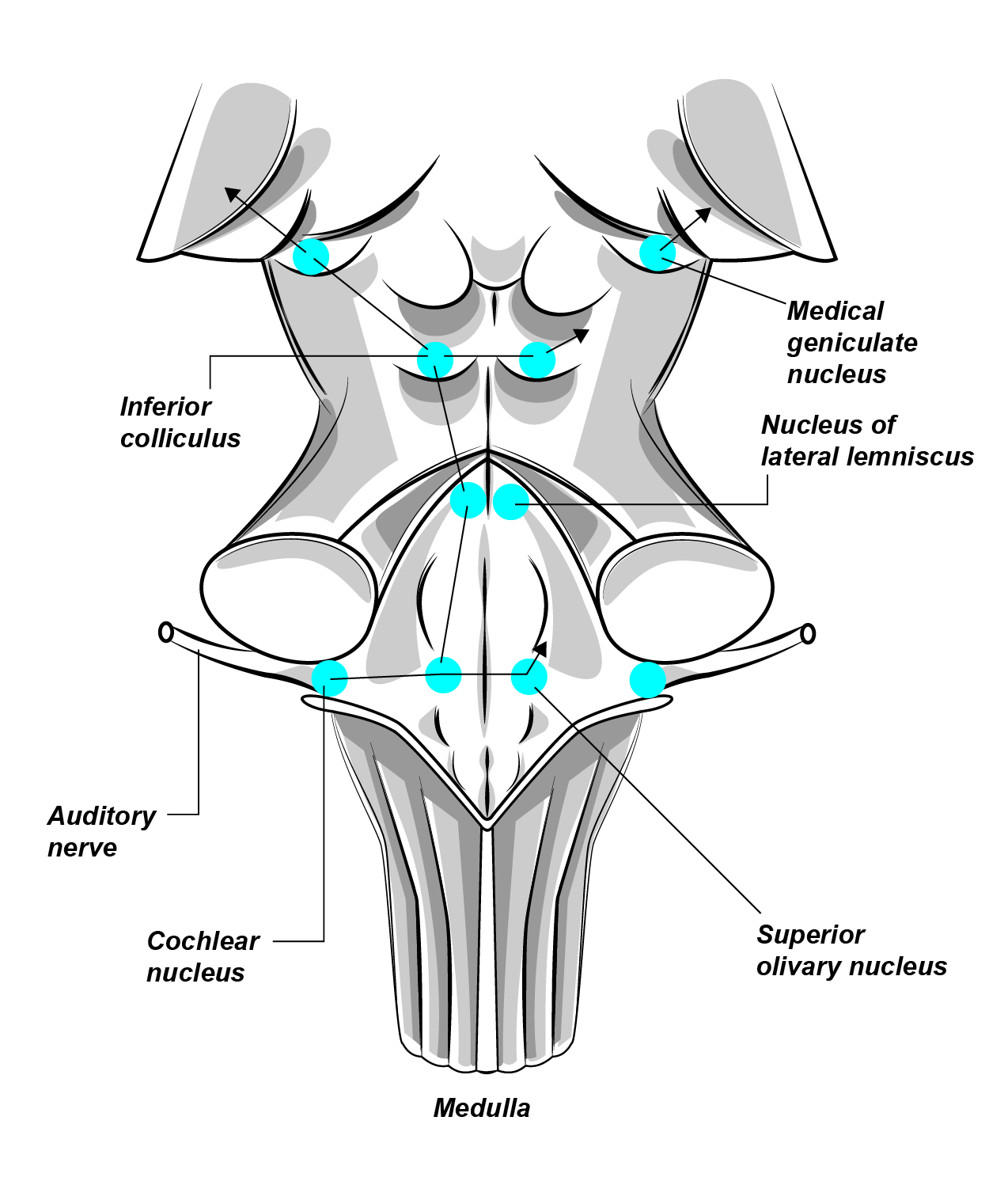

Brainstem Pathways

The brainstem and midbrain include a set of neural regions which relay the nerve impulses passed into the central nervous system via the auditory nerve. Each of these relay centers consists of a group of neurons specialized for computations which are important to the auditory system, such as amplitude change detection and sound source localization.

(Image by Janina Luckow. Adapted from: University at Buffalo)

The auditory nerve leads out of the cochlea and into the brainstem. On the surface of the brainstem, the auditory and the vestibular nerves combine and constitute the VIIIth cranial nerve. A tumor in the VIIIth cranial nerve is called acoustic neuroma and can result in deafness.

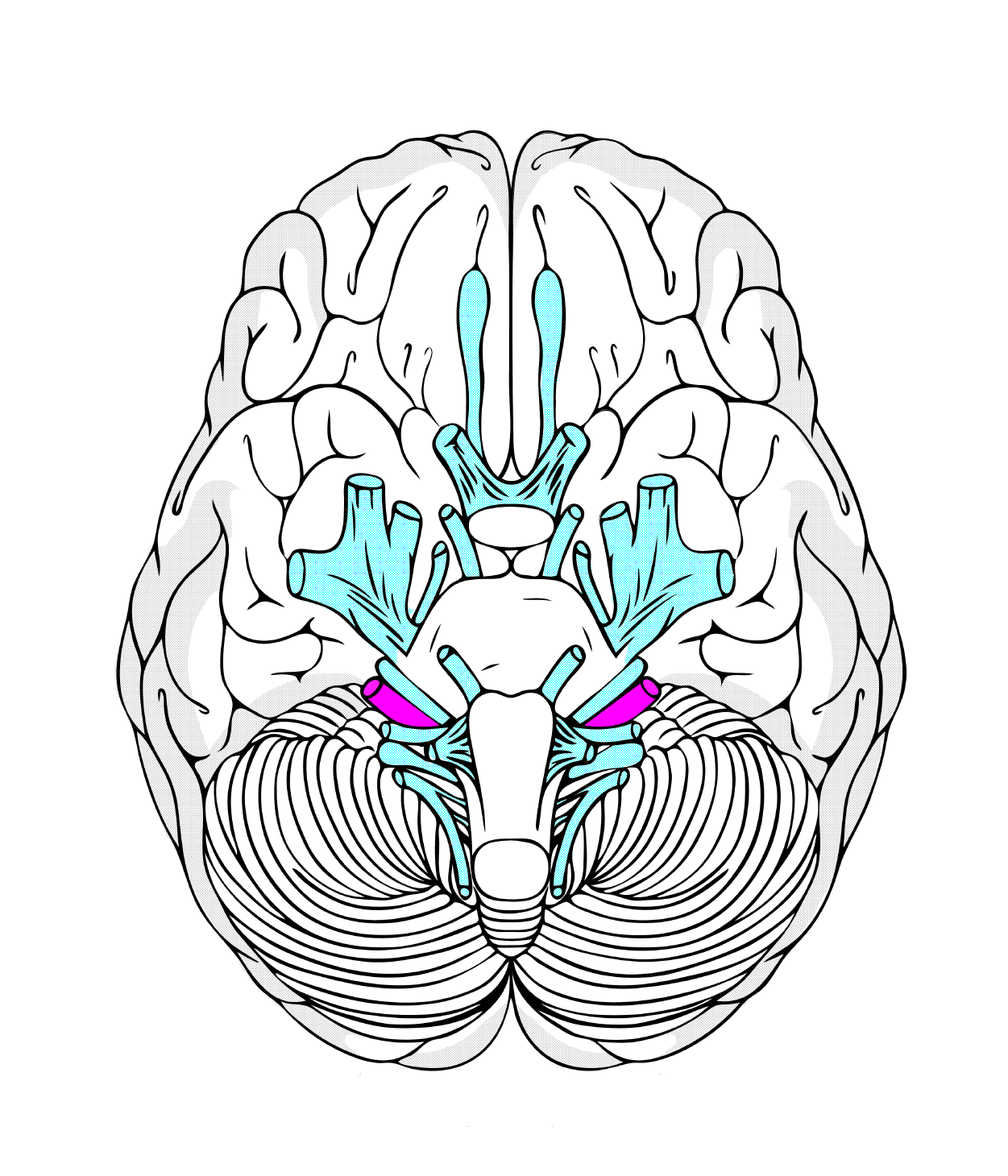

(Image by Janina Luckow. Adapted from: Maricopa Community Colleges)

Overview of the auditory pathway from the brainstem to the cortex.

