Unit 8: 'Technology as Practice' within Musical, Multimedia and Performance Arts: Responses and revivifications of Ursula M. Franklin's Massey Lectures from 1989.

Synopsis

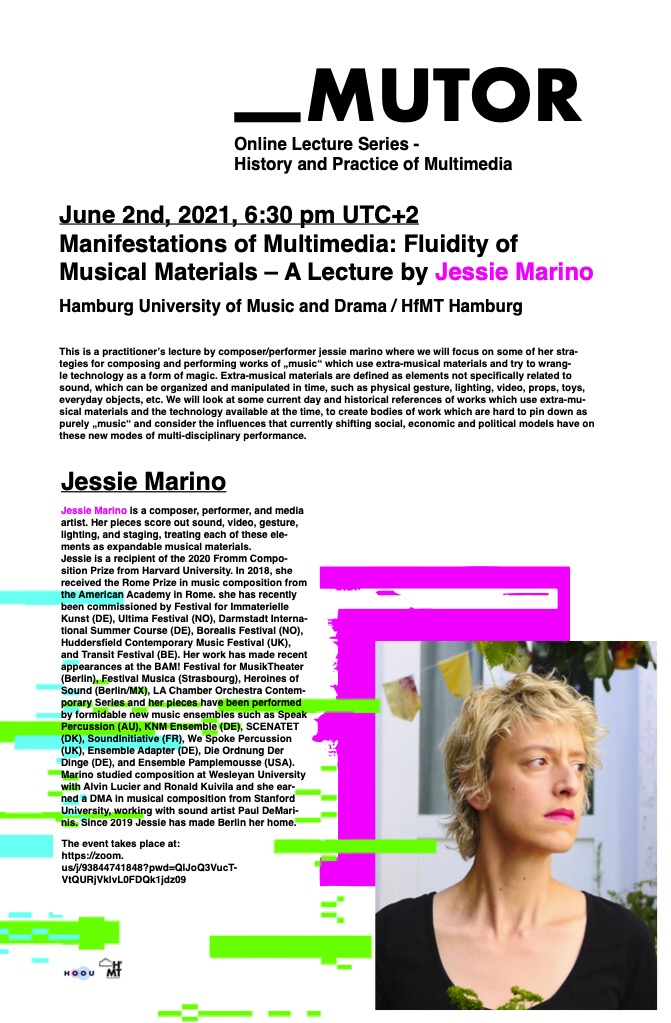

This is a practitioner’s lecture by composer/performer jessie marino where we will focus on some of her strategies for composing and performing works of ‘music’ which use extra-musical materials and try to wrangle technology as a form of magic. Extra-musical materials are defined as elements not specifically related to sound, which can be organized and manipulated in time, such as physical gesture, lighting, video, props, toys, everyday objects, etc. We will look at some current day and historical references of works which use extra-musical materials and the technology available at the time, to create bodies of work which are hard to pin down as purely ‘music’ and consider the influences that currently shifting social, economic and political models have on these new modes of multi-disciplinary performance.

Introduction

My name is jessie marino, I am a composer, a performer and a multimedia artist from Long Island New York - since 2019 I have lived and worked as a freelance musician in Berlin Germany. I consider myself a practitioner of sound, multi-media, and performance arts and also a habitual of collector of technology, not in a fetishized “got to catch em all” kind of way - but rather as a kind of creative resuscitator of technologically “infirm” devices.

When I lived in Palo Alto CA, I made weekly trips to the local second-hand near my home, hunting for audio/visual devices which were left at the curbside. These devices were considered by the Silicon Valley Slingers to be defunct or dead, not because they wouldn’t turn on, or show any other indications of quote, unquote “life”, but because they were outdated models which had been supplanted by “better” “newer” “more efficient” sibling-devices.

Because this series of lectures and classes are organized as an extension of HMFT-Hamburgs MUTOR lectures which addressed a broad range of topics in relation to Music Technology, today I want to discuss some thoughts about creative uses and definitions of technology, pseudo-realistic implementations of this technology in our current cultural landscape and give examples of how some of my favorite musical, multimedia and performance artists have used the tools of these technologies differently.

