Unit 6: Networked Music Performance

Synopsis

This lesson will examine networked music from technical, performance and compositional perspectives, both historical and current. It will present historical precedents and early exemplar works and approaches, and provide some conceptual framing of telematic and networked performance. Computer networks, both remote and local, are defined and explained, as are the foundational technical software and hardware that facilitate networked performances over the Internet. A range of issues are explained, including how some of the ‘problems’ with networked music performance can be turned into creative concepts for new work. The impact and contributions of collaborative performance collectives is summarised, as are the realisation of networked music composition and performance in digitally native formats, such as laptop orchestras, augmented instruments, artificial intelligence and the networked music notation.

- Introduction

- Why make music over networks?

- Historical Precedents

- Early Exemplars

- Computer Networks

- What about the internet?

- What could possibly go wrong?

- Musicians on the network

- The contributions of collaborative networked music collectives.

- Laptop Orchestras

- From augmented instruments to AI

- Networked scores

- Conclusion

- References

“Networked music is no longer a future genre. The global quarantine event of 2020 launched the concept of performing together over the Internet into the mainstream” (Rebekah Wilson, 2020).

Introduction

The terms networked music performance (NMP) and telematic music performance (TMP) are often used interchangeably. However, there are important differences, because a network need not be telematic in nature. A network:

“occurs when a group of musicians, located at different physical locations, interact over a network to perform as if they would, if located in the same room” (Lazzaro et al., 2001)

Networked music performance has been called “the practice of conducting real-time music interaction over a computer network” (Gabrielli et al., 2016)

Telematic music performance, on the other hand, uses telecommunications and informational technologies to distribute sound and score information. It is a form of performance that involves “playing with words and sounds between people in distant locations using the Internet” (Alarcon, 2020). It is an approach that revolutionizes the traditional concept of musical interaction by enabling remote musicians to interact and perform together from remote locations through a telecommunication network (Rottondi et al., 2015) across geographic locations via the internet. Networked and telematic music performance sits within a larger range of art practice known as “communication art”. Frank Popper describes the six main characteristics of this genre in his important book, ‘Art of the Electronic Age’ (1993) where he states communication art:

- Stages physical presence at distance;

- Telescopes the immediate and the delayed;

- Focuses on the playfulness of interactivity;

- Combines memory and real time;

- Promotes planetary communication;

- and encourages a detailed study of human social groupings. (Popper, 1993)

Other related fields of communication art include telepresence, “a technology for a person to be present in some form in a distant place – the visual side of networking” (Wilson, 2020). Whilst the goal of the work is not necessarily to ‘communicate’, it is defined by the centrality of that function.

Why make music over networks?

In 1991, Pauline Oliveros famously asked ‘Why would anyone care to perform music between distance locations?” It’s a good question, and perhaps one we are still trying to answer. Oliveros notes that communication over long distance has been important to humans for a long time, for a range of purposes (Oliveros, 2009). As soon as telecommunications could occur, people were using them to make art. But it is worth noting that animals have been undertaking long range communications for much longer than humans. The record for acoustic long-distance communication is probably held by sperm whales (Clark et al., 2004). Their songs can carry hundreds of kilometres across the ocean using the acoustic properties of the sound fixing and ranging channels (or SOFAR channels; Ewing & Worzel, 1948). The communication distance is achieved via the whales’ use of low-frequency sounds, and varies according to local differences in the speed of sound underwater, due to changes of pressure and temperature (Oliveros et al., 2009).

American composer Maryanne Amacher is a largely overlooked thinker and practitioner of telematic listening. She undertook a range of long form sound experiments where she sent sounds fromone place to another over phone lines, as exemplified by the series of works entitled ‘In City” (1967). Her article ‘Long Distance Music’ written in the early 1970s is a poetic reflection on listening in shared time over long distances, where she articulates the value of transmitting and listening outside our local environment. What she calls ‘communicating outside our own structures’ is framed as an important existential challenge to our perception of our own local environment, noting that ‘having to extend our listening in this manner extends our receptivity to each other – to the music we are making in the very room we are in” (Amacher, 2020) p78).

The appeal of making music over networks includes the innovation in new ways of making, sharing and listening to music together, of making sense of new communication technologies and being part of the desire to be producers, as well as consumers, of meaning (Solnit, 2016) p 100. Networked music making is forum for reading music together, improvising together, performing in one and many places at the same time, and in effect helping us to understand the very nature of performance itself.

Apart from the obvious need to connect during the recent pandemic, awareness of the potential for networked connection over the internet has occurred before. The need to understand some basic concepts around networked collaboration peaked during the start of the file sharing era epitomised by Napster in the early 2000’s, and again in the early 2010’s, when engagement with the online virtual world ‘Second Life’ was at it’s peak. Second Life provided an environment accessed via the computer screen where users could create avatars and participate in a range of ‘life’ activities, including making music and art.

Rotating Brains Beating Heart (2010) is a collaborative virtual reality performance undertaken in the networked online platform ‘Second Life’ by Stelarc, Pauline Oliveros, Tina Pearson, Norman Lowrey, Andreas Müller and the Avatar Orchestra Metaverse.

Historical Precedents

The first network musical performance was probably held on 29th December 1874 when American electric engineer Elisha Gray tested his Musical Telegraph, also one of the first electric music synthesizers. Operated by a two-octave piano keyboard, the Musical Telegraph’s oscillators were steel reeds driven to vibration by electromagnets and transmitted for remote listening over a telegraph wire (Freeth, bower et al). It featured a keyboard transmitter, designed to “transmit tunes so produced through an electric circuit and reproducing them at the receiving end of the line” (Elisha Gray, Patent notes No. 173618 February 15, 1876). Thus music was sent via ‘telegraph’ over telephone wires, documented to at least 2400 miles.

