Unit 11: Situated Instrument Design: Towards an ecological approach to media performance

Synopsis

An overview on the history and theory of instrument design from a multimedia art practitioner perspective. Beginning with pre-historical developments, we will think into the human-object relationship and examine some of the social, political, and mystical implications of the incorporation of bodies and objects in performance practice, and discuss some of the key considerations that go into designing interactive instrument systems in different scales and contexts. In connection with these ideas, I will give a brief introduction to my use of computer vision in scenographic video-puppet-instrument performances.

- Introduction

- Instruments, tools, things

- Embodiment with things

- Embodied learning, affordances and constraints

- Body-instrument persona

- Origins of logistics and data science

- Homogeneous data, Capitalism, Containerization

- Encoding of knowledge

- Instrument system components

- Computer assisted performance/composition

- Importance of context, distributed agency

- Computational agents

- Puppetry and strong AI

- Mapping strategies

- Audio-visual relationships

- Representational instruments

- Glitch and meta-systems — and object realism

- Tactile listening, texture space

- Recent work with video puppet instruments

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

This talk is going to give a brief introduction to my thinking about instrument and interaction design as an artistic practice, focusing on human-object relationships and the social contexts that frame these interactions.

We will wind our way through a forest of various points of interest, traveling towards what I think of as an ecological approach to media performance.

As a framework for thinking through these ideas, I am drawing on my own artistic practice and the research that went into a course called “Situated Instrument Design” that I developed some years ago at UC Berkeley’s Center for New Music and Audio Technologies (or CNMAT).

The class was centered on the instrumental system design research of David Wessel and Adrian Freed at CNMAT, and the ideas that flowed from their innovative work in the theory and practice of human computer interaction and realtime electronic sound, based on David Wessel’s background in cognitive science and free improvisation.

Like Wessel, my own background in music came largely through the practice of improvisation, and in many ways I think of composition, and process of developing instrument systems, as different modes of instrumental practice.

And this experience of instrumental performance, forming close relationships objects, has proven to be a key element in developing a holistic and open-ended framework of what the idea of “instrument” means, or could mean.

Instruments, tools, things

Ok, so… what is an instrument exactly?

Is it a:

mechanism?

utensil?

appliance?

equipment?

device?

contraption?

contrivance?

gadget?

gizmo?

a form of labor-saving technology?

The Oxford Dictionary defines an instrument as:

- instrument

- A tool or implement, especially one for precision work.

- A means of pursing an aim.

- A person who is exploited or made use of.

- A measuring device used to gauge the level, position, speed, etc. of something, especially a motor vehicle or aircraft.

- An object or device for producing musical sounds. (also musical instrument)

- A form or legal document. (Lexico, 2021)

So, I think interesting here is that music is not the first meaning. Of course it depends on the dictionary, don’t forget that dictionaries are also editorial instruments that express the curated ideas of the people who put the dictionary together! I actually made a piece about this once a long time ago.

Also interesting is that none of the definitions really seem complete; they are all somewhat circular, referring to other synonyms that were in our list. We learn that an instrument is a type of tool. Ok. But, let’s see if we can follow the path of definitions until we find something general enough to think about multimedia.

When we look up the word tool we learn that a tool is:

- tool

- A device or implement, especially one held in the hand, used to carry out a particular function. (Lexico, 2021)

And then if we then look up device we see that a device is:

- device

- A thing made or adapted for a particular purpose, especially a piece of mechanical or electronic equipment. (Lexico, 2021)

A device is also listed as being a bomb or other explosive weapon, so we can learn something about our human editors here.

So here we have thing. A thing is a useful idea, and seems to give us a lot of leeway to define as we see fit for a given situation. Since we are talking about instruments in the artistic/multimedia context, we want our definition to have room to consider an instrument in as many ways as possible.

If we go a bit further, we find the definition of thing is:

- thing

- An object that one need not, cannot, or does not wish to give a specific name to.

- An inanimate material object as distinct from a living sentient being.

- An action, event, thought, or utterance. (Lexico, 2021)

I love this first definition! “An object that one need not, cannot, or does not wish to give a specific name to.” So, a thing is an object. Beyond that, the dictionary can’t give it a name. But you may wish to if you feel the need. And here we can see aesthetic choice starting to enter the picture.

Turning to the definition of object, we reach a point of recursion; an object is also a thing.

An object is defined as:

- object

- A material thing that can be seen and touched.

A thing external to the thinking mind or subject.

- A person or thing to which a specified action or feeling is directed.

A goal or purpose (Lexico, 2021)

This dictionary dive is not just an etymological exercise, these meanings can really have a direct and tangible influence in the way we create and use things in making art.

So, the thing-object seems to imply something (anything) that is not us—the subjective sensing person. This definition of thing also mentions the sense of an external otherness, which is a deep part of the way we situate ourselves in our environments. But of course from the other peoples’ prospectives we are ourselves also some kind of otherness, so I think really everything is a thing.

We are constantly seeing, feeling, sensing the world, which is made of things. When these things are “a tool or implement, especially one for precision work”, then we might typically call them, instruments. And we have learned to do all sorts of different things by interacting with objects. We are doing-things with things!

Embodiment with things

Historian and environmental philosopher Melanie Challenger, writes in her recent book, How to Be Animal: A New History of What it Means to Be Human (2021):

“Life on our planet can be arranged, more or less, into autotrophs and heterotrophs, organisms that exploit energy from the sun or chemical reactions, and organisms that take energy from those who’ve already captured it. What is unusual about our species is that we’ve been able to use more and more energy without having to evolve into a different species. We’ve achieved this through a combination of social learning, complex culture, and technologies. We don’t have to speciate to gain the claws of an allosaurus; we can share information to design a warhead or a power station. In other words, we change our tools rather than our bodies.” (Challenger, 2021)(p.15)

So in other words, we have evolved through social learning and culture to develop new tools, devices, objects that allow us new capabilities for action and utility. The tools become extensions of ourselves. As Marshal McLuhan writes:

“During the mechanical ages we had extended our bodies in space. Today, after more than a century of electric technology, we have extended our central nervous system itself in a global embrace, […]” (McLuhan, 1964)

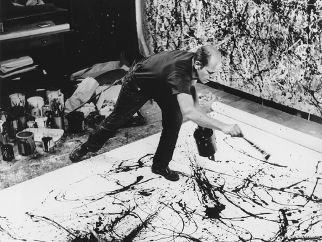

Artists know this very well, as we must think, imagine, feel and create forms, through the mediation of tools. We call performing musicians instrumentalists, who spend much of their lives devoted to the nuanced control of one particular type of instrument. Each art form has its own set of instruments; paintbrushes, knifes, glue, and so I think we can also include every artist as an instrumentalist.

For some artists like dancers and vocalists, the body is the instrument, or for other media like works of relational and participatory art, the conceptual framing of the situation and social context might be created through the instrument of language or architecture.

Each instrument can become a kind of lifestyle—we tend to identify with our instruments in intimate way. They are symbolic of different modes of expression, influencing our perspectives on articulation, and like language, mediate our thinking about of how different kinds of actions might fit into different social situations.

Our bodies also physically change as a result of this close relationship with our tools. String players develop calluses on their finger tips from the pressure of the strings against the flesh. Violinists and Violists will often have a little red mark on their chin, and so on.

I broke my arm once skiing, and had the cast slightly angled so that I could continue playing guitar while it was healing. Luckily there was no lasting damage from this, but in some cases instrument technique itself can cause lasting damage, for example for brass players this can be a problem.

Some instrumentalists will do extreme exercises thought to improve technique—Robert Schumann famously ruined his career as a pianist by using extreme finger stretching technologies of his day.

This intensity of the artist’s relationship to their tools is a byproduct of the intensity of the potential throughput in this incorporation of tools with our physical gestures.

So this is deep incorporation—stemming from the Latin in corpus; into the body. When we reach a level of fluency with a tool, we don’t think about it anymore, it becomes part of us. We know what will happen when we move in a certain way without it being a conscious decision.

Action through an instrument becomes instinctual.

In the 1980s there was a famous study by Benjamin Libet, who through a series of EEG experiments showed that the brain “registers” the impulse to perform a movement before activity in the conscious decision region of the brain is present. (Taylor, 2019) Although it was later contested, this study was used by some theorists as proof that there is no such thing as free-will, since the body acts before the mind has time to understand.

We can also recognize that this reaction on instinct is an important part of instrumental performance practice, which aims to internalize the the nuances of action to perform through the mediation of the tool.

This expansion of intention through objects could potentially be traced back to the practices we developed as hunter-gathers. In her book, Challenger, writes about studies of the South African San people, one of the last remaining hunter-gather societies:

“What began to fascinate anthropologists who studied the San was their meticulous imitations of the animals they hunt. The hunters, in some sense, become animals in order to make inferences about how their prey might behave. This spills over into ritual. The San use hyperventilation and rhythmic movement to create states of altered consciousness as part of a shamanistic culture. In the final stages of a trance, Lewis-Williams writes, ‘people sometimes feel themselves to be turning into animals and undergoing other frightening or exalting transformations.’ For anthropologist Kim Hill, identifying and observing animals to eat and those to escape might merge into ‘a single process’ that sees animals as having humanlike intentions that ‘can influence and be influenced’. […] [H]umans are also mindshifters. Not only can we see other things in a single image, we can also see other minds in other things.” (Challenger, 2021)

So, the tools we use are an extension of ourselves, and evolved with us through social practice, developed over a million years. I would speculate that our relationship with things, is based on our social understanding that other things can be entities with their own agencies. Like relating to other people, relating to other things may also require some psychological ability to read the thoughts and agency of other nonhuman things.