- Cochlear Nuclei

- Superior Olive, which plays special roles in Binaural Hearing

- Lateral Lemniscus

- Inferior Colliculus, which is especially sensitive to Amplitude Modulation

- Medial Geniculate Nucleus

- Primary Auditory Cortex

The cochlear nuclei (singular: cochlear nucleus) are first relay centers of auditory information in the brainstem, Cochlear nuclei include the dorsal cochlear nucleus and the ventral cochlear nucleus. Both receive input from the auditory nerve, but the dorsal cochlear nucleus is higher up in the brainstem. The cochlear nucleus is the first point along the auditory pathway that generates electrical signals measurable from the scalp. The earliest group of electrophysiological responses that can be recorded from the scalp is called the Brainstem Evoked Response (BER), also known as the Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR). These brain waves consist of a complex of seven components, the first of which is believed to originate from the cochlear nucleus.

The Brainstem Evoked Response. It is a complex of seven waveform components, the first of which are thought to reflect the firing of the cochlear nuclei.

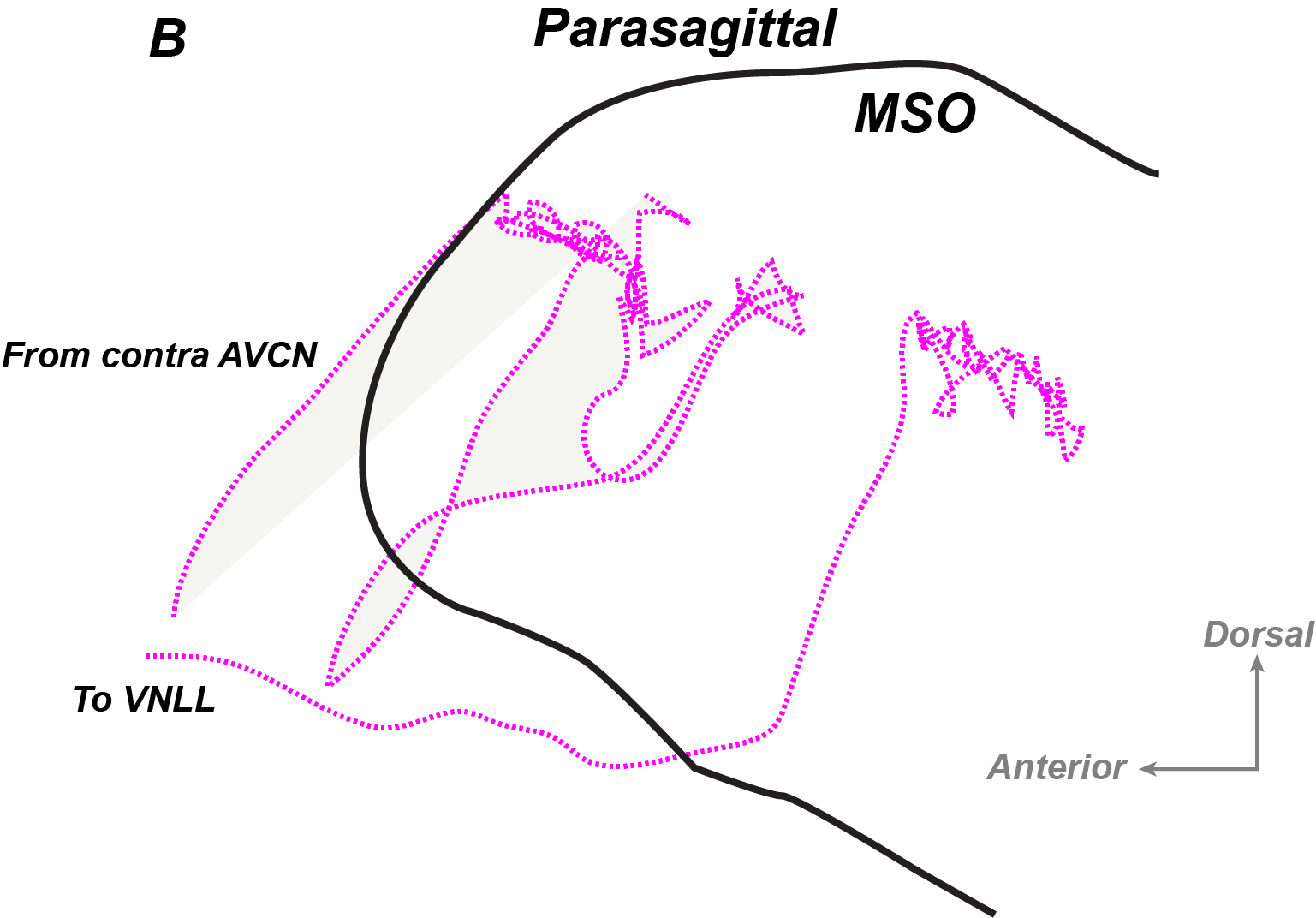

Superior Olive

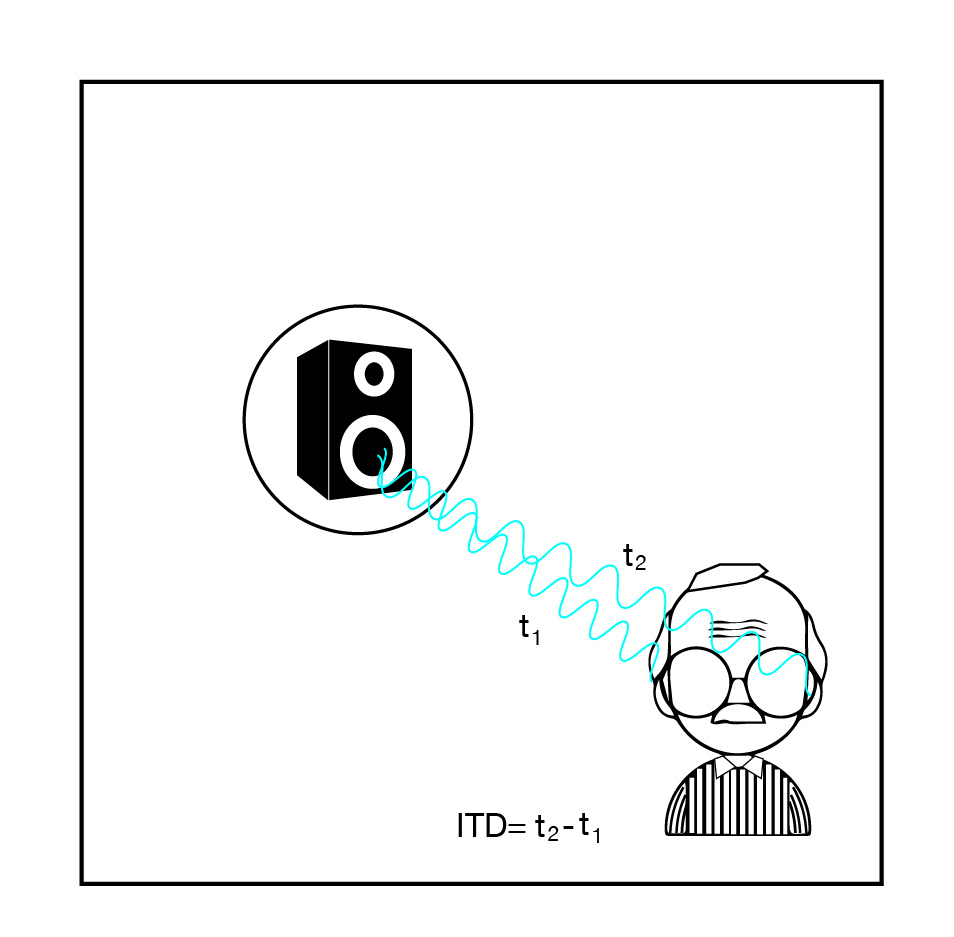

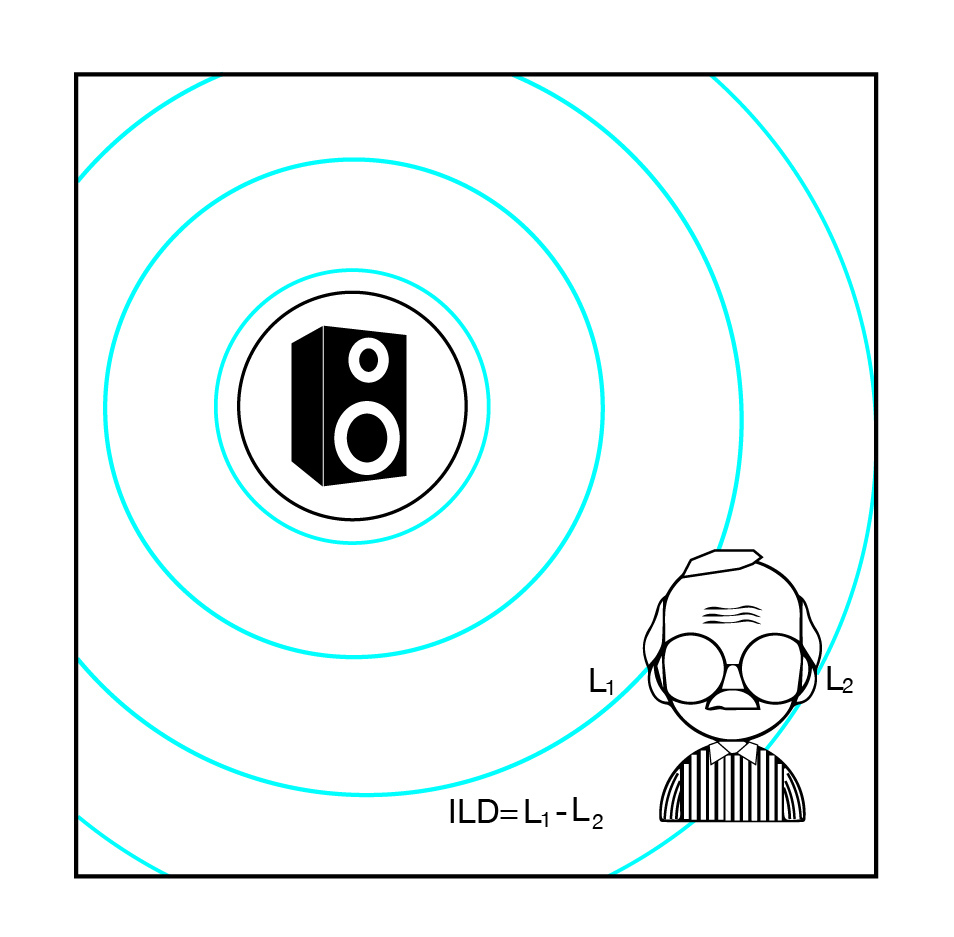