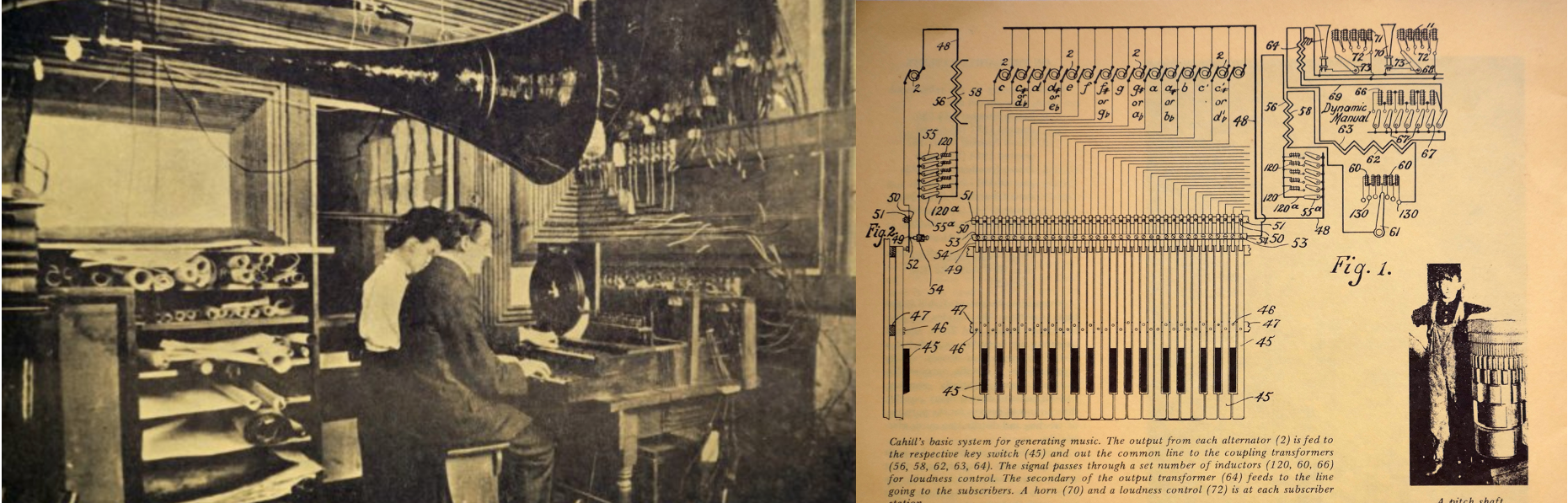

Another important early example of an instrument devised to send sound to other locations was American inventor Thaddeus Cahill’s ‘Telharmonium’, an early electric organ, which whilst developed in 1897, saw its first public performance in 1904 broadcasting live music across phone wires. Developed as an apparatus for generating and distributing music electrically, this instrument weighed some 210 tones, and could drive 15,000–20,000 telephone receivers. The actual mechanism of the instrument itself occupied an entire room in addition to the performers interface. Given that telephone technology was intended for transmitting voice communication only, the quality of sound in music reproduction was limited, meaning these bespoke instruments played a valuable role in accepting music transmission as possible. The conceptual frameworks for ‘communication art’ were soon in place, and evidenced in early examples such as László Moholy-Nagy’s “EM2 (Telephone Picture)” (1923), which used a telephone to transmit directions for the fabrication of paintings. However, the transmission instruments such as the Teleharmonium and Musical Telegraph were soon replaced by radio transmission, which provided a more efficient method for sending music to different locations. However, these instruments provided us with the first audio servers, with Cahill claiming his Teleharmonium allowed you to “Get Music on Tap Like Gas or Water” (1904).

The first radio broadcast dates back to 1910, with an experimental transmission of Mascagni’s ‘Cavalleria Rusticana’ and Leoncavallo’s ‘Pagliacci,’ featuring the Italian tenor Enrico Caruso, sent from the Metropolitan Opera House in New York city, USA. It is interesting to map the development of the radio from a large piece of wooden furniture with a speaker inside, to the handheld plastic portable transistor device with headphones connected, into the Internet streaming medium we see today, as it provides an important foundation for the development of distributed music. Radio also maps a trajectory from fixed to mobile reception. It was a starting point for the acceptance of the disembodied voice, and the instantaneous dislocation of music from it’s physical location of production to floating in the ‘ether’ of wireless communication (Hope, 2020) p47. A fundamental change to the way people engaged with listening, making and performing music occurs when a broadcasts from a singular location can be transmitted to any number of places or spaces anywhere in the world and beyond, paving the way for interactivity, mobility, networked music performances and listening.

Early Exemplars

Following on from telematic transmission of performance signals, was the networking of them – from a range of parallel signals to a system of interconnected ones. Early exemplars of this kind saw engagement with extant networks, such as radio and telephone phone communication, and later, using these as platforms to establish bespoke networks within and across them.

The first artwork claimed to engage with networking was a work entitled ‘Public Supply 1’, by Max Neuhaus in 1966. In this work, he combined a radio station with the telephone network and created a two-way public aural space across New York City, where any inhabitant could join a live dialogue with sound by making a phone call. This concept was developed further in 1977 with ‘Radio Net’, where he formed a nationwide network with 190 radio stations.

Phone art continues to evolve as technologies have, using the ‘telecommunications network’ as a true network as initiated in Neuhaus’s early experiments. ‘Art By Telephone’ even merited it’s own exhibition at the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art in 1969. A more recent example of phone art is ‘Dialtones: A Telesymphony’ (2001) by Golan Levin, one of first works to use mobile phones in a concert setting, engaging audience members’ mobile phones to contribute parts to a musical work. In this piece, a computer would “call” the phones so that a range of custom ringtones installed earlier could be heard, turning the mobile phones into musical instruments, and a music ensemble. A plethora of repertoire based mobile phone orchestras has since evolved, starting with American artists’ Ge Wang’s MoPho Orchestra, a mobile phone orchestra founded at Stanford University in 2007.

‘Sky Ear’ (2004) by British artist Usman Harque is a sound installation consisting of a floating, glowing cloud of LED embedded balloons that listens and reproduces electromagnetic waves in the sky. It replays electromagnetic fields (EMF) found in the atmosphere that have been created by phone calls, text messages, CB radio, television broadcasts, garage door openings, wireless laptops and other thousands of devices in a mix with naturally occurring EMF. ‘Sky Ear’ is a one-night event in which a glowing “cloud” of mobile phones and around 1000 extra-large helium balloons communicating with each other via infra-red are released into the air. People can dial into the cloud and listen to the sounds of the sky, but also send signals to create larger patterns across the entire ‘Sky Ear’ cloud. This is a work where the users of everyday consumer objects participate – not always willingly– in a sonic network of natural and human designed sounds

One of the earliest examples of an electronic interdependent network as the foundation for a piece of notated music can be found in American composer John Cage’s “Imaginary Landscape No. 4” (1951) for twelve radios (Pritchett, 1993). The piece used radio transistors as musical instruments, and performers operated them according to notation published by Peters Edition. The transistor radios were interconnected via the radio bands, which would change according to location. The work is also important because it is an early example of notation for electronic instruments (in this case radios).