For example, in this description of hunter-gatherer shamanic practices, the hunter-artist performs a transformation into the prey or predator, using their body and psychological energies as an instrument to help them to foresee the actions of the other animal through being them in some way.

Embodied learning, affordances and constraints

As we learn to influence and perform with a tool or object or entity, we are learning to understand its unique agency and character; how it responds when we interact in one way versus another.

In human-computer interaction (HCI), these are often referred to as the affordances and constraints of the system, which describe the ways certain types of actions are encouraged or discouraged by its design. (Gibson, 1977)

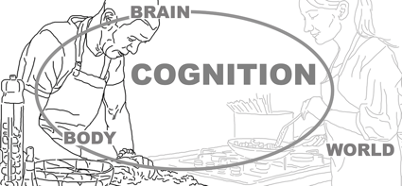

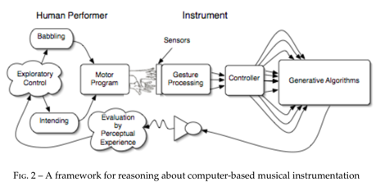

Based on the embodied mind perspective developed by Fransisco Varela and others, David Wessel refers to this process of instrumental learning as an enactive process which “emphasizes the role of sensory-motor engagement in musical experience,” towards the formation of a “human-instrument symbiosis.” Wessel goes on to discuss the process of learning through the action of babbling, named for the critical role of exploratory vocal experimentation in the development of speech in infants, as they learn to connect sounds with the physical process of production the sound. (Wessel, 2006)

One of my other mentors in instrument design was the late Joel Chadabe, who expressed a similar contextual perspective of learning through action, which he likened to “sailing on a stormy sea”, where the sailors have to adapt and learn how to balance and maybe even steer the ship as the waves and winds toss and turn around them.

This is a bottom-up approach, where knowledge is developed first through action, versus a top-down perspective where plans and ideas are constructed and then executed.

Improvising musicians are good examples of practitioners who are deeply involved with the generation of material from the human-object relationship. Derek Bailey writes:

“Although some improvisors imply a high level of technical skill in their playing, to speak of ‘mastering’ the instrument in improvisation is misleading. The instrument is not just a tool but an ally. It is not only a means to an end, it is a source of material, and technique for the improvisor is often an exploitation of the natural resources of the instrument.” (Bailey, 1975)

Let’s keep thinking through the history of this idea of instrumental agency.

In his book A Million Years of Music (2015), Musicologist Gary Tomlinson discusses some of the current theories of the social and cognitive context surrounding one of the oldest known tools of the Paleolithic era, the Acheulean biface.

The remarkable symmetries formed in these human shaped rocks, seem to imply a high level of planning to achieve this level of ornate detail. However, archeologies have determined that rather, these tools pre-date our modern conception of planning, and “thinking-at-a-distance.”

Tomlinson writes:

“Preconceptual action sequences are structured according to these material affordances, the energy required in working them, and the biomechanical limitations of the worker; and all these together can be enough to engender systematic patterns tending to produce material symmetries. From this vantage, thinking of the hominin mind dictating symmetries has it backwards; it is the body-stone interaction from which symmetries (and perhaps even the mind) emerge. The variability of raw materials, more than varied conceptual plans, will lead to variability in tools produced as well as varied embodied thought.

There is a rich and provocative opportunity glimpsed here of reversing our habits in conceiving early hominin experience. It is not that stone tools are proxies of mind but something closer to the reverse: mind as an outgrowth of the body-stone interface.” (Tomlinson, 2015)

And so here we confront a powerful idea: our conceptual development, which has driven humans’ evolution of tools as extensions and modes of expression, was possibly the result of an enactive performance practice, rather than a sudden flash of cognitive advancement.

Tomlinson continues:

“Such performative sociality requires little thinking-at-a-distance. It is closely related to conceptions of embodied cognition that resist the Cartesian separation of thought from matter and emphasize the situatedness of cognition in material matrices extending out from the body.” (Tomlinson, 2015)

So, as we move, exploring the material matrix that connects our bodies with our tools and environments, we are feeling our way through, and learning by trial and evaluation of the material, and forming a cognitive system, moving from the details toward higher level “thinking-at-a-distance.”

And so, when we perform with an instrument, we are in a way creating a new symbiotic body “material matrix”—a relational network, binding together an assemblage of objects and entities. Each element has its own character, ways of moving, affordances and constraints, and their own layers of agency in the process.

Body-instrument persona

Our bodies also internally function through the agency of many different lifeforms, incorporated bacterias, inherited virus DNA, etc. (Quammen, 2018) But yet our minds generally seem to produce a unified experience of the world. In a way, we might read our deep involvement with objects as an externalization of the this principle of symbiosis, where our minds subtly include other life and objects into our sense of self.

The history of human ritual and mysticism is full of examples of people finding ways to extend and access different parts of themselves through use of tools, like mask, costumes, painting, dance, and music, which are all processes which act to embody the subjective self into a expanded body-instrument persona.

The expansive experience of human-object symbiosis can also be a tool for fighting for agency in situations where the one’s physical body has been subjugated by an oppressive force, as addressed in feminist and critical race studies.

For example, the early Afrofuturist work of Sun Ra, Parliament Funkadelic, and later in the advent of hip-hop, beat-boxing, turntablism, and techno music.

Achille Mbembe writes:

‘Afrofuturism is not simply content on shattering the illusion of the “properly human.” Rather, according to them, the black experience defeats the very notion of the human species. Produced from a specific predatory history, the Black is essentially a human refashioned into a thing, forced to endure the same fate as that of an object or tool. Because of this, the Black has become bearer of a kind of human grave. He is a wraith who haunts the delirious fantasies of Western humanism, itself having become a kind of crypt to house the souls of all those forced to share the fate of objects.

With such a rereading in hand, the Afrofuturist movement declares humanism henceforth obsolete. If one wants to adequately grasp the contemporary condition—the Afrofuturists contend—one must do so from all the assemblages of human-objects and object-humans, for which, since the arrival of the modern era, the Black has been both prototype and prelude. For, once Blacks erupt onto the modern world scene, there is no longer a “human” who is not already enmeshed in the “non-human,” the “more than human,” the “beyond human,” or the “otherwise-than-human.” ’ (Mbembe, 2016)

And so, in this way the Afrofuturists and posthuman line of thought towards the “non-human” is a way of de-centering the “human” as defined by a culture of oppression.

Similarly, in critical ecology and animal studies, there is a effort to correct the unconscious anthropocentric bias that is encoded into almost all aspects of modern culture; working to counter the myth of human supremacy found in many religions, which, as Challenger discusses in depth, suggests to anthropocentric humanists that as a human, we are somehow superior to the other animals; and maybe we are not even animal? bur rather, maybe placed on earth by god as owners of the land.

Origins of logistics and data science

So our collaboration with objects and other nonhuman agencies has been a key factor in our evolution as a species, yet eventually there has been a tendency to work towards a reduction in the perceived agency in nonhuman things.

This bias of human exceptionalism and supremacy seems wrapped up with our instinct toward tribalism, which has helped our species defend against competing groups and predators, and also acted as a catalyst promoting strong social bonds and collaboration within a trusted group.

With the advent of agricultural techniques in around 10,000 BC humans increasingly applied a logic-based methodology to harvesting their food resources. (Harmon, 2009) Rather than an interactive encounter with nonhuman entities, where both participants are understood to have agency in the encounter, agriculture relies on strategical thinking that aims to domesticate the Other. The Other, then becomes further separated from ourselves and our tribe, until eventually humans deemed themselves somehow separate from the rest of the earth, forming the difference between “wild nature” and human society, and eventually to a form of human supremacy.

Timothy Morton speculates that this development of agricultural logistics acted to “sever” humans from the biosphere:

“What the Severing names is a trauma that some humans persist in reenacting on and among ourselves (and obviously on and among other lifeforms). The Severing is a foundational, dramatic fissure between, to put it in stark Lacanian terms, reality (the human-correlated world) and the real (ecological symbiosis of human and nonhuman parts of the biosphere). Since nonhumans compose our very bodies, it’s likely that the Severing has produced physical as well as psychic effects, scars of the rip between reality and the real. One thinks of the Platonic dichotomy of body and soul: the chariot and the charioteer, the chariot whose horses are always trying to pull away in another direction. The phenomenology of First Peoples points in this direction, but left thought hasn’t been looking that way, fearful of primitivism, a concept that inhibits thinking outside agrilogistic parameters” (Morton, 2017)

And so, the nature of this “agrilogistic” approach is a focus on isolation of parts, so that each element can be logically reasoned, and strategically organized. As we can clearly see in history, this is an extremely powerful way of thinking, and provided the basis for our eventual development of computational systems. However, when combined with biases of human, and cultural supremacy, the logistical approach can also lead to oppression and devastation; for example the histories of ecocide and slavery.

Returning to Achille Mbembe’s reflection on Afrofuturism, he writes:

‘The Afrofuturist repudiation of the modern notion of “Mankind” is nevertheless surprising. Does it not ultimately reinforce certain ways of thinking rooted in the flagrant denial of black humanity?