The superior olivary complex include the medial and lateral superior olivary nuclei. These are hubs of neurons that receive input from the dorsal and ventral cochlear nuclei and fire outputs to the nuclei of lateral lemniscus. The superior olivary nuclei are the first along the pathway to receive inputs from both ears, making this complex important for Binaural Hearing. The medial superior olive (MSO) contains more neural representation of low frequencies whereas the lateral superior olive (LSO) has more connections for high frequencies. The MSO compares low-frequency wavelengths to compute the time difference of arrival between the two ears (Interaural Time Differences, ITDs) whereas the LSO compares high-frequency wavelengths to compute the difference in sound level between the ears (Interaural Level

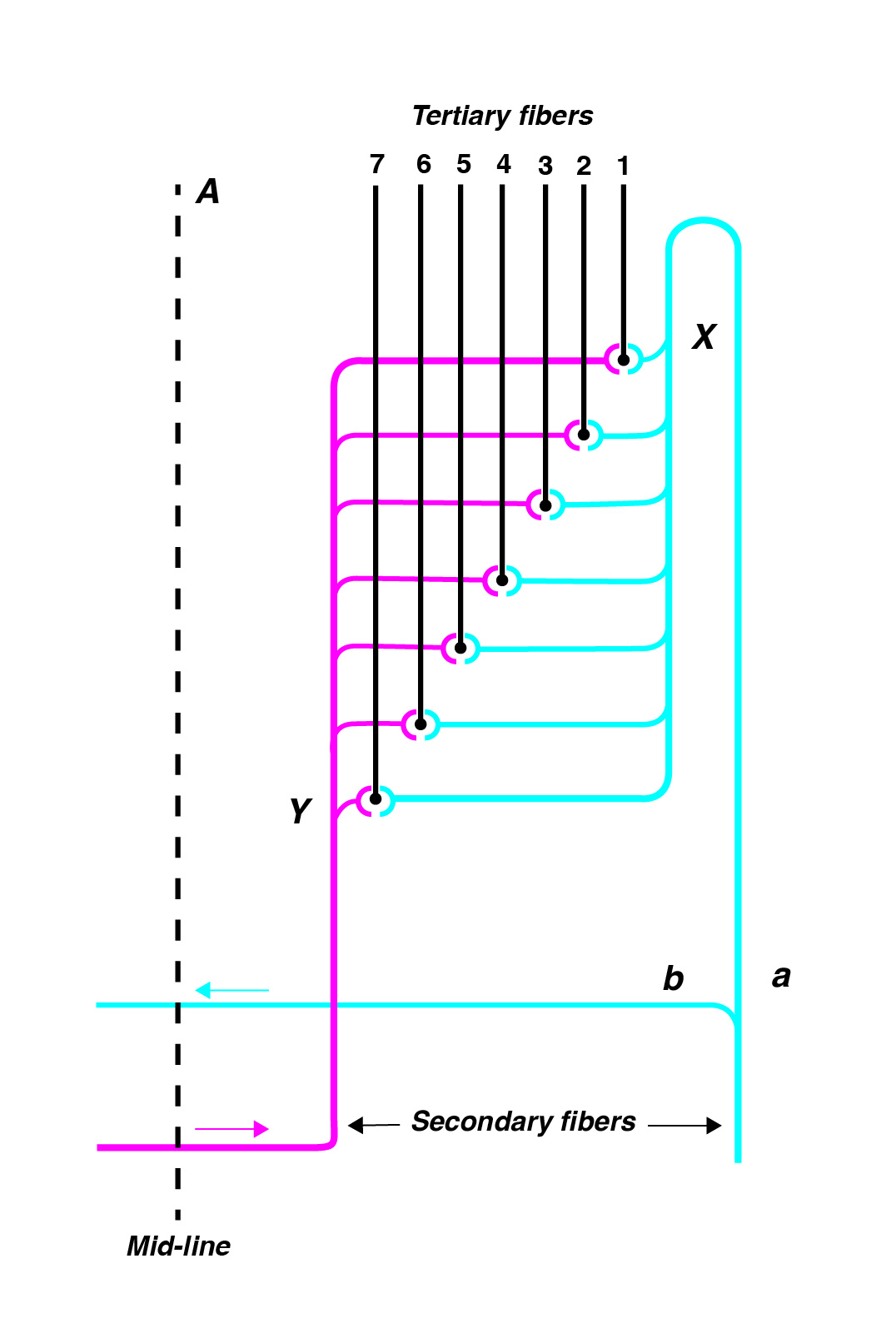

Coincidence detectors in the MSO

The auditory system’s ability to localize sounds depends to a certain extent on the shape of the pinna and the head (see Outer Ear), but the bulk of this amazing ability depends on the binaural system. When sounds arrive from a certain location, the wavefronts arrive at the closer ear first, and the time difference between the arrival times of sound to the closer ear and the further ear is known as interaural time difference, or ITD. Sounds from a certain location also contain more energy at the closer ear compared to the further ear, and this difference in sound levels is termed interaural level difference, or ILD. Since low-frequency sounds have longer wavelengths and are thus more likely to get around the head, ILDs tend to be a more helpful cue for higher frequencies whereas ITDs are more helpful for low frequencies.