Playing together by engaging with networks was something of a theme in other works by Cage. An example is Variations VII (1967), a text score (reporting an event after the fact) that suggests an electro acoustic system in which performers are allowed to act in a free and unscripted manner using only sounds that are created during the performance in realtime. In the original performance, movements of performers trigger sounds and people ‘phoned in’ to the performance. Both these works engage and create networks that provide ways for performers to relate to each other that would be impossible in a more conventional, instrumental performance.

Computer Networks

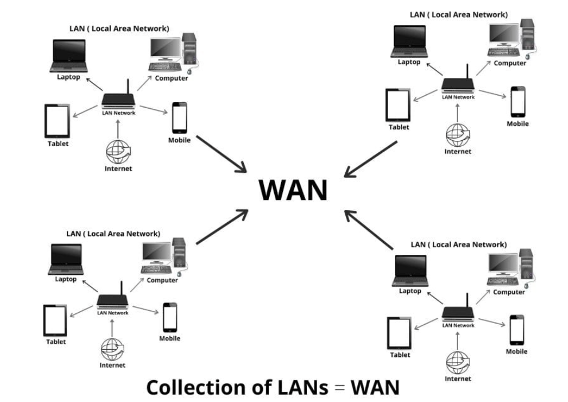

We have examined works that engage with existing networks as pathways (telecommunications), but also exerting their influence over the results of performances (radio). Computers expand upon these approaches by enabling bespoke network creations, between computers connected over a Local Area Network (LAN) or further afield across a Wide Area Network (WAN), the latter including the Internet

It is worth thinking about the rationale for creating music composition and performance across computer networks. Does it seek to emulate existing music processes using new tools, or engage these networks to create completely new ways of making music? Some of the more well-known technical limitations of networking computers over the Internet, for example, provide the opportunity to create music differently, rather than attempting to emulate extant ways of music production. In this context, it is useful to examine some of the technial paramaters of computer networks.

Computer networks can be built via a peer to peer connection (Oliveros et al., 2009)(Chafe) as epitomised by the aforementioned file sharing services, or a client to server design (Oliveros et al., 2009)(Braasch) as exemplified by web browsers. The networks themselves use a range of technologies to create connections such as (but not limited to) wired connections, Bluetooth, proprietary solutions (embedded in items such as wireless headphones, speakers or even cinemas), stage microphone wireless audio transmitters (VHF and UHF), controllers, effects processors, body sensing and transmission hardware, wireless transmission of control signals (sending MIDI signals to hardware) and home WiFi. Signals can be sent from computers but also a range of other mobile devices and embedded platforms.

What about the internet?

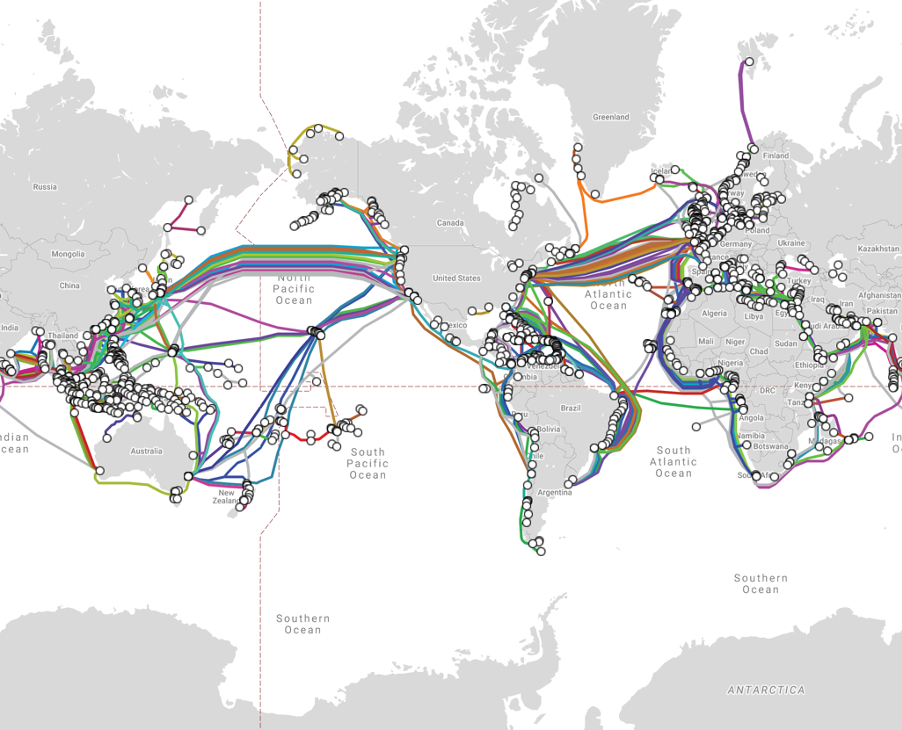

Performing telematic, networked performance over the Internet is one of the most recent ways of building and sharing music created via computer networks. There are some key considerations worth examining that outline both the challenges and opportunities afforded by this technology. Firstly, it is worth remembering that communications of any kind across time and space are limited by physics, in particular the speed of light and sound through any substance. The Internet today is currently shared across the word via undersea cable, that is not always laid in the most direct route, resulting in some larger than expected distances for data to travel.

The Internet enabled computers to communicate with each other for the first time. Whilst the Internet was invented in 1983, the development of high-speed internet over provisioned and dedicated cable backbones was introduced in the early 2000s, and began operations under a consortium led by the USA and known as Internet2. This network links a mix of educational, research and business groups such as the GEANT network in Europe, TIEN in Asia and AARNET in Australia with high quality optic fibre cable. Internet2 made high quality audio links possible beginning in the early 2000s, seeing an uptick in creative networked music performance since then.