Let us not forget that since the start of the modern era we have dreamed of becoming masters and owners of ourselves and of nature. To achieve this, we needed to know ourselves, to know nature, and to know the world. From the end of the Seventeenth Century, it was thought that the best way to do this was to unify all domains of knowledge and to develop a science of order, of calculation, and of measurement that would facilitate the translation of natural and social processes into arithmetical formulas.

With algebra having become the means by which one models nature and life, a modality of knowledge has gradually been imposed that consists essentially in making the world flat, that is, to homogenize the entirety of all living things, rendering these objects interchangeable and manipulable at will. This process of flattening the world, spanning many centuries, has been the governing motivation behind a substantial part of modern knowledge and cognition.

This flattening movement has been accompanied, in various degrees and with incalculable consequences, by the other historical process typical of modern times, namely capitalism and the global zones created by capital. Since the Fifteenth Century, the Western Hemisphere has acted as the privileged engine of this new planetary venture, and it has been propelled throughout by a system of mercantilism and enslavement. On the basis of triangular trade, the entire Atlantic world was restructured; the great colonial empires of the Americas emerged and consolidated themselves, and thus began a new era of human history.’ (Mbembe, 2016)

Homogeneous data, Capitalism, Containerization

One concrete example of this homogenization process is discussed by Gavin Mueller, in his discussion of the impact of containerization in commercial shipping, He writes:

‘This was the impact of “containerization,” the technological standardization of shipping by enclosing all cargo into uniform metal crates. Containers were intermodal: creates could be loaded, by crane, directly onto or off of ships via trains and trucks. This meant the end of the laborious loading and unloading of cargo by hand, piece by piece[.]’ […]

‘Containerization completely upended the dock system. Not only were fewer dockworkers required for the containerized ports, but, by drastically reducing loading and unloading times, and therefore making the shipment of goods dramatically less expensive, fewer ports were needed; many cities, including New York, saw their waterfronts and their associated communities decimated in just a few years. But the revolution didn’t stop at the docks. As transportation of goods was no longer cost-prohibitive, manufacturing could be located wherever labor costs were lowest. It could be centralized, since there was little need to locate production closet to consumption. Containerization was the essential precondition for what has become known as as globalization, where production is scattered along far-flung international supply chains.’ […]

‘[…] containerization was not driven solely by industry needs for efficiency, but also by miliary order […]. Indeed, without containerization, Levinson argues that “America’s ability to prosecute a large-scale war halfway around the world would have been severely limited.” In fact, the Vietnam War was instrumental to early processes of globalization: after dropping their material in Da Nang, container ships stopped off in Japan to fill up with electronics before returning to the West Coast.’ (Mueller, 2021)

So after the process of containerization, the dock workers no longer knew what was inside the boxes. Their focus was shifted from managing the direct transfer of the content, to the mediated transfer of standardized containers.

And it is this same process of containerization that is the foundation of computational systems of data processing.

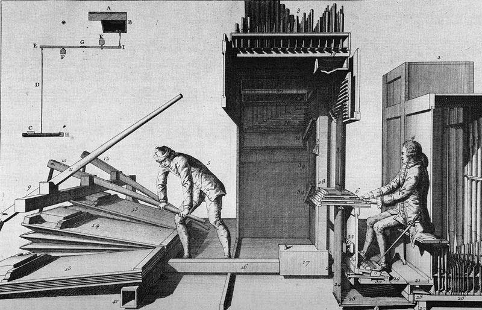

Shifting back to the musical perspective, we can trace some of the same types of technological abstraction in evolution of keyboard instruments. The keyboard is a homogenized interface that triggers a sequence of mechanical actions which combine to make the sound we hear. Organs for example are controlling wind pipes and reeds, whereas, harpsichords control a plucking mechanism, a clavichord pushes a metal blade gently into the string, and a piano has a striking and escapement mechanism; each keyboard instrument feels different to play, with different actions, and sense of weight to the keys, however they all share the same basic twelve note per octave keyboard design. In the late 19th century, it was therefore an easy transition to introduce electronics into organs, and other keyboard instruments. The keyboard and equal-tempered chromatic scale were the same, only the mechanism that performs the sound in response is changed.

Equal-Temperament itself is another example of homogenization which leads to increased modularity, e.g. the relative equivalence when transposing a chord from one key to another.

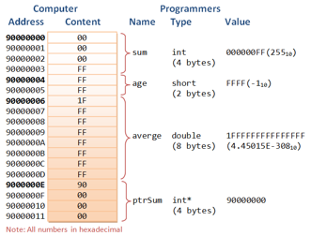

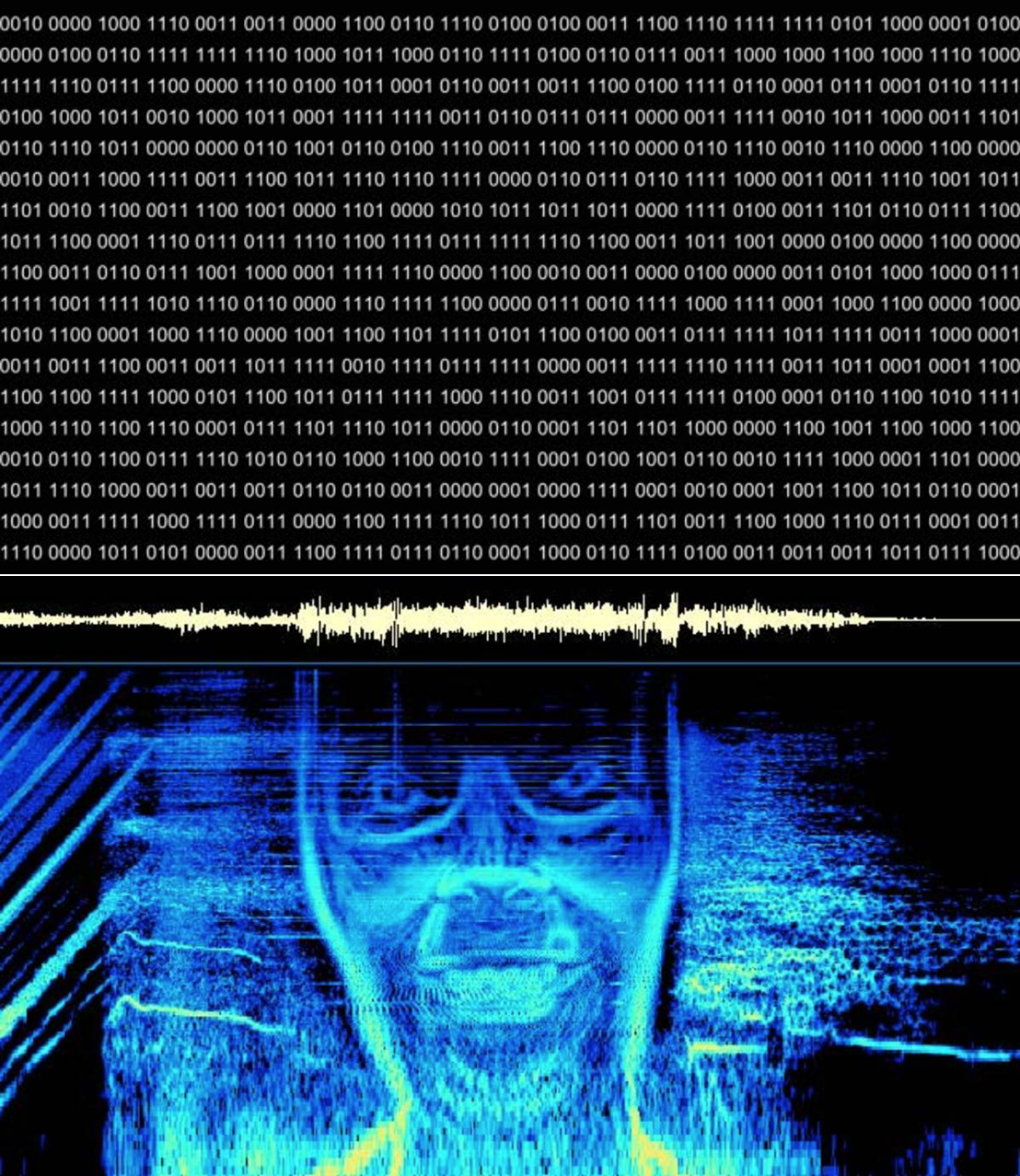

In the context of digital systems, this homogenization is taking even further. The input and output of the system, if human readable, will be some kind of sensory media (sound, image, touch, etc.), however, between the input and and output the signals are converted into binary data.

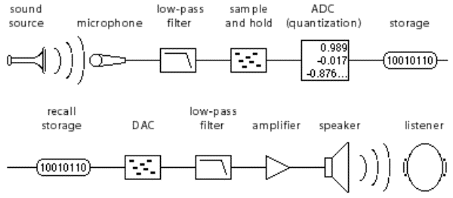

For example in digital signal processing, a microphone first translates sound pressure waves traveling through air into voltage fluctuations. The fluctuating voltage is then “digitized” by an analog-to-digital conversion, which reads the voltage values at regular intervals, and records the sequence of values as a series of numbers in a memory buffer.

Each byte of data is only a value, it has no context by itself. Once stored in memory, knowledge of what type of information is stored at a given memory location is required in order to give meaning to the data.

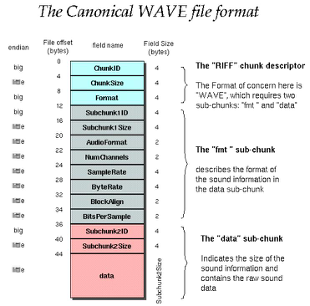

In a sound or image file, there is usually a header included which declares the type of the file, and other metadata regarding the contents. And so, in the computer, this context itself is also just another block of values, which also has to be read in a defined way; for instance using the file format extension code which is recognized by the operating system.