Jeffress (1948) proposed a model of how the auditory system computes interaural time differences so as to localize sounds. The model involved a coincidence detector in the brain, in the form of a set of neurons that fire when the two sounds from the left and right ears reach the neuron simultaneously. These coincidence detection neurons were later found in the Nucleus Leminaris of the owl (Carr et al., 1988), which corresponds to the Medial Superior Olive of mammals (Smith et al, 1998). The Lateral Superior Olive was found to be sensitive to level differences between the ears. Since the MSO is sensitive to ITDs and the LSO is sensitive to ILDs, together the superior olivary complex is responsible for much of binaural hearing.

(Image by Janina Luckow)

(Image by Janina Luckow)

(Image by Janina Luckow. Adapted from: Jeffress, 1948)

(Image by James Cheung. Adapted from: (Joris et al., 1998))

Lateral Lemniscus

The lateral lemniscus is anatomically divided into the Ventral, Dorsal, and Intermediate Nuclei of Lateral Lemniscus (VNLL, DNLL, and INLL). Together, these regions receive input from the superior olive to the inferior colliculus. The exact functional role of the VNLL and DNLL are unknown, but these regions are thought to preserve binaural information and are sensitive to amplitude modulation.

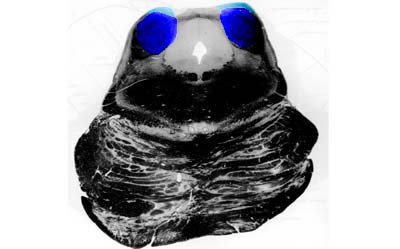

Inferior Colliculus

The inferior colliculus is a collection of nuclei which receives input from the axons of the lateral lemniscus and is located in the midbrain. It operates as a site of early communication between the visual and auditory senses, as well as a feedback-providing mechanism which provides output to the cochlea.

(Image source: University at Buffalo)

The inferior colliculus is one of the most important relay centers in the auditory system. Roles of the inferior colliculus include crossmodal communication, orienting to novel stimuli, providing efferent feedback, and detecting amplitude and frequency modulation.

Crossmodal communication mostly refers to the integration of the visual and auditory sensations. The inferior colliculus is thought to contain a spatial map of auditory space, and may also integrate information with relay centers in visual processing. When confronted with a sudden loud sound, the biological instinct is to turn torwards the source of the sound. This instinct is known as the orienting reflex, and it requires the central nervous system to quickly judge the origin of a sound source, and then engage the visual system to orient towards the location inferred by the auditory system. The inferior colliculus is thought to be necessary for this orienting function.

Efferent fibers are neuronal tracts leading from the brain out towards the periphery. In the auditory system, efferent fibers are found from the inferior colliculus towards to cochlea. This allows the central nervous system, having received information from the periphery, to provide feedback towards the ear. Applications of the central-to-peripheral auditory feedback system include the maintenance of the gain levels of the cochlea, which is adjusted by the outer hair cells.

Modulation detection refers to the ability of the auditory system to detect rapid changes in the signal. These changes in the signal may include amplitude and frequency modulation. These auditory functions are important to speech and music perception, and have been localized to the inferior colliculus.

Amplitude Modulation

One of the roles of the inferior colliculus, and also the inferior colliculus, seems to be to reflect amplitude modulation (McKinney et al., 2001) . Amplitude modulation refers to the change in amplitude levels, usually at periodic rates. In musical performance, playing tremolo typically results in amplitude modulation. AM radio also relies on the application of amplitude modulation.

(Image by James Cheung)

Amplitude modulation can also result in the interaction of two or more tones that are close together in frequency. The interaction of two tones within a critical bandwidth will be discussed in detail in the next unit.

The frequency of amplitude modulation can be represented by the modulation spectrum. The Atlas toolbox, which enables the analysis of the modulation spectrum by plotting the rate of amplitude modulation and its relation to acoustic frequency, is a useful tool to help visualize the rate of change of sounds in both frequency and amplitude. The modulation spectrum plays an important role in speech understanding. Much of the useful information in speech is contained in the modulation spectrum. This is shown by the observation that speech recognition is impaired in an individual with lesions in the inferior colliculus (Hoistad et al., 2003) .

Medial Geniculate Nucleus

The medial geniculate nucleus (MGN) is located In the thalamus, and is the last relay center before reaching the auditory cortex. The thalamus collects sensory input from multiple modalities and relays them to the cortex.

The medial geniculate nucleus contains a division that is tonotopically organized. The primary function of the medial geniculate nucleus is to relay auditory impulses to the cortex.

(Image source: http://sylvius.com)

Also in the thalamus is the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus, responsible for visual capture and orienting.