Internet Protocols and Audio transfer

A protocol is the conceptual model used in the internet and computer networks. The foundational protocol for Internet networking is the combined Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the Internet Protocol (IP), known as TCP/IP. The development of this networking method was funded by the USA Defence Department, the founders of the Internet, through the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and in 1982, the Department declared TCP/IP as the standard for all military computer networking (Oliveros et al., 2009). A more recent example of a networking protocol is Open Sound Control (OSC), a content format for musical purposes that prescribes a message formatting useful for description, content and timing information exchange between software synthesizers, mixing consoles, etc (Wright, 2005).

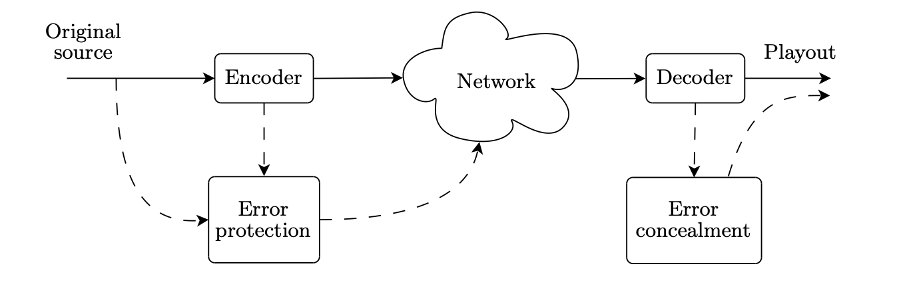

Audio is stored as digital samples, grouped into packets. These packets are sent over the network, then converted back into analogue signals for listening via speakers or headphones. This uses digital to analogue (D/A) and analogue to digital (A/D) converters. TCP/IP is suite of information that provides end to end data communication, specifying how data should be packetized, addressed, transmitted, routed, and received. Digital audio streams also need to be encoded into one of a range of different formats, such as FLAC, Mp3 or any one of many others. Below is a diagram that provides an illustration of how the delivery of data are delivered and received via the Internet, and how things can go wrong if packs are missed or received in the wrong order, explain the need for error correction.

Bandwidth for data transfer

High definition audio streaming is required to enable sounds to reflect their design at origin as much as possible, and this requires a high level of bandwidth. Bandwidth is the amount of data that can be transferred from one point to another within a network in a specific amount of time, often expressed as a pipe line. Bandwidth is expressed as a bitrate, initially measured in bits per second (bps) but more recently as giga or terabits per second. For audio information to be sent over networks, a rate of transfer has to be considered. In addition, a buffer is often provided to allow a constant stream of sound as each packet arrives from the sender. Bandwidth is generally wider in wired connections, however, wireless protocols are improving all the time.

Needing generous bandwidth is one way of recognising that music a very time sensitive form of communication (Carôt et al., 2007) p.1. Since data is exchanged in packets, and computing architectures are more efficient with chunks of data rather than on a sample-by-sample basis, the only current feasible way to experience audio data as a continuous flow is to store and exchange buffered data. The buffer size and the sampling rate determine a blocking time or buffer time.

Realtime Transfer Protocols

The Realtime Transfer Protocol (RTP) is a network protocol designed for the delivery of audio and video over networks operating over IP. RTP typically runs over User Datagram Protocol (UDP), and is used in conjunction with the RTP Control Protocol (RTCP). While RTP carries the media streams ( audio and video), RTCP is used to monitor transmission statistics and quality of service (QoS). It is particularly useful for the synchronization of multiple streams.

What could possibly go wrong?

There are three broad technical areas where things could go wrong in wireless networked music performance – audio delay (latency, network delay), audio dropout and synchronisation. (Gabrielli et al., 2016) outline these in detail in their book ‘Wireless Networked Music Performance’, and I have summarised them here. As alluded to earlier, these ‘issues’ can be the spring board to new creative ideas around music, that may not arise otherwise.

Audio Delay

Audio delay (latency) refers to how much time it takes for a signal to travel to its destination and back, and is one of the most commonly reported, and discussed, frustrations with networked music performance and listening. Many musicians do not realise that they are used to certain levels of latency already, due to the speed of sound in different acoustic locations. However, latency over digital networks adds additional time lags that results from two key issues - the finite speed of light over long distances of Internet cable, and the delay of audio in a buffer at the receiving end.

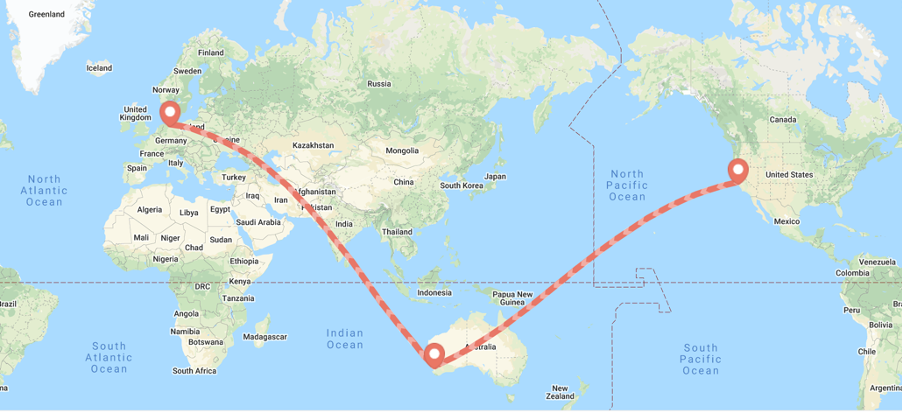

The speed of sound creates latency, even before transmission over the Internet. Roger Dannenberg provides a great comparative example to explain the physics of data travelling in space and time that I will summarise here (Dannenberg, 2020). A violinist and cellist on the outer sides of a string quartet performing in a concert hall could experience 16 milliseconds of latency due to the speed of sound, something they would be accustomed to and take for granted from a psycho-acoustic perception perspective. The speed of the Internet, over fibre optic cable, is subject to the latency induced by the speed of light. A round trip from the US cities of Pittsburgh to San Francisco is around 8220 kilometres, and this would create around 78 milliseconds of latency, considerably more than that experienced in the concert hall example when added to it. Fibre optic cables carry data faster and cheaper than satellites.