This characteristic flatness of data creates blurring of media boundaries. Similar to shipping containers, and the way in which a commercial synthesizer keyboard can switch from one sound to a completely different sound by selecting a new preset, gestures stored in data can just as easily be interpreted in a totally different media context (albeit with differences of aesthetic results). For example, the famous Apex Twin piece using MetaSynth to perform a photograph of a face as a frequency spectrum.

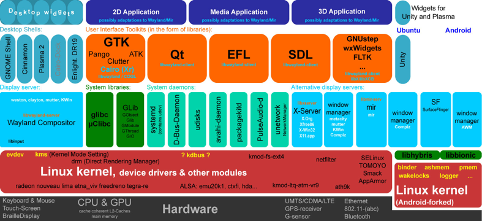

Within the world of data, the operating system functions as a virtual ecosystem, filled with daemons and WC3 specifications through which the data gains a definition of type, and clearly defined protocols for how the regions of data should be read and evaluated. The digital environment within the computer is purposefully abstracted, in a design that aims for maximum efficiency and computational flexibility through the polymorphic nature of homogenized storage containers.

I think it’s important also to remember that computers are at the lowest level still a physical system, shrunken to ever smaller dimensions, but really are not so different from a very complex synthesizer.

And also the history of computation is closely connected with musical instruments!

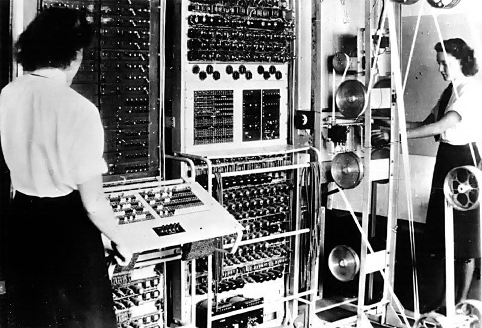

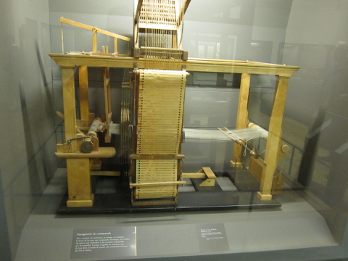

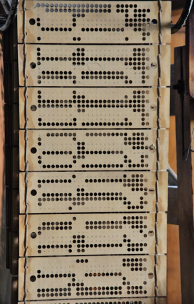

For example, some of the earliest forms of binary representation used for mechanical operations can be found in the hole-punch techniques used in the first mechanical looms, dating from 1725, developed by Basile Bouchon, the son of an organ maker.

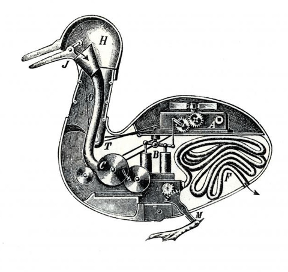

Later the mechanic loom was then further developed by Jacques de Vaucanson, who was famous for creating automata of a flute player, and a digesting duck.

The hole-punch system was then later modularized in the developments of Joseph-Marie Jacquard, who in 1804 patented a system that used interchangeable cards to create a sequence of threading patterns. (Science and Industry Museum, n.d.)

(Science and Industry Museum, n.d.)

(Science and Industry Museum, n.d.)

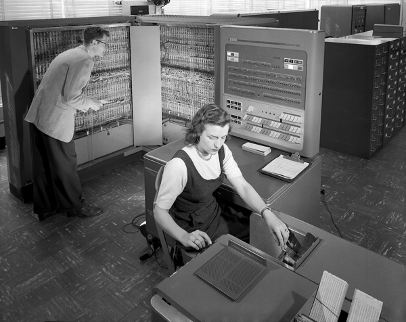

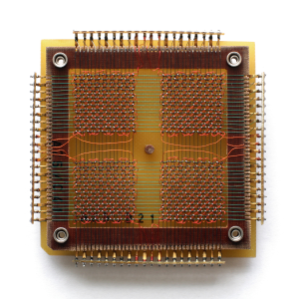

The punch card technology was later used for early computers, and developed into smaller and smaller form factors. In the 1950s through the 1970s, magnetic core memory was used.

(Science and Industry Museum, n.d.)

The Jacquard loom provided a fully automated mechanism which allowed for the creation of highly detailed textiles, reducing the required work with the machines to simple manual labor without need for any skill or expressivity. Having arrived just after the Napoleonic Wars, this further aggravated the struggling livelihood and culture of French silk weavers who “greeted the arrival of the Jacquard loom by attempting to assassinate its inventor and destroying the device publicly in Lyon.” (Mueller, 2021) .

The mechanism continued to spread however, and was a driving force in the industrial revolution, causing a major upheaval and devaluation of traditions of master weavers in the name of industrial production of capital which flowed upwards to the owners of the machines. Meanwhile, the skilled artisans where no longer needed, but rather low wage workers who were required only to manage the functioning of the machines, which resulted in the hollowing out of the middle class still visible today.

Encoding of knowledge

And so, the knowledge of how to move between different sequences of woven thread was encoded into a binary punch card representation, which was then performed by the mechanical looms. This is one of the first examples of what eventually became computer programming.

Like the automated loom system, a computer stores a sequence of instructions in an internal memory buffer which executes the shifting of bits in order to produce a desired outcome.

From an instrumental perspective, we can see that the more layers of mediation there are in a instrumental system, the more opportunity there is for the designer of the system to embed their own understanding, aesthetics, and desires into the tool’s inner working; and digital systems are particularly mediated systems. For example, in the digital signal processing figure above, notice how many stages there are with transform the data from one form to another.

As Thor Magnusson writes:

“The objects around us – the technologies that serve as props in our thinking and music making – are stuffed with people and their ideas; in them we find programmes of action, manuals of behaviour, and political and sociocultural constructions, including aesthetic tendencies.” (Magnusson, 2009)

I love this image of objects being “stuffed with people and their ideas.”

Thinking about this the other day, I took a walk in my neighborhood and suddenly started seeing the history in all of the objects around me. Each object has a backstory contained in it; that gives it its character. For example, a candy wrapper laying on the ground has already been through so much. The the raw materials, paper and wax, have their histories, and then the design of the wrapper to fit the candy, the machines that make the wrappers, the graphic designers, the kids choosing the candy at the store…

And so, when we are thinking about the forms and meaning of objects and instruments, we are also examining this embedding history and ideas about the nature of the object and how it might function in some social / physical contexts.

Instrument system components

Ok, so let’s take a closer look at what makes up an instrumental system, keeping these histories we’ve been discussing in mind.

And we will have to grapple with the interaction between these overlapping processes: the direct, enactive human-object relationship; and the mediated, top-down design process which embeds the designers ideas into the system.

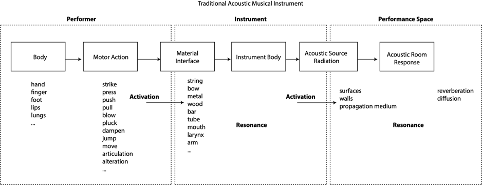

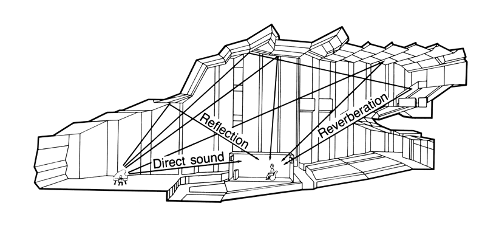

In a traditional acoustic musical instrument, there is a performer, the instrument, and the acoustic, as well as social spaces where performance takes place, since, as we have learned, all instruments are situated in a context.

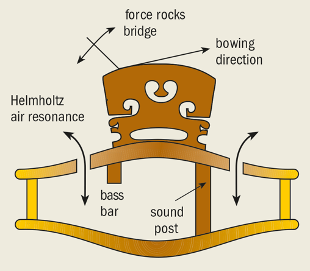

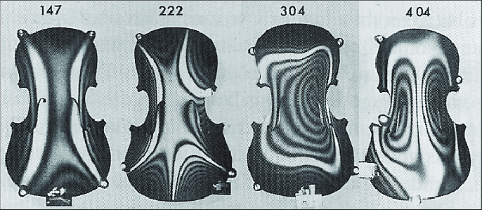

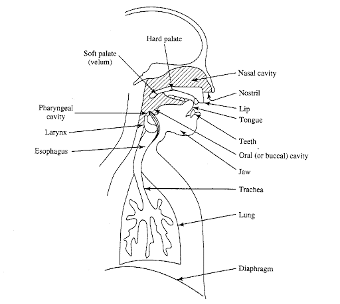

To perform a note on a musical instrument, the performer uses their body to interface with some element of the instrument construction. On a violin, this might mean with the right arm, hand, and wrist, drawing a long strand of rosined horsehair across a wound metal string causing it to vibrate, while pressing the fingers of the left hand downwards on the string, so that the vibrational length of the string is shortened, which changes the pitch. The vibration of the string is transferred through the bridge and sound post, to the body of the instrument which resonates, amplifies, and transfers the string vibration to the various surfaces of the instrument, which in turn transfer the vibration to air pressure waves, which radiate outwards spherically from the instruments into the space.