In preparing for this class, I found a wonderful set of five lectures given by Ursula M. Franklin as a part of the Massey Lecture Series in Toronto CA in 19891. Ursula Franklin was an experimental physicist, a Quaker, a feminist, a Holocaust survivor, a professor at the University of Toronto, a human rights and anti-war activist, and a wonderful writer and thinker on how technology has effected the political, social and cultural sectors. I will keep coming back to Ms. Franklins words in my own lecture and will use audio clips as revivifications of Ms. Franklin’s voice from her 1989 lectures titled “The Real World of Technology”. These lectures from over 30 years ago, I feel, are still prescient to our time, and I find it important since we indeed have the technological capacity to hear these words from their originator, that I’d like to indulge in the opportunity to provide you, the listener, with an additional sense of Ms. Franklin’s identity and politics through an auditory medium.

Technology as practice

Let’s begin with a definition of what technology is and what technology is not: Here, Ursula Franklin sets us up in the first of her Massey Lectures:

“I would like at this point to say what technology for me in this context is not. Technology is not the sum of the artifacts- of wheels and gears, of rails and electronic transmitters. For me, technology is a system. It entails far more than the individual material components. Technology involves organization, procedure, symbols, new words, equations, and most of all, it involves a mindset.” (Franklin, 1989)

In this definition, I find a simultaneous description of a conceptual art process. The artist brings together thoughts and people, implements their ideas through experiments and formulations of process, develops ways of communicating these ideas to each other and to a public forum, and through the act of performance or display, focuses on a mode of thinking about the world by creating a lens through which an audience may look.

I want to be clear that I don’t want to only define technology, as Franklin has here, as a practice. In art I think it is also useful to examine the wheels, gears and electronic transmitters - not necessarily by examining how they function or were calculated, but by what that technology enables the artist-practitioner to do, the political frames of how it was produced, and how the technology enables an audience to experience the work as a whole, and reflect upon their own interpretation of the world that surrounds them.

“Looking at technology, as practice, as formalized practice, has some quite interesting consequences. “Around here, that’s how we do things”, a group might say - and that’s their way of self identification. Because others”do the same thing differently”. A different way of doing something, a different tool for the same task, separates the outsider from the insider.” (Franklin, 1989)

“Kenneth Boulding, the author of “The Image”, and many other influential books in the social sciences, suggested that one might think of technology as ways of doing something…” (Franklin, 1989)

The choreographer Jonathan Burrows in his book “A Choreographers Handbook” says it in another way:

“Technique is whatever you need to do, in order to do what you need to do” (Burrows, 2010)(p. 68)

So what are we doing?- or rather - maybe it’s not only about what we do, but also about how we do it. Franklin makes a distinction between a holistic model of technological development and a prescriptive model. At the outcome, something is made - but how they are made has great impacts on the mindset of those who craft something and those who produce something.

“I would now like to introduce a concept that may be somewhat more difficult to grasp. I want to distinguish between two very different forms of technological development. The distinction that I need to make is between holistic technologies and prescriptive technologies. Again, we are considering technology as practice. But now we are looking (at) what is actually going on, what happens on the level of work in these two categories of holistic and prescriptive technologies have very different specializations and divisions of labor, and consequently they have very different social and political implications. Again, let me say, What interests me is not what is being done, but how it is being done. Holistic technologies are normally associated with the notion of craft. Artisans, be the potters, weavers, metalsmith, control the process of their own work from beginning to finish. And their hands and minds make situational decisions as the work proceeds. Be it on the wall thickness of a pot, on the shape of a knife edge, decisions that they only can make while are they working- and they draw on their own experience, each time applying it to a unique situation.

The products of their work are one of a kind. However similar the pots may look to a casual observer, each piece was made as if it were unique.” (Franklin, 1989)

“It is quite different from the specialization by process, which I call prescriptive technology based on a quite different division of labor. Here, the making or doing of something is broken down in clearly identifiable steps. And each step is carried out by a separate worker, or group of workers, who need only to be familiar with the skills of performing that one step. And this is what is normally meant by division of labor.” (Franklin, 1989)

We can see this distinction between holistic and prescriptive methods in the creative arts as well. As a musician I have been both a musical auteur and a member of an orchestra. As a musical auteur I develop the concept or idea, put together a cast or ensemble of people to participate in the execution of these ideas (or decide to do it myself), I build the necessary hardware, software, instruments, specialized mallets, surfaces, and possibly a new method of notation suited to the work. I think about lighting concepts, costume design, venue configuration, documentation strategies and maybe most importantly, where we will gather to have a drink after the show is over! This is a clear example of a holistic form of crafting a piece. Even though there are people who’s job it is to execute certain specific tasks throughout the course of the project, these people are also included in the decision making process, they are responsible for developing their own work flow and bringing their own manners of expertise to the creative process while the process is still being developed.