Unsurprisingly, musicians find it remarkably challenging when they hear other members of their ensemble ‘out of time’ with their own instrument, as playing ‘in time’ is a key ingredient for many genres of music. Below is a diagram of the point to point distances involved in a performance between Germany, Australia and the USA. However, the Internet cables are not necessarily point to point, as illustrated above. And this is with improvements that come with the introduction of, Internet2, such as manually routing of signals, reducing the number of switches in the path.

In addition to latency induced via the Internet, also known as ‘transmission delay’, latency can also be introduced from each local system when audio is processed, as well as variability of the speed of the computer’s connection to the network (e.g. a via a router) before it even gets to the Internet transmission point. This has led Braasch to outline two types of transmission latency –propagation and system (Oliveros, 2009) (p.423). Propagation latency is caused by transmission limits causing delays, and system latency is usually attributed to signal processing speeds of the telematic apparatus, but also the local machines and networks. The computer’s processing speed of converting sound to data and vice versa is another contributor, as sound cards process data in blocks that can lead to a delayed audio stream.

This range of factors all make part of a broader concept of network delay, and can be subject to wide range of further variations. Bandwidth variations can create what is known as ‘network jitter’. This depends on the ping rate, which is a measure of the response time it takes for a message to go from your computer to a server and back. If the network delay is not constant, transmission can vary from packet to packet, and create jitter. Delay jitter is caused by the receiver storing and reordering packets, then waiting for late ones before sending them on to playback. This jitter cannot be avoided in most wireless Internet exchanges, but it can be mitigated or compensated for, by estimating what may happen, and allocating sufficient buffering to allow late packet arrival.

‘Ping’ (2001) is a work developed by software developer and musician Chris Chafe. It is a sonic adaptation of a network tool commonly used for timing data transmission over the Internet. The work sonifies network connections according to the temporal delays involved in sending messages between two nodes, making audible the delay that exists when networked computer data is transferred between different sites.

Listen to and iteration of ‘Ping’ (2001) by Chris Chafe. You can also read about this set up for this piece here.

Other problems

Most networked music performance issues are due to the delay, drop or synchronisation of data being sent over the network. In addition to the types of audio delay (latency) discussed above, audio dropout, algorithmic delay and synchronisation can create interruptions, and even complete collapse of the audio stream. Audio dropout can be caused by loss of packets along the route, the late arrival of packets at the receiving end, a loss of transmitter and receiver audio clock synchronization or a failure in the scheduling. Given that a regular audio flow is a key element of any music performance, it is important to avoid these when musical communication is required.

Audio blocking delay is caused by audio buffering occurring before or after the A/D and D/A conversion. The converters for this purpose are explicitly designed to convert audio in real time, but the issue can arise when data storage and buffering are inconsistent. Further, the slowing down of audio compression processes can create what is known as algorithmic delay. Once signals are discretized and quantized, they need to be transmitted. When bandwidth is inconsistent or too narrow, the encoding and compression of audio is employed, and this can effect both audio quality and create a latency created by the computing, or algorithmic work, required.

Also, computers feature hardware clocks, to ensure accurate timing functions. These can drift with respect to each other and create synchronisations problems for audio with other media such as video. This is important when the vision, as well as the audio, of the performance are being transmitted together, and can result in sound being ‘dislocated’ from the video. This was first discovered in a range of proprietary video conferencing solutions, that introduced an artificial delay to the audio to compensate for any irregularities with the synchronisation of audio with the video system.

Musicians on the network

You may be wondering, how much latency is too much, if you want to replicate in person performance, and engage in more traditional types of musical interaction. Studies have shown an acceptable level of latency for music performers to feel and sound ‘natural’ is below 30 milliseconds (Kurtisi et al., 2006), as illustrated in the Dannenberg example of 25 milliseconds. This is considered to be the bounds of human perception as experienced in an averaged sized room (Rottondi et al., 2015). It is worth remembering that this depends a lot on the style of music being played – a free jazz improvisation would have different expectations around time alignment than a Bach Cantata. Generally, a stable latency of 25 milliseconds between two rhythm-based instruments (such as drums and bass) is through to be optimal (Carôt, 2007), and a broader guide for the threshold of effective musical communication is 25–50 milliseconds (Sawchuk et al., 2003).

Various types of software can be employed to mitigate the perception of delay, or at the least, control this perception. Jacktrip, developed by a team lead by Chris Chafe at CCRMA at Stanford University, USA, is one example of software than can be employed to provid low-latency, bidirectional, uncompressed audio streaming for networked performance. It was used in this telematic rendition of American composer Terry Riley’s ‘In C’ (1964). ‘In C’ is a scored work for an infinite number of performers’, presented as a series of fifty three short, melodic fragments lasting from half a beat to 32 beats. Each phrase may be repeated an arbitrary number of times at the discretion of each musician, s leaving some ‘space’ or flexibility around timing between musicians, making it an interesting and realisable notated work for a telematic performance.

Whilst much research and development focus is on removing latency and improving audio quality in networked music performance, some performers and composers have adopted these characterises as welcome elements. Carot and Werners ‘Latency Accepting Approach’ (2007) is an example of a model of high latency performance where delays beyond twenty five milliseconds are not only accepted, but also consciously and systematically taken into account. Networked music performance provides an opportunity to find entirely new ways of making music, rather than as a system to emulate offline experiences. Swedish composer Anders Lind directly references this “Latency Accepting Approach:” when he creates what he calls ‘Latency Music’ facilitated by a combination of MaxMSP and AudioMovers software to control, but not eradicate, latency.