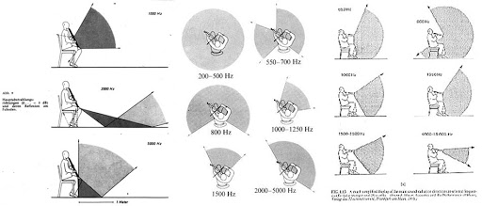

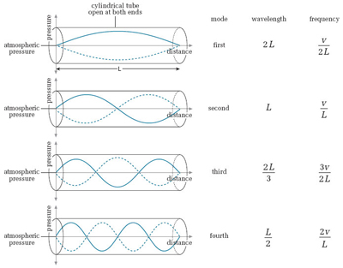

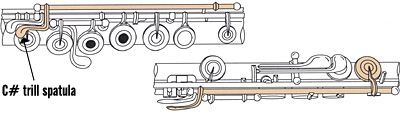

Each type of instrument has different modes of activation, resonance, and vibration which give it its characteristic timbre—and the different materials and manners of interaction, give each instrument a unique tactile character, which influences the performance and interaction. For example, a metal string pressed into the finger tips is a very different experience from pressing a smooth key of a flute; and also there is a big difference in experience between using the lungs and lips to shape air flow to vibrate a column of air, from using a bow to vibrate a string.

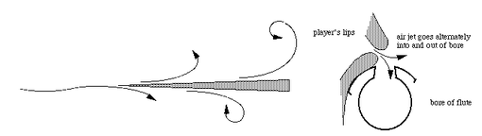

Here we can also see the affordances of these different performance techniques. For example, the nature of the wind and embouchure techniques required to make a tone on a flute, contains an affordance for highly nuanced variations over the duration of the tone. Drawing on the mechanism used in vocal performances of speech and signing, flutists control the speed of air flow, and shape of air resonance in the mouth though manipulating the tongue and embouchure. As a note is sustained on the flute, the instrument provides an interface between the wind control system of the body and a way of vibrating a column of air in a resonant tube. The key mechanism of the flute provides other affordances, for example, the spring action of keys afford rapid trill figures.

A constraint of the flute, is that you have to hold it is a certain way, and focus the air flow in the right way to trigger the vibration in the air column.

An affordance of the violin, is that you can play more than one note at a time, since there are more than one string, whereas, this is a constraint of wind instruments in the traditional sense (ignoring multiphonics for now). Another affordance of the violin is the smooth shifting between notes, since there are no frets the finger can slide along the strings to create glissandos.

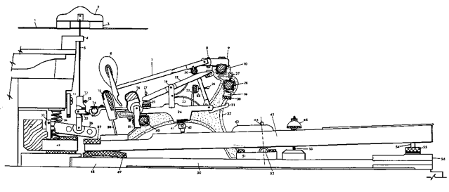

The key and valve mechanisms of wind and brass instruments are some early technologies for expanding the range of the instruments. However, in the development of keyboard instruments we start to see an even more extreme process of mediation in instrument design.

In keyboard instrument designs like the organ, harpsichord, piano etc., the keys act to trigger a secondary action, which performs the actual physical activation. The performer then no longer needs to know about, or directly manage, the mechanical activation and resonance of the instrument, but rather should focus on the technique of pressing the fingers down on the right keys at the right time; the mechanics of the instrument take care of the rest.

This abstraction has some powerful affordances. As we have seen, if this type of design is applied within the framework of colonial capitalism it can have a devastating effect of people’s lives. Inside a piano, the effect is more contained, effecting only felt and metal wires. However, the point is that these ideas are not separate, but are a basic application of the same logistical approach to design. In the current era of computational everything-ness, the line tends be blurred at the boundaries between which types of design are harmless and which act to constrain the life of the users of the systems.

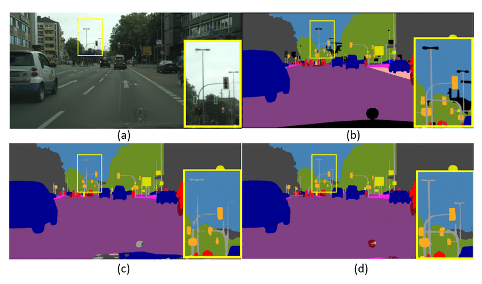

By the way, did you that when you identify elements in a ReCaptcha, “I’m not a bot” test, that you are actually working for Google? They realized that rather than having you type in some hand written digits, as in the original Captchas (which stands for Completely Automated Public Turing Test To Tell Computers and Humans Apart), Google realized that they could use the public as unpaid workers to produce semantic image labeling masks.(Mueller, 2021) (Olson, 2008)

So, the point to keep in mind here is that any design, like the architecture of a building, has an effect on the people using it. And that, in instrumental contexts that integrate mechanical and computational processes, the design process results in an increased agency of the engineer in the process.

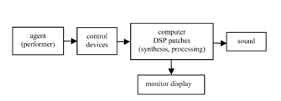

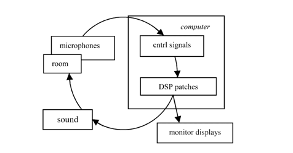

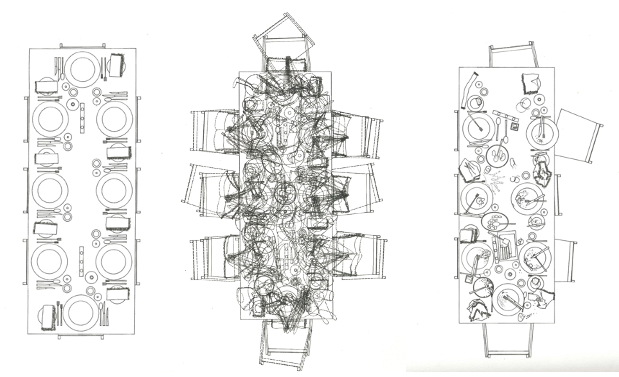

Shifting back to musical instruments, here is a diagram borrowed from Agostino di Scipio, outlining the basic flow of an interactive music system. (Di Scipio, 2003) The diagram is centered on digital music systems, however, I think it is equally applicable to mechanical systems like the piano, and organ.

As in mechanical systems, computational instrument systems function through a mediation between the interaction interface, and the media production, which in the case of music is sound, but in multimedia contexts the output could also be other media. The performer interacts with some kind of sensing device, which converts the gesture information into voltage which is then sampled and quantized, to produce normalized data which can be interpreted by the computer.

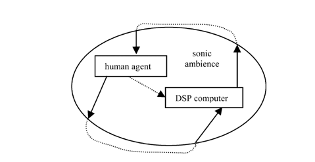

Like Wessel, Di Scipio also follows Varela in an enactive approach to instrument design, emphasizing the cybernetic feedback loop which includes the performer’s re-evaluation of the output of the systems as well as the acoustic environment which situates the interactions.

And so, the performer is in a feedback loop, acting and reacting within a system of agencies including the affordances and constraints of the physical interfaces, as well as those of the mechanism of the computational part of the system. The computational logic is embedded into the system, in an act of composition, which encodes the aesthetics, knowledge and biases of the author, who makes assumptions and predictions about the future interactions of the system performed by the instrumentalist.

In many ways, we can also draw parallels to the work of John Cage and Morton Feldman here who developed open and semi-open forms of composition which function to control certain parameters of performance while leaving others open to other agencies.

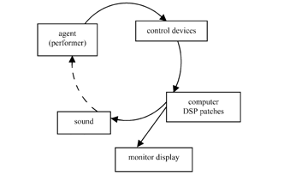

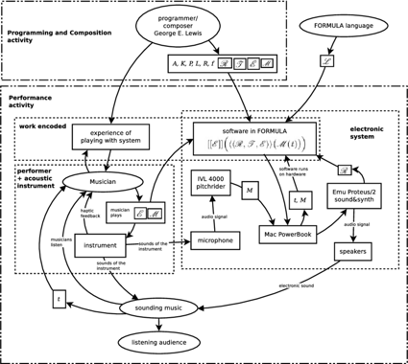

David Wessel’s variation on the instrument system design model further illustrates the role of the human performer in the feedback loop. Implied also in Wessel’s diagram, is a mirroring action of the generative algorithm with the human performer’s cognitive process of enactive learning. The computational algorithm responds to the gesture input through a process of interpretation that connects with programmed expectations of the types of gesture that it might receive, based on the human programmer’s own set of enactive experiences.

Computer assisted performance/composition

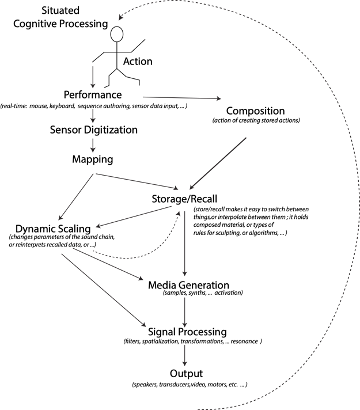

For the Situated Instrument Design class, I also made a variation of Wessel’s diagram, which introduced some more details showing the flow of the data within the computational block of the instrument system. I also added the process of composition into the model.

The instrument system depicted here, is what Joel Chadabe used to call a composed instrument. As high performance personal computers became wide availability, artists have gradually gained a higher degree of programming fluency, and more and more are able to implement the designs of instrument programs themselves, which previously required an specialist engineer who would mediate the ideas of the artist. (Schnell et al., 2002)

Considering “composition” itself as being a performative action—an action of creating later actions—we can see at least two layers of composition in the system. First is the act of composing the framework of the system as an instrument for computer-assisted-performance, which creates or manipulates media in response to the performer’s actions.