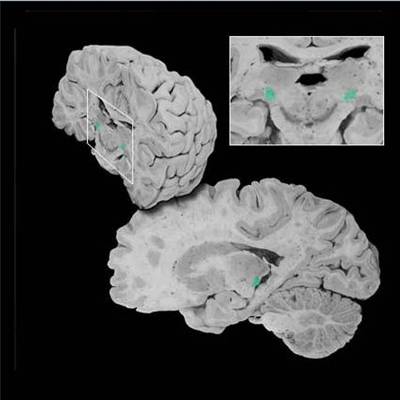

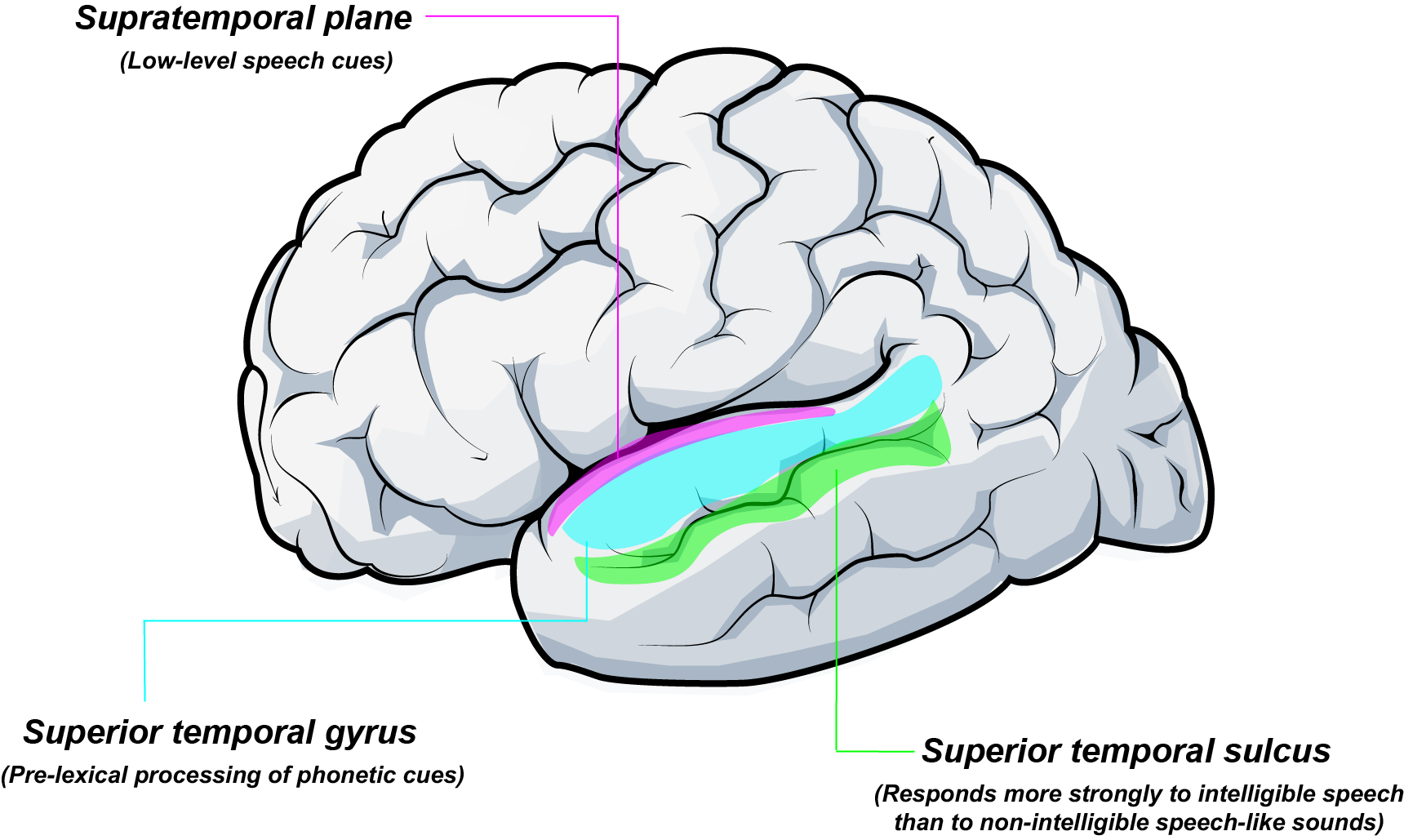

Auditory Cortex

The auditory cortex is located just under the sylvian fissure, which is the fold that divides the temporal lobe from the frontal and parital lobes in the brain.

(Image by James Cheung. Adapted from: Wikimedia Commons)

The auditory cortex includes primary and secondary auditory cortices. The primary auditory cortex (also known as A1) is located on the temporal plane, which is delineated by the Sylvian fissure on the top surface of the temporal lobe. The secondary auditory cortex (A2) surrounds the primary auditory cortex. The primary auditory cortex is tonotopically organized, with the lateral edge of the Sylvian fissure being sensitive to lower frequencies and the medial part of the cortex being sensitive to high frequencies. The primary auditory cortex is responsible for the perception of pitch, rhythm and duration, whereas the secondary auditory cortex is responsible for pattern perception, which includes the perception of speech and melodies. Persons with lesioned auditory cortices have trouble perceiving music; this is a condition known as amusia. (Peretz, 2003)

(Image source: The University of Texas at Dallas)

Primary and secondary auditory cortices. A1 is shown here in blue and A2 is in red. The primary auditory cortex is tonotopically organized.

Primary Auditory Cortex

The primary auditory cortex (A1) is located in the temporal lobe of the cerebral cortex, and is below the Sylvian fissure. A1 is responsive to pitch and duration. Evidence suggest that the left A1 is more sensitive to temporal modulation, thus giving rise to speech perception, whereas the right A1 is more sensitive to spectral modulation, thus giving rise to pitch and music perception. (Zatorre et al., 2001).

Stroke may occasionally (but infrequently) lead to lesions in the primary auditory cortex. People with bilateral A1 lesions can still detect sound, but cannot discriminate between different sounds with the normal level of accuracy. Speech perception, which relies on fine discriminations of sound signals, is severely disrupted in persons with A1 lesions.

Secondary Auditory Cortex

The secondary auditory cortex (A2) surrounds the primary auditory cortex (A1) anatomically. Functionally, A2 is responsible for melody perception, auditory pattern perception, change detection, and perhaps timbre.

The Active Ear

In the auditory world, the auditory system actively engages in various systematic actions to make hearing a constantly changing, active process. In the preceding section on the structure and function of the auditory system, we have outlined the auditory pathway from the ear to the brain, with some mention of the efferent pathways which provide feedback from the central nervous system to the auditory periphery. These feedback pathways are especially seen in the outer hair cells, which receive efferent connections from the midbrain (Inferior Colliculus) down to the auditory periphery, allowing the auditory system to continually adjust its gain levels according to the sound environment. Another role of the inferior colliculus is to orient automatically to any sudden, unexpected sounds in the environment, a rapid mechanism known as the orienting reflex. When an unexpected stimulus startles the sensory system, it immediately captures our attention and drives us to act upon it. This stimulus-driven capture of unexpected sounds has clear evolutionary advantages, and suggests that sensation requires continuous feedback, updating, and reacting.

Taken together, evidence in neuroscience and cognitive psychology suggest that perception, especially auditory perception, is not a passive process, but is an activity in itself. More neuroscientific evidence for active perception will be discussed at a later unit. For a philosophical discussion on the topic of action as perception, see Alva Noe’s Action in Perception book (2005).

Outer Hair Cells

Three rows of outer hair cells are responsible for gain control. There seem to be efferent feedback from the brain which contract or relax the tectorial membrane so as to adjust the gain of the signal they allow to pass through.

Otoacoustic Emissions

Otoacoustic emissions (OAE) are minute sounds produced by the outer hair cells of the cochlea, commonly in response to a sound stimulus. OAE recording, in combination with the recording of ABRs (see Cochlear Nuclei), is performed frequently on infants as a screening test to assess an infant’s hearing. The recording is performed by placing a small probe that contains a microphone and speaker into the infant’s ear. Sounds are generated in the probe and responses that come back from the cochlea are recorded. Once the cochlea processes the sound, an electrical stimulus is sent to the brainstem. In addition, there is a second and separate sound that does not travel up the nerve, but comes back out into the infant’s ear canal. This “byproduct” is the otoacoustic emission. The emission is then recorded with the microphone probe and analyzed by audiologists. A normally functioning auditory system should emit OAEs in response to sounds at speech-like frequencies. OAE recordings are not only useful as screening tests; they can also be used as a research tool to assess the responsivity of the auditory system. Importantly, OAEs can also be obtained from other animals and are an indication of a healthily functioning ear.

Evolution Of The Auditory System

So far we have comprehensively discussed the anatomy and physiology of the human auditory system. It is important to consider how such a complex system has evolved to enable music perception for humans today. A comparison of the auditory system between humans and other species reveal that various nonhuman mammals do have auditory system analogous to humans. Monkeys, cats, chinchillas, marmosets, rats, and various other mammals all make use of pathways in their peripheral and central nervous system, from the ear to the brain, to analyze and react to sounds, although the precise points along these pathways may differ slightly among species. Birds, fish, and amphibians are also known to have auditory pathways and to analyze sounds in a reasonably similar manner. Taken together, auditory systems in all these animals probably share the same evolutionary origins as the human auditory system.

Fay and Popper (Fay et al., 2000) argued that all vertebrate auditory systems are required to do certain basic tasks including acoustic feature discrimination, sound source localization, frequency analysis, and auditory scene analysis, among others. These sorts of capabilities arose very early in the evolution of the vertebrates and have been modified by selection in different species. While various animals are able to hear and have auditory systems, only a few species have evolved to make music.

Music in Other Species

While the act of music making is universal to all cultures in human society, only a few species of animals are known to make music systematically. Nonhuman species that sing include birds, whales, and monkeys.

(Audio source: Wikimedia Commons)

(Max Patch by Víctor Gutiérrez and John MacCallum)

You can have access to all MUTOR interactive Max patches when you clone the MUTOR github repository and place it inside the Max search path.

The ferret and chinchilla auditory systems are similar to ours in that most of the auditory apparati are similar anatomically and functionally to the human auditory system. This makes them a good animal model to study. Bats are also of interest because of their ability to hear very high frequencies. Bats emit ultrasonic frequencies (sounds beyond our hearing range in frequency) and listen for the reflected sounds in order to determine their own location. The use of echoes to find out one’s own position in space is known as echolocation.

Hearing Damage

Hearing damage is very prevalent, especially among rock musicians and individuals who are continually exposed to loud sounds.