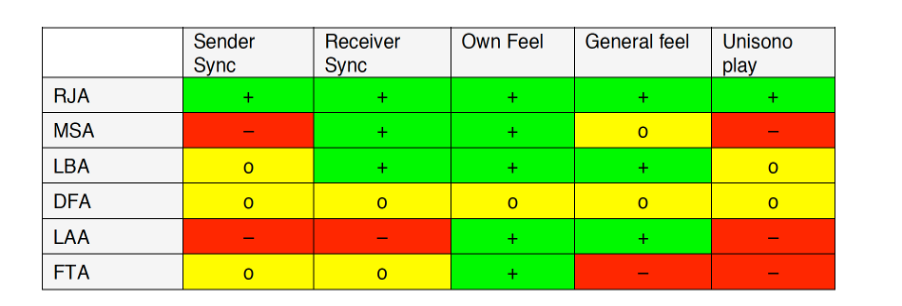

The Latency Accepting Approach (LAA) is one of four approaches suggested by Carot and Werner when dealing musician relationships within telematic performance. The others are Realistic Interaction Approach (RIA), Master Slave Approach (MSA), Laid Back Approach (LBA), Delayed Feedback Approach (DFA) and the Fake Time Approach (FTA). These are affected by five factors across synchronisation and musical ‘feel’. These include ‘sender sync’ and ‘receiver sync,’ that describe the rhythmical synchronisation of the players’ signals in a musical interaction. ‘Own feel’ is an indicator for how realistic playing the own instrument feels for each player. ’General feel’ reflects how realistic the session feels in comparison to a conventional music session in the same room, and ‘mnisono play’ shows if musicians will be able to play the same notes at the same time. How well an aspect is fulfilled by each category is indicated by ‘+’ (good), ‘o’ (average) or ‘–‘ (bad) (Carôt et al., 2007).

They prepared a table outlining the experience of these interactions from a musician’s perspective:

‘The Apart Study’ (2007) is a collaborative music ensemble project where artificial latencies of up to 125 milliseconds are introduced between three studio locations, while asking musicians to perform both metrically determined music and free improvisation guided by avatars. Developed at the Sonic Arts Research Centre, the work is an exploration of issues of synchronicity and music ensemble communication in the context of network performance (Schroeder et al., 2007).

The contributions of collaborative networked music collectives.

Groups of musicians brought together through a common interest in new ways of playing and composing music with computers existed well before the introduction of the Internet to common public use. Assembled as collectives of musicians, composers and programmers, these groups were key in the ongoing evolution of networked music performance, as an essentially collaborative practice.

Facilitated by the emergence of cheap personal computers in the 1970s, groups like the League of Automatic Music Composers (LAMC) began to experiment with linking multiple computers, electronic instruments, and analogue circuitry to create novel forms of music (Bischoff et al., n.d.) . This improvisational group was operational between 1978 – 83 and undertook some of the first collective computer networking experiments in music. They engaged the first personal computer on the market, the Commodore KIM 1, as a live musical instrument. By networking of several regulated computers, they enabled unlimited interactions between players and signals.. The group often engaged biological and social systems as structural and guiding models for performances and compositions (Bischoff et al., n.d.).

Out of the ‘Network Muse’ network music festival in California in 1985, the performance collective ‘The Hub‘ was established. This group made early experiments sending MIDI data over ethernet cable to various distributed locations, as well as performances featuring spectral analysis of acoustic objects, room resonance as a data source, and hyper-improvisational mapping of shared values (Sawchuk et al., 2003). Member Mark Trayle, explains how:

“our work is characterized by the sharing of digital information via a network, which is used to algorithmically influence the music played by each player in the group. This form of interaction provides the opportunity for composer/performers using computers to use the unique attributes of this instantaneous sharing to create new ensemble relations. The musical behavior that results when each performer individually creates their own realization of a data-sharing specification in a variety of computer music languages affords a rich and unpredictable environment. Emergent behaviors and inexplicable synchronicities abound, and are used to enhance a collaborative, and improvisational performance practice“(Gresham-Lancaster, 1998) (p.40).

With the advent of MIDI and software sequencers in 1990, members Gresham-Lancaster and Perkis designed a MIDI-based Hub, where each musician’s machine was assigned a MIDI port and MIDI messages were employed to exchange data. In 1998, the group undertook an early three-way audio only performance across Poland, Finland and Sweden entitled ‘Mélange à trois’(Sawchuk et al., 2003).

SensorBand was a European based trio of musicians active between 1993-2003 using interactive technology such as gestural interfaces that engaged ultrasound, infrared, and bioelectric sensors as musical instruments. Their projects centered around the theme of physicality and human control in relation to technology, and much of their work was inspired by augmented instruments. ‘Global String’ (2002) is a networked music installation, where multiple sites are connected via the Internet.

One of the first research groups to take advantage of the improved network performance of Internet2, was the SoundWIRE group at Stanford University’s CCRMA. The centre is sill active in it’s development of the JackTrip software amonngs other developments includingthe Distributed Immersive Performance experiments (Sawchuk et al., 2003), SoundJack, and DIAMOUSES. Many members took part in a well documented 2007 networked telematic performance between Stanford, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, and University of California San Diego using JackTrip and video software was iCHATav (Oliveros et al., 2009).

The European Bridges Ensemble was established in 2005 for Internet and network performance where the development and performance of works created involved no physical contact between the composers whatsoever. Featuring members across central European cities, they often performed with Georg Hajdu’s interactive network performance environment Quintet.net, a collaborative network software in MaxMSP that is still being developed today (Hajdu et al., 2009).

Laptop Orchestras

Laptop orchestras provide a wide range of possibilities for natively digital music to be networked. Perhaps the most well known is the Princeton Laptop Orchestra, PLOrk, which began in 2006 by taking the traditional model of the orchestra and reinventing it with musicians they call ‘laptopists’ (Trueman et al., 2006). In PLOrk, each laptopist performs with a laptop and custom designed hemispherical speaker that emulates the way traditional orchestral instruments cast their sound into space. Wireless networking and video augment the familiar role of the conductor, proposing new ways of organizing large ensembles. The group uses a LAN to synchronize devices that are running Max and ChucK software applications to synthesize and process sound (Trueman et al., 2006) (p.12).

A laptop orchestra focused on telematic networked performance is the Female Laptop Orchestra (FLO), founded in 2014 by Nela Brown. The project is a telematic, multi channel audio visual performance collaboration connecting female musicians, sound artists, composers, engineers and computer scientists globally through co-located and distributed collaborative music creation (Female Laptop Orchestra, n.d.). Each FLO performance is site-specific and performer-dependant, mixing location-based field recordings, live coding, acoustic instruments, voice, sound synthesis and real-time sound processing using Web Audio API’s and VR environments with audio streams arriving from different global locations (Female Laptop Orchestra, n.d.).