The second order of composition can occur when the system also provides tools for the user to compose presets or customized mappings. In this case the system might be considered as a tool for computer-assisted-composition, for example a software platform that provides the user with tools that produce new musical sequences based on the values set by a graphic user interface, for example in a DAW, or using a generative process for producing material. And so, a computer assisted composition system is itself a kind of instrument that the composer performs with which produces some kind of score-like media.

And here again there is a strong influence of the design of the system in the possible outcomes that the user is able to produce; the affordances and constraints of the system. For example, a music notation program that requires the user to specify a rhythmic meter, forces the user to think in terms of rhythmic subdivisions, and so on.

Thinking of composition as a performance practice, we can also look again to Cage, Feldman and Earle Brown (and many others) who used paper as an instrument of compositional performance. For example Brown’s graphic scores, Cage’s Music for Piano 1, where he used of the imperfections of a sheet of paper for positions of musical events, (Cagney, 2021) or Feldman’s practice of setting up a perfect grid of measures on each page and writing with ink from the beginning. (Feldman, 2000)

Importance of context, distributed agency

Further, in the case of participatory art, or what Nicolas Bourriaud refers to as “relational asthetics” (Bourriaud et al., 2002) , we might also consider an instrumental system which functions in a framework of social interaction, where the “media” includes the interaction of the participants rather than only the media that the audience experiences.

For example, the acoustics of a room will have a strong effect on the way people talk to each other, as they adapt their voices to be heard, or less heard depending on the rooms reverberation and level of speech intelligibility. In this way, an artist might “instrumentalize” the acoustics of the space to shape the experience of the visitors. And so the architectural and ambient elements that construct the context around an artwork are have a clear agency in the audiences’ experience of the work.

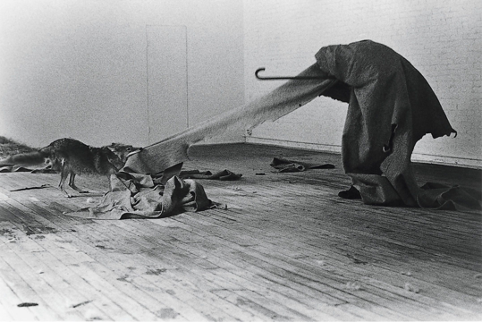

The inclusion of other agencies into artwork can also be seen in works that involve animals, for example Joseph Beuy’s famous piece where he locked himself in a room with a wild coyote, and the works of Robin Meier who works with a variety of animals and insects, for example his work with Ali Momeni, where they glued mosquitoes to microphones (in a non-harmful way) and played them vocal music, which the mosquitoes interpreted as a potential mate and tuned their buzzing to match in pitch.

In these cases the definition of “instrument” is maybe problematic. Is an animal a media? Rather, I think of these pieces as relational works that combine the agency of humans and nonhumans.

Computational agents

Through the programming of complex, multilayered, and non-linear interactions, computational systems can sometimes be understood as acting on their own. Rather than functioning as an extension of the human performer, the relationship to the human is as a meeting of individual entities. The aesthetic and behavioral knowledge has been composed into the system, and then is considered as a separate personality, acting with its own computational agency.

George Lewis describes his work with AI improvisation systems in this way:

“In Voyager, the computer system is not an instrument, and therefore cannot be controlled by a performer. Rather, the system is a multi-instrumental player with its own instruments.[…] In this sense it is useful to consider Robert Rowe’s taxonomy of ‘player’ and ‘instrument’ paradigms […], although I regard the two models of interactive role construction, not as a fixed binary opposition, but as a continuum along which a particular system’s computer-human interaction can be located.” (Lewis et al., 1999)

And so we can see that in some cases, the system built with the knowledge and skill of its designer encoded into its inner functioning, with unpredictable or non-linear mappings, might shift categories. No longer a tool to be controlled, it rather becomes an entity in itself, who acts with a higher level of agency in its interaction with other agencies.

Puppetry and strong AI

This idea of composing a system as a character who performs a role also has a connection with automata, and strong AI.

From the perspective of the human-object relationship, we can still view the creation of an autonomous performance system as an extension of the creator’s imagination of how this character might act and interact with others and its environment. And similarly, in a instrument system, the performer works in collaboration with the object, extending the performer’s sense of self. As they learn to perform with the system it becomes more and more natural, and second nature, to coordinate their gestures in connection with the media output.

In both cases, there is this process of creating a sense of character, a persona, that is closely related to the practice of puppetry, where there is a rich tradition of human/nonhuman symbiosis.

In terms of multimedia, I think of puppetry as the basic principle of mechanical and computational systems that produce media through this collaborative interaction with a performer. This can also take for form of a digital or mechanical performance, for example works of Jean Tinguely, László Moholy-Nagy.

Mapping strategies

While in an acoustic musical instrument, there is generally a more direct connection between the actions of the performer and the physical vibrations of the instrument body, in the context of computational instruments, the performer is interacting with a system of mediated actions.

And so the compositional process of instrument design focuses largely on the mapping of information from the input context to the output context.

What kinds of media performance should result from a given data input? How do the perpetual qualities of the sensing interface relate to the perpetual qualities of the output media? How should the audience read the relationship between the gesture and the resulting performance? What kind of experience does the performer have with their instrument? And related: How does the design of the system effect the types of expression that are possible?

By composing the mediation, we are also building the affordances of the system, which in turn form the possible relationships that the performer might develop with the instrument.

Thinking then from the audience’s perspective, we can view the design of an instrument system through the relationship that forms between the performative actions and the resulting media that is created.

Audio-visual relationships

To consider the relationship between sound and image, we can maybe take a quick look at some of the discussion surrounding the use of sound in early cinema.

As synchronized sound playback technology became usable, filmmakers like Sergei Eisenstein began to think critically about how sound influences the art of visual storytelling tools of editing and linear narrative. (Einsenstein, 1949)

This is a huge topic which we don’t have time to go into very deeply, but greatly simplifying we can focus on the problem of perceived “inner speech” of a character on screen as intuited by the audience, versus the “outer speech” of synchronized sound, creating a sense of realistic speaking of the characters which requires different, and possibly less active engagement of the audience. (Pudovkin, 1985)

One of the most despised approaches in early sound cinema was “Micky Mousing,” where the musical accompaniment is composed to directly correlate with the movements on the screen.

This direct correlation creates an audible, obviousness to the relationship between sound and image, which due to its highly literal orientation, has an effect of disrupts the flow of the narrative, in a more slap-stick kind of way.

“Nothing, it seems to me, can be more vulgar than musical synchronism in films. It is, again a pleonasm. A kind of glue where everything gets stuck rigid, and where no play (in the sense of ‘play’ in wood) is possible.” — Jean Cocteau (Cocteau, 1985)

However, even though there are many examples of filmmakers criticizing the redundant use of music to amplify a visual movement, as cinema continued to develop into the sound age it did begin to incorporate the use of environmental and sound effects established in the context of radio plays starting in the 1920s.

In the cinematic sound practice of the Foley Artist, artificial sounds are created in the studio, and synchronized with visual movement in order to create a sense of realism in the scene. For example, in many films, there are continuous audio tracks added to most scenes to fill in the sounds of doors, footsteps, and fabric moving with the characters on screen which gives a the scene a sense of naturalism. The foley artist creates representational relationships of sound to the objects and actions on screen.

In Mickey Mousing, on the other hand, motions on screen are depicted in the form of musical sound which function within the framework of abstract musical structures of pitch-hight and rhythm. And so through this process of abstraction from the actions on screen, the musical representation has an effect of flattening the meaning of the image.

Sounds in the real world are produced by the interaction of physical objects, and spaces.

So, in the case of representational sound (as in the Monty Python and Fischli & Weiss examples), the sound acts to reinforce of the natural physical event, while an abstracted sound acts to re-contextualize the event, from the natural impression into a musical space.

Though his experiments with tape recordings, Pierre Schaeffer’s development of musique concrete explored this tension between the representational and abstracted processes in sound. For example, similar to some principles of Montage theory, Schaeffer studied the importance of the attack transient on our ability to recognize the source of a given sound, produced acoustically by its characteristic relationship between physical objects.

By removing the initial moments of a sound and fading into the resonant, continuation period, Schaeffer was able to abstract the sound from its source, and through recombination could mask the identity of one sound, using the transient of another source.

Tape recorders also provided the possibility to shift the pitch of the sound by changing the playback speed, further altering its representational meaning.

Representational instruments

In the context of mediated instruments, this representational aspect of sounds also plays a large role. In many electronic and digital instrument systems, there is a skeuomorphic process at work, where the instruments sound synthesis process is designed to produce the sound of another familiar instrument.

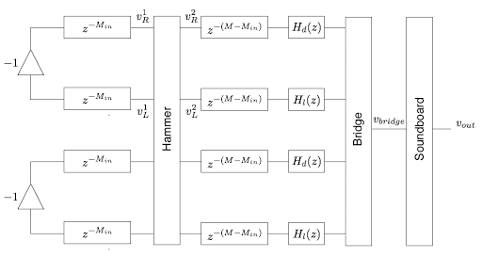

For example, when designing an electric piano the electronics will usually be designed to produce the characteristic attack-sustain-decay amplitude envelope of an acoustic piano. In a digital signal processing context, this might be through the use of physical modeling, which mimics the activation and resonance processes in a physical system.