Famous people suffering from hearing loss (Adapted from H.E.A.R.):

- Barbra Streisand

- Bedrich Smetana

- Bill Clinton

- Bono

- Burt Reynolds

- Charles Darwin

- Cher

- David Letterman

- Cheryl Tiegs

- Don Imus

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Pete Townshend from The Who speaks about hearing loss

- Clive Barker

- Dwight D. Eisenhower

- Eric Clapton

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Jeff Beck

- Keanu Reeves

- Kevin Shields

- Larry King

- Lars Ulrich

- Leonard Nimoy

- Liberty Divito

- Lorence Henderson

- Martin Luther

- Michael Church

- Ludwig Van Beethoven

- Michael Tomlinson

- Mick Ronson

- Morgan Fairchild

- Motorhead

- Neil Young

- Paul Schaffer

- Neve Campbell

- Pete Townshend

- Ozzy Ozborne

- Peter Jennings

- Phil Collins

- Richard Thomas

- Rick Emmett

- Robert Schumann

- Roger Miller

- Rosalynn Carter

- Steve Martin

- Stewart Copeland

- Sting

- Sylvester Stallone

- Ted Nugent

- Thomas Edison

- Tony Franklin

- The Edge

- Tony Randall

- Trent Reznor

- Vanilla Fudge

- William Shatner

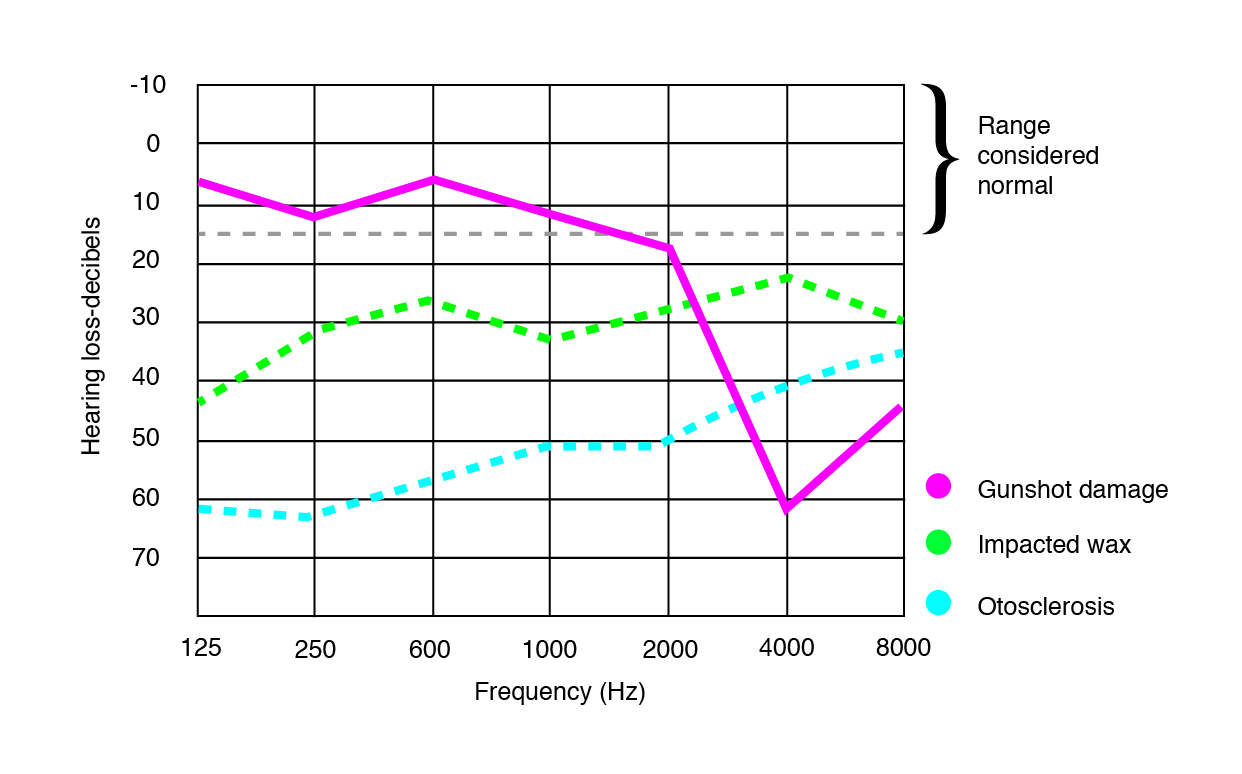

How do you know when you have damaged hearing?