From augmented instruments to AI

Early experiences in networked performance have led to a range of augmented instruments and robotic composers and performances that communicate over wireless networks, that continue to evolve and develop. Some of the earliest ‘established’ acoustic instruments to be augmented by networked facility include pianos.

In 1992, a piano collaboration between Jean Claude Risset and Terry Riley in France, as well as David Rosenboom and Morton Subotnick un the USA, was facilitated by the Yamaha Disklavier, a full size piano fitted out with MIDI controls to the capture of locally and remotely produced pianists playing. Entitled ’Transatlantic Concert’, the telematic connection was made using satellite links, rather than cable Internet. Similar projects have followed with these Disklavier’s, including George Lewis’s ‘Spooky Interaction’ (2014), a composition for two human pianists and two computer-driven virtual improvisors implemented in Max/MSP by Damon Holzborn. The work was performed across New York USA and Melbourne, Australia using early versions of the teleconferencing system Polycom, with the intention to synchronise video and audio seamlessly.

Gil Weinberg is an artist who is interested in the way real-time collaborations between human and robotic players can capitalize on the combination of their unique strengths to produce new and compelling music. Communication protocols are at this heart of his work, which aims to capitalise on the combination of human qualities such musical expression and emotions, with robotic traits such as powerful processing, the ability to perform sophisticated mathematical transformations, robust long-term memory, and the capacity to play accurately without practice (Weinberg et al., 2002).

An early project of his is ‘Beatbugs’, a series of hand-held percussive instruments that allow the creation, manipulation, and sharing of rhythmic motifs through a simple interface. When multiple Beatbugs are connected in a network, players can form large-scale collaborative compositions by interdependently sharing and developing each other’s motifs. Each BeatBug player can enter a motif that is then sent to other players in the network. Receiving players can decide whether to develop the motif further (by continuously manipulating pitch, timbre, and rhythmic elements using two bend sensor antennae) or to keep it in their personal instrument (by entering and sending their own new motifs to the group). The tension between the system’s stochastic routing scheme and the players’ improvised real-time decisions leads to an interdependent, dynamic, and constantly evolving musical experience. (Weinberg et al., 2002). His more recent work with robotics and AI push up against the limits of ‘musicianship’ by having robots collaborate with humans, and each other.

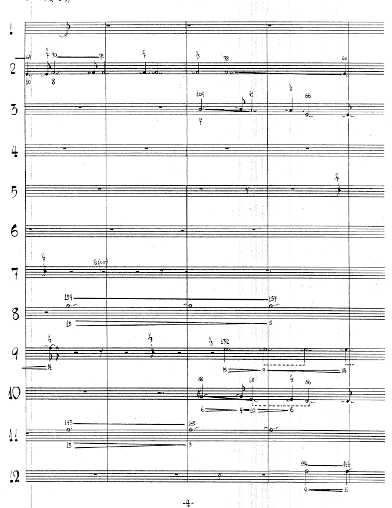

Networked scores

In addition to performance and composition over the Internet, scores can distributed via networks. A range of software model have been developed so that musicians may read various types of music notation simultaneously over the Internet, and from remote locations, further enhancing the possibilities of networked performance. Further, computing has seen a plethora of generative notation systems, creating a range of ‘extreme sight reading’ scenarios (Freeman, 2008) where musicians attempt to read notation generated by computers in realtime. Jason Freeman’s, ‘Glimmer’(2004) for chamber orchestra and audience participation features computer-controlled LED lights that display the real-time notation to each musician (Freeman, 2008) (p.32). Each audience member is given a light stick which they wave throughout the piece, and computer software analyses and sends as instructions to each musician.

Lindsay Vickery is an Australian composer who has been working on various kinds of scores distributed over networked laptop computers. Devising score generation methods in MaxMSP software, Vickery also creates real time electronic effects on live acoustic instruments in the same sofrware. His scores often engage bespoke interfaces for the performers to read, including non linear models, in works such as ‘Transit of Venus’ (2009) where performers read a range of symbols in motion.

Recent developments in music notation include a range of dynamic and interactive formats that have grown from computing, including 3D animation, that can be read from different perspectives in different locations, creating additional perspectives to the concept of ‘distributed notation’ (Rebelo, 2010). He is also one of the developers of the Decibel ScorePlayer, and iPad application for networking predominately graphic notation, which can also feature audio embedded in the digital file read by the application (Hope et al., 2015). Decibel is an Australian new music ensemble (of which this author is a member) that operates something like the music collectives outlined above, with a membership of composers, performance, sound engineers and software programmers. The Decibel ScorePlayer software has evolved from within the ensemble, first as a bespoke MaxMSP program to a more recent iteration in the Apple App store.

Conclusion

Networked music performance is in a growth phase. Early experiments have shaped software and instrument design, as well as the trajectory for a range of wireless applications and artificial intelligence. As we move beyond computer screens and into more three-dimensional computer renditions, both visual and audio, the ongoing exploration of possibilities for networked music performance, composition and notation will only become more relevant and diffuse.

References

- Alarcon, X. “Telematic Sonic Performance introduction”. The Sampler. Accessed 20.05.2021. 2020.

- Amacher, M. “Selected Writings and Interviews”. Bill Dietz and Amy Cimini. New York: Blank Forms. 2020.

- Barbosa, A. “Displaced soundscapes: A survey of network systems for music and sonic art creation”. Leonardo Music Journal, vol. 13, pp. 53–59. 2003.

- Bischoff, J. & Brown, C. “INDIGENOUS TO THE NET: Early Network Music Bands in the San Francisco Bay Area”. Crossfade. Retrieved 20.09.2021. n.d..

- Carôt, A. “Traffic Engineering and Network Music Performances”. Technical Report at University of Luebeck, Germany. 2007.

- Carôt, A. & Werner, C. “Network music performance-problems, approaches and perspectives”. In Proceedings of the “Music in the Global Village”-Conference, Budapest, Hungary. Vol. 162, pp. 23-30. 2007.