Glitch and meta-systems — and object realism

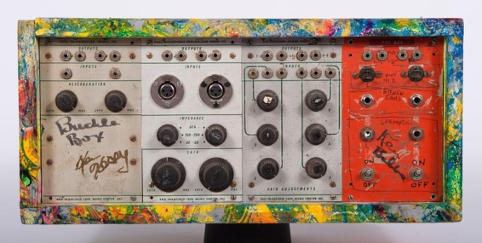

As digital technologies were becoming dominant in the 1980s and 90s, an aesthetic of glitch music emerged through the work of experimental musicians like Yasunao Tone, Nicolas Collins, and the band Oval who used skipping CDs as sound materials. In the work of these artists, system malfunction become the voice of the instrument. Working in a similar vein as artists like Christian Marclay, who created loops with skipping and sliced vinyl records, the sounds used by Tone and Oval’s skipping CD players is a distinctly digital flavor of malfunction.

Through this focus on system malfunction, glitch foregrounds the material-body of the system itself.

A typical commercially produced technology is designed as in a top-down process, functioning to produce some target result, while hiding the actual structure of the system out of the user’s view. When the inside is purposefully inaccessible or unreadable, we call it a “black-box.”

For example, a CD player is designed to spin a compact disc at a certain speed, and uses a laser data sensor to read the bits of audio sample data encoded on the surface of the CD. The sample values are stored in a digital buffer, and then an internal clock is used to perform the sample data at a given sample rate, sending the sample values through a digital to analog converter, which converts the data to voltage fluctuations, eventually becoming sounds, when the voltage fluctuations are converted to sound waves by the speaker transducers.

But of course usually no-one is thinking about this sequence of actions when listening to a CD: we’re listening to the sounds, just like turning on the radio, or playing a vinyl LP. The technological system that is in play in these three cases are all totally different, but the user experience is quite similar.

So, by causing the read head of the CD player to skip, these artists intervened into the physical action of the system. No longer do we hear the sample data in sequence to produce the sounds as intended by the makers of the CD, but rather the disruption causes the system to reassemble the information on the disk into a new sequence. This starts to shift our attention away from the encoded content of the CD, and instead to the process of the CD player’s buffering algorithm.

And so glitch can be thought of as a technique of producing real sounds that are embodied by material system that produces them, rather than a reproduction of abstracted or representational sounds.

This is a very reflective, enactive approach, which has the effect of fracturing the illusion created by the media system—a kind of Luddite action that widens the experience of the media to also include the details of the system that produces it; and potentially the assumptions and biases encoded into the system by its designers.

We can connect these ideas also with earlier works, for example the Duchamp ready-made, and in particular the work of John Cage, for example the works for prepared piano.

In each case, glitch creates a kind of second order, conceptual, meta-system that shifts from a focus on the products of the system to artifacts created by the design and construction.

In the visual domain, we can see similar approaches in Nam June Paik’s Magnet TV (1965) where he used a magnet to disrupt the functioning of a television, and Joan Jonas’ Vertical Roll (1972) where she used the rhythmic shifting created by an usually incorrect setting of the television’s vertical-hold circuit as part of the framework for her piece.

Another good example is Jimi Hendrix’s use of feedback, and the experimental electronics of David Tudor and Don Buchla.

This increased awareness of the larger systems at play was everywhere in the 1960s and 70s, and was a major driving force the counterculture movements.

Glitch seems to take two main approaches, either disrupting part of a functional black-box system, like Hendrix’s use of high gain amplification, or Paik’s Magnet TV; or working a bottom-up, structural approach, interacting with the inner workings of the system directly.

For example, we can see this structural approach in works like Tony Conrad’s The Flicker (1966) which used the alternating frames of film projection technology as a instrument for a kind of retinal music, and Iannis Xenakis’ S.709 (1994), where he uses dynamic stochastic synthesis techniques to directly generate sample data.

Sachiko M’s work with sampler test tones and extreme frequency ranges, is another good example of shifting the focus of listening and experience from a virtual space of artificial narrative, towards a realist material experience of digitally and boundaries of physical perception.

So, each instrument system has its own character, with its own set of affordances, and ways of malfunctioning due to its construction.

By studying the results of artifacts of system malfunction, we can learn how the system represents itself. For example a digital system can be represented with extremely accurate rhythms, exact repetitions, extremely short notes, precisely tuned frequencies, aliasing due to the Nyquist sampling frequency, and the ubiquitous frequency-domain compression garbling noise.

While glitch is often associated with computational and mechanical technology, the work of artists like Milford Graves and Keith Rowe similarly deconstruct the instrument using artifacts of the systems as artistic materials. And of course the work of musique concrete instrumental composers like Lachmann and Sciarrino.

Similarly, we could view the long-form works of La Monte Young, Morton Feldman, and Charlemagne Palestine as durational glitches of the listening experience, which work by shifting the listener’s perspective to larger sculptural systems of space, and emergent psychoacoustics.

The developments of Fluxus, happenings, installation, performance and conceptual art were all ways of expanding the perceptual frame of the artwork to include the surrounding context, reflecting on the system of production as part of the work itself.

Tactile listening, texture space

Thinking back to sound:

Glitches, mistakes, artifacts, and non-standard methods of performing on instruments tend to produce “noisy” and “complex” sounds which have a high degree of contrapuntal components within the sound; since the performance actions are no longer in accordance with the design of the instrument—most commonly designed to produce, clean idealized tones for the performance of western classical music. Instead, the modes of vibration and resonance are altered by the performer, and so rather than foreground the top-down performance of pure tones, the system vibrates in an alternative orientation.

From an artistic point of view, I find that I am almost always firstly focused on the timbre and texture of a sound that I am working with, and drawing the motive phrasing from a perspective of tactile listening. Is the sound smooth, or rough? Spiky, with sudden, rhythmic increasing and decreasing of volume? or more consistent, flowing in texture? Are there clearly defined layers to the sound? For example, a slow moving, low rumbling with higher sporadically moving frequencies above? Is it a dry, or liquid sound? Hot or cold?

And so, what I think of tactile listening is a kind of focus on the feeling of the texture, and finding the rhythmic and motivic possibilities that are there in the sound, in a very enactive, embodied, bottom-up way.

I started consciously thinking about this idea in 2012, when I was in residence at Ircam for a year to study the usage of Wave Field Synthesis (WFS) and Higher Order Ambisonics (HOA) as instrumental systems. One of the key realizations I had while working with these systems was that I would often spend a long time making beautiful distributions of sources moving through the space in different groupings and dynamic transformations; but then at some point, I would have to ask myself, “Ok, so, what sound should play through this spatial distribution?” And what I found was that the texture and psychoacoustic properties of the sound that you play through a spatial distribution has a huge effect on the perceptual experience.

So, what I learned to do with the systems at Ircam was to use this kind of tactile listening to find perceptual connections between the texture of sound and the spatial texture performed by the WFS and HOA.

What I found very useful was to relate my experience of tactile listening with David Wessel’s work on timbre-space (Wessel, 1979), and David Huron’s texture-space (Huron, 1989); using 2D plots to show relationships between perceptual factors, and begins to look something like a sound artist’s palette.

During the process of working on a piece for solo cello and live electronics with the WFS and HOA systems, I found that I could make textural connections between the different sounds I was using in the piece, with similar textures of spatial rendering techniques, which seemed to mutually enhance the character of the spatial l rendering with the character of the sound that the fed the rendering (Carpentier, 2016).

Later when reflecting on the composition process, I made a similar texture-timbre space plots to visualize the connections between the sound and spatial processes in the palette I had developed for the piece.

And I have continued to work with this feeling of tactile listening in more recent pieces, using this connection between different types of texture as a method of solidifying the relationship between spatial and sonic elements in an effort to create cohesive bodies and holistic atmospheres.

This connection between spatial and sonic form is also very related to the idea of puppetry, where the puppeteer works to create a sense of living entity, by relating the voice of the character with the movements of a sculptural form. Unlike natural sounding bodies, the puppet’s voice is usually physically separated from its body. In classical puppetry the puppeteers are usually hidden, and then synchronize their voices to speak at the same time as the puppet moves its mouth. As in theater, the voice of the character gives us information about who they are, and the puppeteer’s performance through the object, the audience is able to read the feelings and story of the character. Puppetry is in a way one of the oldest forms of multimedia instrument design, and when done well creates a strong sense of human-object symbiosis.

Recent work with video puppet instruments

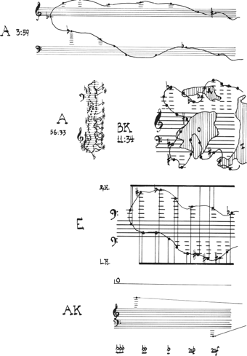

In a series of recent works, Apophänie, Scenes from the Plastisphere, and a new piece Animism which will be premiered later this year, I have been working with the development of video puppet instruments, which fuse digital and organic bodies as a way of attempting to create new connections between humans and non-human experience.

In the situation constructed by the instrument system, the performers use their hands (usually hidden from view) to manipulate objects and organic textures, viewed through a high-magnification macro-lens and live video capture. When projected to large scale, the miniature details of the organic textures seem to become all different kind of strange animals, plants, or more abstract materials of liquids or lab-like environments.

The video image stream is then analyzed by a computer vision algorithm which outputs various information about the image as interpreted by the different algorithms. For example, the speed of motion of an object, or its morphological character, size, orientation, and the quality of its contour, jagged or rounded, color, and so on.