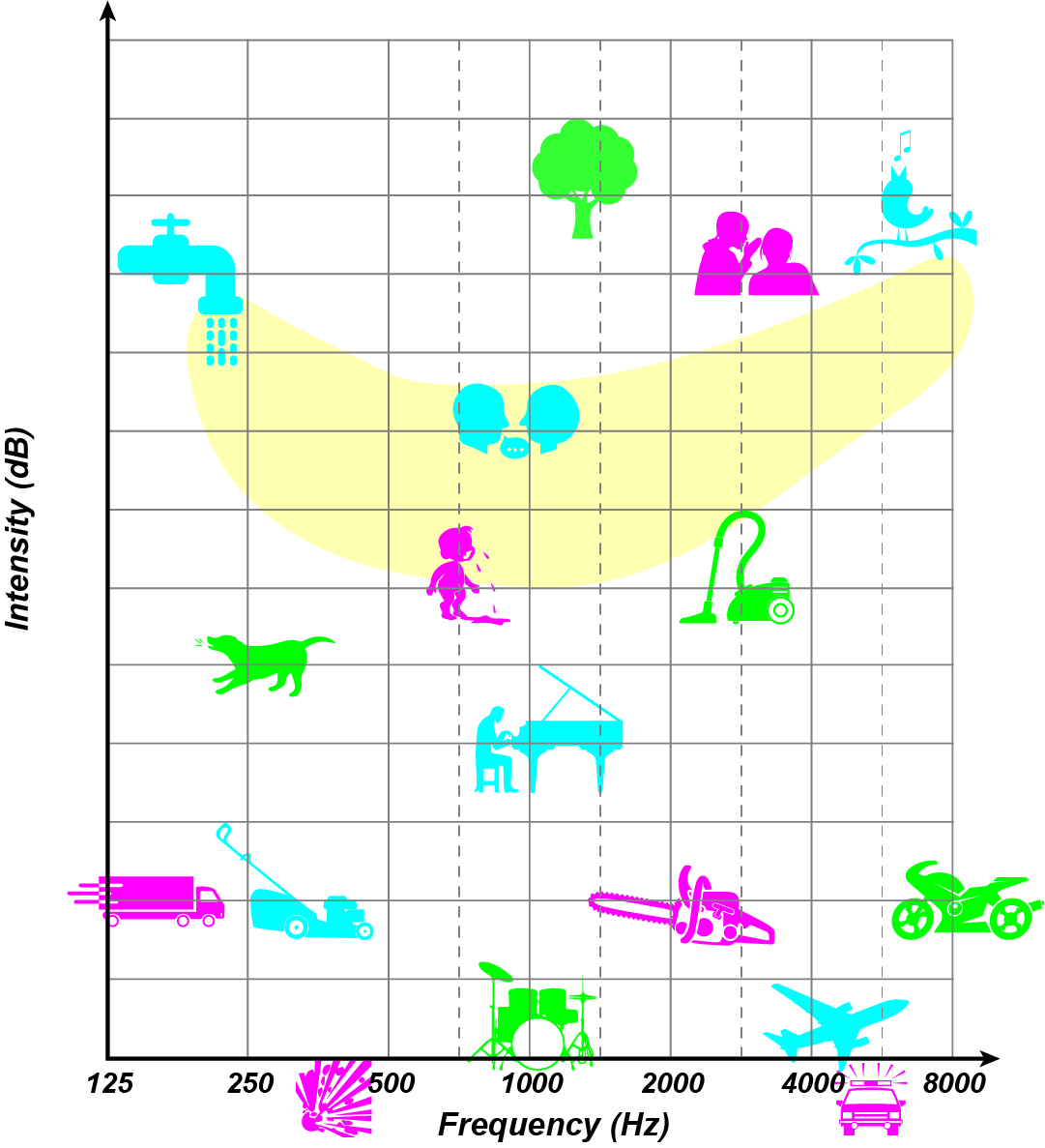

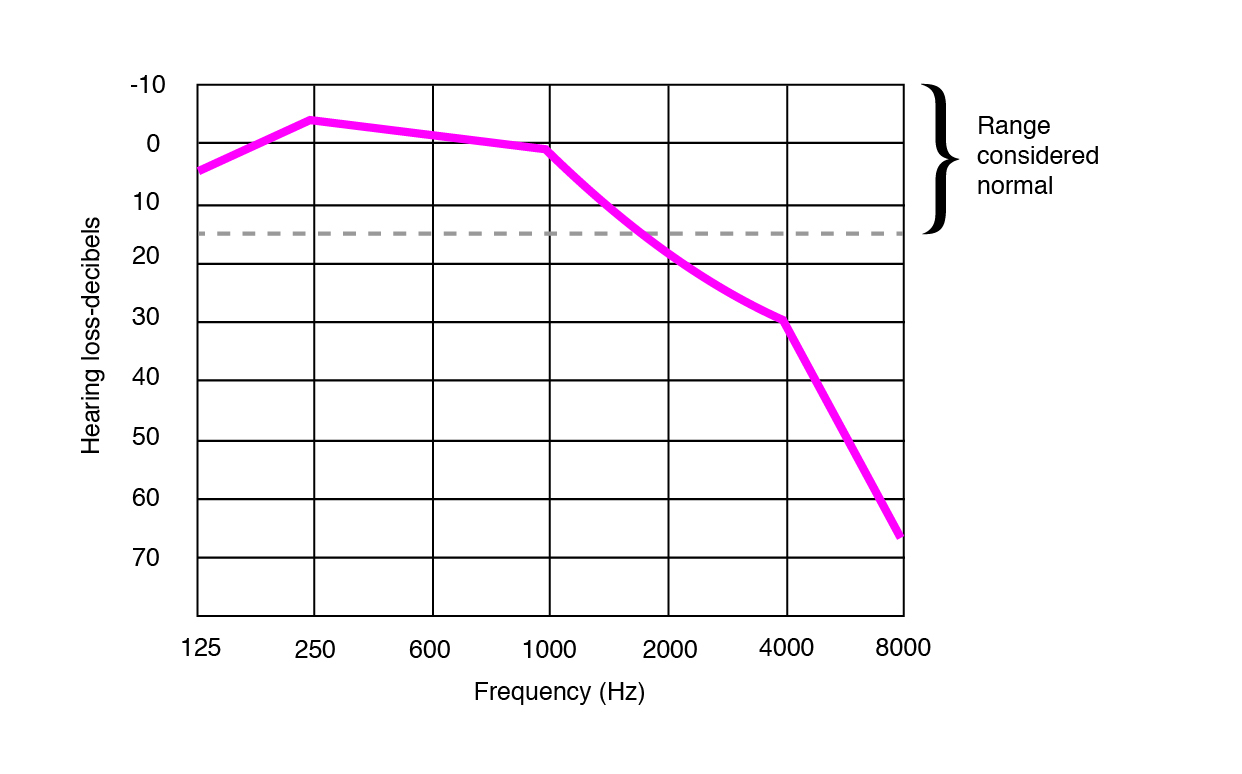

Audiologists can administer a pure-tone audiogram to find your threshold and range of hearing. The test involves finding the threshold of hearing for pure tones of different frequencies. The resulting chart is an audiogram, which relates the hearing level (in decibels) to frequency. A 0dB hearing threshold is equivalent to optimal performance. A louder threshold (higher in dB) signifies increased hearing loss. The severity of hearing loss is summarized in the chart below.

Ranges of hearing loss:

- -10dB to 25dB = Normal range

- 26dB to 40 dB = Mild hearing loss

- 41 dB to 55 dB = Moderate hearing loss

- 56 dB to 70 dB = Moderately Severe hearing loss

- 71 dB to 90 dB = Severe hearing loss

- over 90 dB = Profound hearing loss (source: Audika)

Examples of Audiograms

|

| |

(Audio source: Truax, B., Handbook for Acoustic Ecology. Licensed by copyright owner)

The first part of this sentence is played normally, whereas the second part is filtered so as to simulate the percept of an individual with high-frequency hearing loss.

(Image source: Truax, B., Handbook for Acoustic Ecology. Licensed by copyright owner)

(Image by James Cheung)

(Image by James Cheung. Adapted from: Ling, D. & Ling, A (1978). Aural Habilitation)

Types of Hearing Loss

Types of hearing loss are categorized by the site of biological abnormality. They commonly include conductive hearing loss, sensorineural hearing loss, and mixed hearing loss. In addition to these three types of hearing loss, cortical deafness and tinnitis are also causes of impaired hearing.

Conductive hearing loss

Conductive hearing loss is hearing damage due to obstruction, injury, or disease in the outer or middle ear. This may be due to ear infections, the buildup of earwax in the ear canal, fluid buildup in the Eustachean tube (which may be due to the common cold), or a biological malformation of the middle ear ossicles. Conductive hearing loss can be cured if the abnormality is reversible; for instance, curing an ear infection with antibiotics will restore hearing.

Sensorineural hearing loss

Sensorineural hearing loss refers to damage in the cochlea or the auditory nerve. Most commonly this involves damage in the inner and/or outer hair cells on the basilar membrane of the cochlea. Sensorineural hearing loss may result from old age, exposure to loud noises, and some drugs such as streptomyosin and other antibiotics which, when taken in large dosages, result in damage to the hair cells and the auditory nerve.

Presbyacusis is the loss of hearing as a result of old age. The hearing loss quite common and is most prominent at high frequencies. While the healthy young individual can hear an optimal frequency range of 20-20,000Hz, The average 50 year old can no longer hear above 17,000Hz. Because of the shape of the audiogram, which relates audibility to frequency, the loss of high-frequency hearing due to sound exposure and old age is termed ski-slope hearing loss.

Presbyacusis is commonly observed as a “ski-slope” hearing loss, where “ski-slope” refers to the shape of the audiometry function, which is relatively intact at low frequencies, but falls off rapidly at high frequencies. (Image by Janina Luckow. Adapted from: Hearing Life)

Mixed hearing loss

Instead of only conductive or sensorineural hearing loss, individuals occasionally have damage in both the conductive and sensorineural parts of the auditory system.

Cortical deafness

A third, and relatively rare, type of hearing loss results from lesions to the auditory cortex. Although these individuals are able to detect sounds, they often show impairment in pitch and speech perception. Cortical deafness is irreversible.

Tinnitus

When in quiet environments, we may occasionally hear a ringing in the ears. This is a result of shape changes in the outer hair cells, and is especially prominent immediately after exposure to loud sounds (e.g. immediately after leaving a rock concert). While this occurs to a small extent for most individuals, it occurs to a bothersome degree to some individuals with hearing damage. Abnormally frequent tinnitus is also a kind of hearing damage.

Ways To Protect Hearing

- Avoid loud sounds.

- Use protection for your ears.

(Image source: Pixabay. Copyright: Pixabay License)

(Image source: Wikimedia Commons. Copyright: CC BY-SA 3.0)

A rock concert generally produces sounds at around 100dB. While this is an extremely loud baseline of sound level, rock concerts tend to have relatively little dynamic variation. Sounds of 120dB or more are perceived as painfully loud.

Hearing loss has been observed in individuals who are exposed to sounds at or above 100dB for two or more hours, and in individuals exposed to sounds 85dB or louder for eight or more hours. Relatively infrequent noise exposure can result in a temporary threshold shift, but repeated episodes of noise exposure will lead to permanent hearing damage.