- Carôt, A. & Krämer, U. & Schuller, G. “Network Music Performance (NMP) in Narrow Band Networks”. In 120th AES convention, Paris, France, 20-23 May. 2006.

- Clark, C. W. & Clapham, P. J. “Acoustic monitoring on a humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) feeding ground shows continual singing into late spring”. In Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 271(1543), pp. 1051-1057.. 2004.

- Cook, M. “Telematic Music: History and Development of the Medium and Current Technologies Related to Performance”. Doctor of Musical Arts Dissertations.. 2015.

- Dannenberg, R. “Music Performance over Networks and the Latency Problem”. Accessed 30.08.2021. 2020.

- Duckworth, W. “Making music on the web”. Leonardo Music Journal, vol. 9, pp. 13–17. 1999.

- Female Laptop Orchestra, FLO. “”. Accessed 20.09.2021. n.d..

- Freeman, J. “Extreme sight-reading, mediated expression, and audience participation: Real-time music notation in live performance”. Computer Music Journal, 32(3), pp 25-41. 2008.

- Gresham-Lancaster, S. “The Aesthetics and History of the Hub: The Effects of Changing Technology on Network Computer Music”. Leonardo Music Journal, 8, 39–44. 1998.

- Gabrielli, L. & Squartini, S. “Wireless networked music performance”. In Wireless Networked Music Performance. Springer, Singapore. pp. 53-92. 2016.

- Kurtisi, Z. & Gu, X. & Wolf, L. “Enabling network-centric music performance in wide-area networks”. Communications of the ACM. 49 (11). pp. 52–54. 2006.

- Freeth, B. & Bowers, J. & Hogg, B. “Musical Meshworks: from Networked Performance to Cultures of Exchange”. In Proceedings of the 2014 conference on Designing Interactive Systems (DIS 14). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, pp. 219–228.. 2014.

- Hajdu, G. & Didkovsky, N. “On the Evolution of Music Notation in Network Music Environments”. Contemporary Music Review, 28:4-5, pp. 395-407. 2009.

- Hauben, R. “From the ARPANET to the Internet”. TCP Digest (UUCP). Retrieved 5.7.2021. 2007.

- Hope, C. “From Early Soundings to Locative Listening in Mobile Media Art”. In The Routledge Companion to Mobile Media Art. Routledge. pp. 46-56.. 2020.

- Hope, C. & Wyatt, A. & Vickery, L. “The Decibel ScorePlayer: New developments and improved functionality”. In Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference. CEMI, University of North Texas. 2015.

- Hope, C. “From Early Soundings to Locative Listening in Mobile Media Art”. In The Routledge Companion to Mobile Media Art. Routledge. pp. 46-56. 2020.

- Lazzaro, J. & Wawrzynek, J. “A case for network musical performance”. NOSSDAV 01: Proceedings of the 11th international workshop on Network and operating systems support for digital audio and video. ACM Press New York, NY, USA. pp. 157–166.. 2001.

- Lemmon, E. C. “Telematic Music vs. Networked Music: Distinguishing”. Between CybernJournal of Network Music and Arts 1, pp. 1. 2019.

- Mills, R. “Tele-Improvisation: Intercultural Interaction in the Online Global Music Jam Session”. New York: Springer. 2019.

- Oliveros, P. “Networked Music: Low and High Tech”. Contemporary Music Review, 28:4-5, pp. 433-435, DOI: 10.1080/07494460903422412. 2009.

- Oliveros, P. & Weaver, S. & Dresser, M. & Pitcher, J. & Braasch, J. & Chafe, C. “Telematic Music: Six Perspectives”. Leonardo Music Journal, 19, 95–96.. 2009.

- Open Sound Control, OSC. “Open Sound Control”. Accessed 21.09.2021. n.d..

- Popper, F. “Art of the Electronic Age”. NY: Harry N. Abrams. 1993.

- Pritchett, J. “The Music of John Cage”. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 1993.

- Rebelo, P. “Notating the Unpredictable”. Contemporary Music Review 29, no. 1, pp. 17 – 27. 2010.

- Rofe, M. & Geelhoed, E. & Hodsdon, L. “Experiencing Online Orchestra: Communities, connections and music-making through telematic performance”. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 10:2&3, pp. 257–275. 2017.

- Rottondi, C. E. M. & Buccoli, M. & Zanoni, M. & Garao, D. G. & Verticale, G. & Sarti, A. “Feature-based analysis of the effects of packet delay on networked musical interactions”. . 2015.

- Sawchuk, A. & Chew, E. & Zimmermann, R. & Papadopoulos, C. & Kyriakakis, C. “From remote media immersion to Distributed Immersive Performance”. In ETP 03: Proceedings of the 2003 ACM SIGMM workshop on Experiential telepresence. ACM Press New York, NY, USA. pp. 110–120.. 2003.

- Solnit, R. “Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities”. Third Edition. Haymarket Books. 2016.

- Schroeder, F. & Renaud, A. & Rebelo, P. & Gualda, F. “Addressing the Network: Performative Strategies for Playing Apart”. International Computer Music Conference. 2007.

- Tanaka, A. “Composing as a function of Infrastructure”. In Surface Tension: Problematics of Site. Errant Bodies Press: Los Angeles. 2003.

- Gray, E. “The ‘Musical Telegraph’ or ‘Electro-Harmonic Telegraph’”. 120years.net Accessed 20.05.2021. 1874.

- Trueman, D. & Cook, P. R. & Smallwood, S. & Wang, G. “PLOrk: the Princeton laptop orchestra, year1”. In the Proceedings of 2006 International Computer Music Conference. Accessed 20.06.2021. 2006.

- Weinberg, G. & Aimi, R. & Jennings, K. “The BeatBug Network: a rhythmic system for interdependent group collaboration”. In Proceedings of the 2002 conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression. pp. 1-6. 2002.

- Whalley, I. “Developing telematic electroacoustic music: Complex networks, machine intelligence and affective data stream sonification”. Organised Sound, 20(1), pp. 90-98.. 2015.

- Wilson, R. “Aesthetic and technical strategies for networked music performance”. AI & Society. Accessed 4.06.2021. 2020.

- Wright, M. “Open Sound Control: an enabling technology for musical networking”. Organised Sound, 10: 3, pp. 193- 200. 2005.