While composing for this context, I generally first experiment with different physical materials and see how different types of movement and texture work on the screen. Trying different angles of light, different camera framings, and improvising with the material, feeling which ways of movement in the scene have the most control or expressivity, and studying the resulting scene for traces of characters that might emerge from the movements, and environments.

I should add that I mean “character” here in the most open way possible. In some cases the “character” of the scene, is a landscape for instance. Or a crumpled up piece of fibers paper sitting in a shallow pool of water that slowly absorbs water from underneath changing the paper’s shape like a time lapse video. Or perhaps the “character” of a scene is the physical presence of the screen itself, or the movement of the camera or lights might be the character.

After developing a character scenario, I will usually work out what kinds of actions will happen on the screen—potentially bringing in plot narratives, or symbolic transformation—based on the possibilities of the physical materials, camera and lighting.

In many cases, I’m working with very organic, hard to control materials, and so the composition of the actions tends towards a kind of framed aleatoric approach, where many details of the action are unspecified, but rather defined by more general performative description. For instance, a twisted mass of wire reaching out towards the camera, creates a kind of crab or spider-like gesture, however I leave the exact actions for the performers to figure out since the exact positions of the wires will be a bit different each time.

Once I have the sequence of actions figured out, I will generally break the sequence into scenes, and try to find effective computer vision analysis approaches that would make sense for textures and scenic context for each scenes.

For example, in scenes with a solid white or black background, it is easy to isolate a shapes in the image from the background, whereas in a scene in a highly detailed environment, it requires either some kind of background subtraction pre-processing, or using another approach like optical flow to separate the performed object from the background.

After finding a computer vision analysis approach that connects with the motion and scenic material, I then develop the “voice” of the characters by mapping the computer vision analysis to various digitally controlled sound processes.

Since by nature, the camera instrument is a highly mediated system, the relationship between the sound and image becomes very important. Loosely drawing on the ideas of foley, I will often study my perceptual experience of following tactile qualities of the objects on the screen, and try to identify what expectations I might have about the kinds of sound an object might make in the real world.

Often, I will make use of glitch type approaches in order to create sounds that reinforce to these intuitive experiences of haptic texture, in connection with a feeling of digital embodiment within the objects.

And so through this tactile listening approach, I try to create a kind of realism between the experience of the object and its sound produced by the digital system.

Meanwhile, the human performers are working to form a close relationships with the objects and their actions captured by the cameras.

Part of the performance practice of the pieces, is that the instrumental/puppeteers have to look deeply at the action on the screen, and adjust their physical movement to emphasize the characters they see there, and then as they attune to the character, it speaks through the computer.

So, there is kind of projection of feeling from the puppeteer into the object’s body, producing a multilayered experience: the performer feels themself acting through the objects, but at the same time tries to feel from the prospective of the object, creating an extended body between them; and similarly, the computer is studying the object and uses its composed/embedded knowledge to connect sounds with the analysis of the object from the video feed. Because the materials are organic and not totally controllable, the performer must constantly be engaged, and adapt to the agency of the physical materials.

And so the piece is a kind of an ecological minded attempt to de-center the human as the primary subject of performance, and instead tilts the focus towards the object, and the larger context of human-nonhuman interaction and symbiosis. One of the goals of these pieces, which is potentially unattainable, is that somehow, by bringing the attention towards the nonhuman actors, that the audience will have a greater sense of connection and empathy with the Other, human and nonhuman entities that are all around us everywhere. Since, ethically speaking, this subconscious biases of human exceptionalism, cultural supremacy and tribalism have caused so much damage to other lives and the planet’s biosphere.

The hope is that people will experiences some sense of opening in this tendency towards self-protection and defensive isolation. As Timothy Morton writes:

“Worlds are perforated and permeable, which is a way we can share them. Entities don’t behave exactly as their accessor wants them to behave, since no access mode will completely shrink-wrap them. So, worlds must be full of holes. Worlds malfunction intrinsically.” (Morton, 2017)

Conclusion

In conclusion, I would like to read a quote from Antonin Artaud, who was deeply thinking about the human-object relationship:

“Once aware of this language in space, language of sounds, cries, lights, onomatopoeia, the theater must organize it into veritable hieroglyphs, with the help of characters and objects, and make use of their symbolism and interconnections in relation to all organs and on all levels.

The question, then, for the theater, is to create a metaphysics of speech, gesture, and expression, in order to rescue it from its servitude to psychology and “human interest.” But all this can be of no use unless behind such an effort there is some kind of real metaphysical inclination, an appeal to certain unhabitual ideas, which by their very nature cannot be limited or even formally depicted. These ideas which touch on Creation, Becoming, and Chaos, are all of a cosmic order and furnish a primary notion of a domain from which the theater is now entirely alien. They are able to create a kind of passionate equation between Man, Society, Nature, and Objects.” (Artaud, 2018)

References

- Lexico. “Oxford Dictionary”. Retrieved 2021. 2021.

- Challenger, M. “How to Be Animal: A New History of What it Means to Be Human”. Penguin Books. 2021.

- McLuhan, M. “Understanding media: the extensions of man”. McGraw-Hill. 1964.

- Taylor, S. “How a Flawed Experiment ‘Proved’ That Free Will Doesn’t Exist”. Scientific American Blog Network, Scientific American. 2019.

- Gibson, J. J. “The concept of affordances”. Perceiving, acting, and knowing 1. 1977.

- Wessel, D. “An enactive approach to computer music performance”. Le Feedback dans la Creation Musical, Lyon, France: 93-98.. 2006.

- Hummels, C. & Dijk, J. “Seven Principles to Design for Embodied Sensemaking”. TEI 2015 - Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction. 2015.

- Bailey, D. “Improvisation”. Ampersand. 1975.

- Tomlinson, G. “A million years of music: The emergence of human modernity”. MIT Press. 2015.

- Beyene, Y. & Shigehiro, K. & WoldeGabriel, G. & Hart, W. K. & Uto, K. & Sudo, M. & Kondo, M. “The characteristics and chronology of the earliest Acheulean at Konso, Ethiopia”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, no. 5: 1584-1591. 2013.

- Sibbald, S. J. & Eme, L. & Archibald, J. M. & Roger, A. J. “Lateral gene transfer mechanisms and pan-genomes in eukaryotes”. Trends in Parasitology. 2020.

- Quammen, D. “The tangled tree: a radical new history of life”. Simon and Schuster. 2018.

- Mbembe, A. “Politiques de l’inimitié”. La Découverte (pp. 146-151.) Translation by Galloway, Alexander. 2016.

- Harmon, K. “Humans feasting on grains for at least 100,000 years”. Scientific American Blog Network, Scientific American. 2009.

- Morton, T. “Humankind: Solidarity with non-human people”. Verso Books. 2017.

- Mueller, G. “Breaking Things at Work: The Luddites are Right about why You Hate Your Job”. Verso Books. 2021.

- Science and Industry Museum. “The story of the Jacquard loom. Science and Industry Museum”. Science and Industry Museum, Retrieved September 20, 2021. n.d..

- Cortuk, D. “C++ Pointers”. Retrieved 20 September 2021. 2020.

- Steyerl, H. “STRIKE”. 2010, 28s, HDV. 2010.

- Magnusson, T. “Of epistemic tools: Musical instruments as cognitive extensions”. Organised Sound 14.2: 168-176.. 2009.

- Olson, S. “ReCaptcha: Reusing your ‘wasted’ time online”. CNET. 2008.

- Di Scipio, A. “‘Sound is the interface’: from interactive to ecosystemic signal processing”. Organised Sound 8.3: 269-277.. 2003.

- Schnell, N. & Battier, M. “Introducing composed instruments, technical and musicological implications”. Proceedings of the 2002 conference on New interfaces for musical expression. 2002.

- Cagney, L. “CAGE Concert for Piano and Orchestra WOLFF Resistance”. Gramophone. 2021.

- Feldman, M. “Give My Regards to Eighth Street: Collected Writings, edited by BH Friedman”. Cambridge, MA, Exact Chang. 2000.

- Bourriaud, N. & et al.. “Relational aesthetics”. Dijon: Les presses du réel. 2002.

- Lewis, G. E. & et al.. “Interacting with latter-day musical automata”. Contemporary Music Review 18.3: 99-112.. 1999.

- Mogensen, R. “Evaluating an improvising computer implementation as a ‘partial creativity’ in a music performance system”. Journal of Creative Music Systems, 2(1):1–18. 2017.

- Einsenstein, S. “Film Form: Essays in Film Theory”. New York: Hartcourt; translated by Jay Leyda. 1949.

- Pudovkin, V. I. “Asynchronism as a principle of sound film”. Film sound: theory and practice: 86-91.. 1985.

- Cocteau, J. “Cocteau on the Film: A Conversation with André Fraigneau, trans”. Vera Traill. London: Dennis Dobson Ltd. 1985.

- Otey, C. “A Physical Model of the Piano for Sound Synthesis”. Submitted as coursework for Physics 210, Stanford University. 2007.

- Wessel, D. “Timbre space as a musical control structure”. Computer music journal: 45-52.. 1979.

- Huron, D. “Characterizing musical textures”. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library. 1989.

- Carpentier, T. & Barrett, N. & Gottfried, R. & Noisternig, M. “Holophonic sound in ircam’s concert hall: Technological and aesthetic practices”. Computer Music Journal 40, no. 4: 14-34.. 2016.

- Artaud, A. “Theatre and its Double”. Alma Books. 2018.