Protecting Your Ears

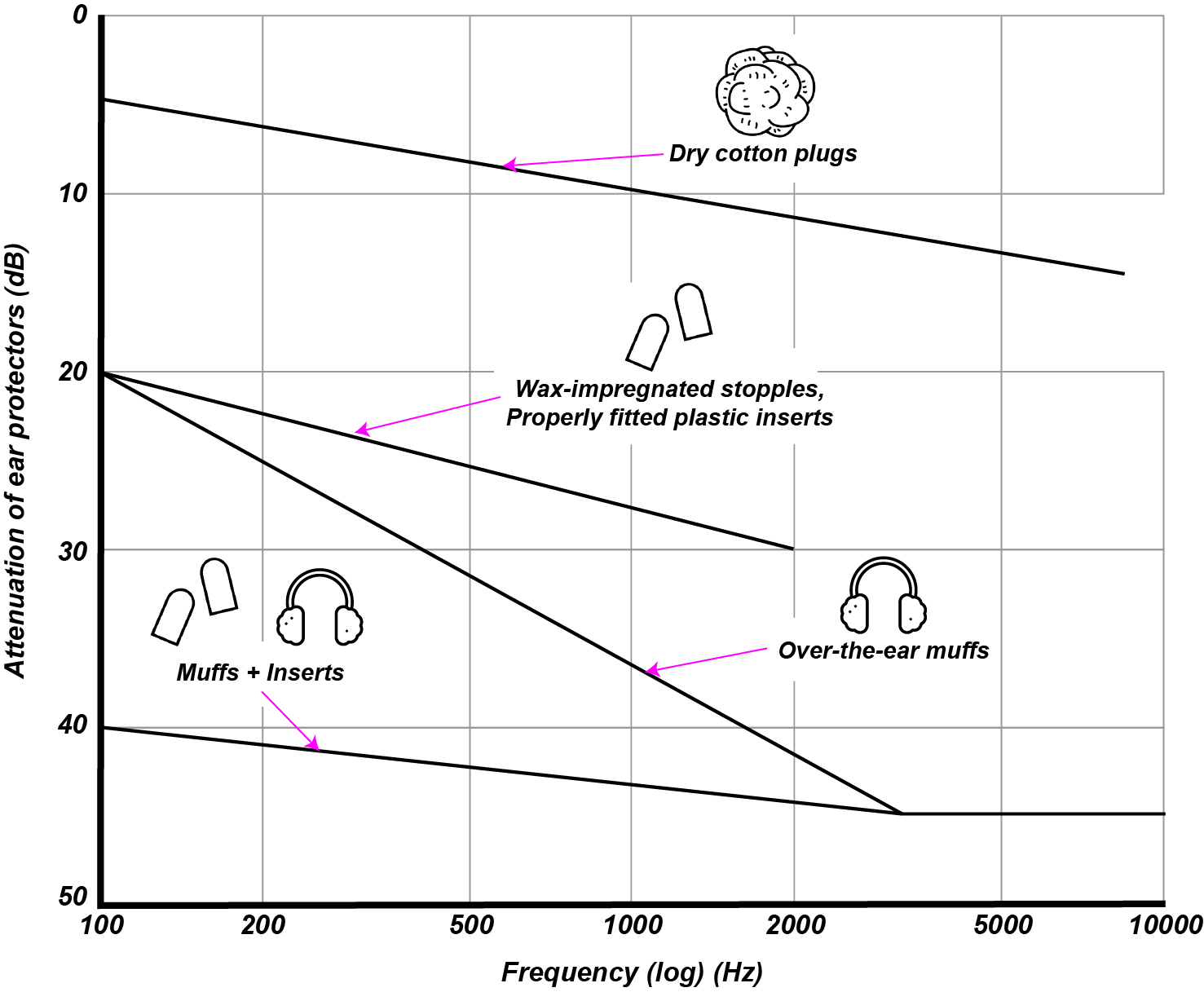

If you are continually exposed to sounds above 85dB, you should wear protective gear to avoid hearing damage. Various protective gear are available and useful in attenuating sound vibrations to the ear. Disposable ear plugs, most commonly made of cotton, or foam, can be inserted into the ear canal. They are effective in reducing noise by around 10dB. One can also get musicians’ earplugs, or plastic earplugs fitted with rubber inserts that filter out sound. These can be custom made according to a mold of the user’s ears. Custom-made earplugs provide 15-30dB of noise reduction, which makes them superior to foam or cotton earplugs, and can be used in loud environments such as rock concerts.

For more powerful hearing protection, especially from sudden sounds such as gunshots, one can purchase over-the-ear muffs, which provide up to 40dB of sound attenuation. To ensure maximal hearing protection, the best strategy is to combine the uses of earplugs and ear muffs, as their added contribution to sound attenuation is more effective than their individual contributions.

(Image by James Cheung. Adapted from: Rossing, Moore & Wheeler, 2001) Various types of hearing protection and their noise reduction rates, as a function of frequency.

Summary

In this unit we have comprehensively covered the structure and function of the auditory system, from the auditory periphery, which includes the out, middle, and inner divisions of the ear, to the central nervous system, which includes the brainstem and midbrain auditory pathways as well as the auditory cortex. We focused on the structure and function of the cochlea as a tonotopic frequency analyzer, and the superior olive as a site for binaural hearing, the inferior colliculus as the site for feedback and amplitude modulation. The ear should be conceived as an actively perceiving process, instead of a passive organ.

We also compared our musical system with animals of other species. Finally, we looked at when the auditory system malfunctions - what the various types of hearing loss are, how they are detected, and how to protect your own hearing.

Quiz

Lay out the anatomy of the auditory pathway, from the cochlea to the primary auditory cortex.

How does the structure of the basilar membrane reinforce its function?

Which of the following is most heavily implicated in being able to perceive location of sound sources?

- inferior colliculus

- cochlea

- medial geniculat enucleus

- superior olivary nuclei

Which of the following methods of hearing protection is the most efficient at attenuating sound?

- earmuffs

- cotton earplugs

- plastic inserts

References

- Griffiths, T. “The neural processing of complex sounds”. In Cognitive Neuroscience of Music, Peretz, I. & Zatorre, R (Eds.), pp. 168-180. Oxford University Press. 2003.

- Peretz, I. “Brain specialization for music: new evidence from congenital amusia”. In Cognitive Neuroscience of Music, Peretz, I. & Zatorre, R (Eds.), pp. 192-203. Oxford University Press. 2003.

- McKinney, M.F. & Tramo, M.J. & Delgutte, B. “Neural correlates of the dissonance of musical intervals in the inferior colliculus”. In Physiological and Psycophysical Bases of Auditory Function. D.J. Breebaart, A.J.M. Houtsma, A. Kohlrausch, V.F. Prijs, and R. Schoonhoven (Eds), pp. 83-89. Maastricht: Shaker. 2001.

- Fay, R.R. & Popper, A.N. “Evolution of hearing in vertebrates: the inner ears and processing.”. Hearing research, 149: 1-10. 2000.

- Hoistad, D.L. & Hain, T.C. “Central hearing loss with a bilateral inferior colliculus lesion”. Audiol and Neurootol 8(2): 111-113. 2003. 10.1159/000068999

- Hauser, M.D. & McDermott, J. “The evolution of the music faculty: a comparative perspective.”. Nature Neuroscience, 6: 668-668. 2003.

- Watts, L. “Cochlear Mechanics: Analysis and Analog VLSI”. Doctoral dissertation. 1993.

- Carr, C.E. & Konishi, M. “Axonal delay lines for time measurement in the owl’s brainstem”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 85: 8311-8315. 1988.

- Joris, P.X. & Smith, P.H. & Yin, T.C.T. “Coincidence Detection in the Auditory System”. Neuron, 21(6): 1235-1238. 1998. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80643-1

- Zatorre, R.J. & Belin, P. “Spectral and temporal processing in human auditory cortex.”. Cerebral Cortex, Vol. 11: 946-953. 2001.

- Liberman, M.C. & Dodds, L.W. & Pierce, S. “Afferent and efferent innervation of the cat cochlea: quantitative analysis with light and electron microscopy”. Journal of Computational Neurology, 301(3): 443-460. 1990. 10.1002/cne.903010309

Authors

Topics

- Auditory Pathway

- Structures and functions

- Active Ear

- Evolution of the Auditory System

- Music in other Species

- Hearing Damage