As a member of the orchestra, I am told to sit, read and play my part, and respond accordingly to the information dictated by the conductor (who plays the part of the auteur, but for me, this is a rather weak cup of tea). I am considered to be breaking the machine, if I interrupt the rehearsal process to ask why we decided to take this and this particular section at a new tempo, or to ask the front desk of my section for advice on how exactly one should execute a particularly gnarly and technically difficult passage of notes on the page. It is my job only to display efficacy of technique and to comply with the directives of the person standing at the podium. I am not to find my own path through or to define what my role could be in this large ensemble. I’m not even supposed to pull or push my bow in a different direction to my colleagues, even if it is somehow more efficient or more comfortable or even more musically satisfying to do so.

“There are designs for discipline and compliance. For order, and obedience. And I think that that is really the most important thing. These technologies need to be prescribed sufficiently clearly that each step is carried out correctly so that it fits into the next step. And when the work force, works in an atmosphere of such prescriptive technologies, they become acculturated to them-they enter into a milieu. You enter into a culture in which external control and internal compliance is considered normal and necessary. And eventually, everybody thinks there’s only one way of doing this. It is a seed bed for orthodoxy.” (Franklin, 1989)

“And so I think, while we should not forget, in any way that these prescriptive technologies were exceedingly effective and are exceedingly effective, and efficient, they come with an enormous social mortgage. And that mortgage is that we live in a culture of compliance, that we are on and on through these conditioned, to accept orthodoxy as normal, that there is only one way of doing it.” (Franklin, 1989)

So what are some other ways of “doing it”?

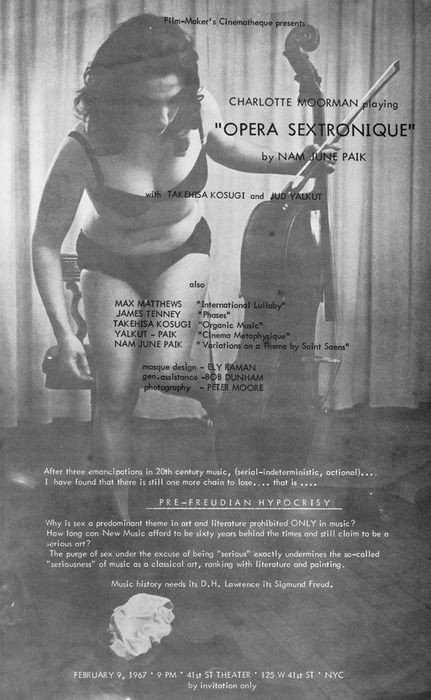

I find the multi-media collaborations between Nam Jun Paik and Charlotte Moorman nicely exemplify a holistic creative model which bucks the normalization, commodification, and general lulling factor that Western classical music had easily acquiesced to, in the 1960’s-70s. Paik and Moormans most infamous collaboration is Opera Sextronique, in particular, their 1967 New York performance at the Film Maker’s Cinematheque where Paik and Moorman were arrested, and Moorman was later charged with indecent exposure.

Opera Sextronique is a collage of classical music, provocative costuming (or lack there of), politicized props and quotidian movements extended by tactics of time based manipulations. This is an “opera” in 4 acts –which Paik calls Arias.

In Aria 1, Moorman appears on stage clad in an “electric bikini” – adorned with tiny 6V light bulbs which are controlled by Paik via Remote Control. The sound of a gong is heard and Moorman, slowly and patiently walks the short length of 8 feet over the extended course of 5 whole minutes, finally taking her seat center stage. When she reaches her seat, Paik joins her onstage to accompany her in a few excerpts of Jules Massanet’s Elegy- all the while, the lightbulbs of Moormans electric bikini are blinking on and off.

In Aria 2, Moorman now appears onstage topless, wearing a long formal skirt. Moorman picks up her cello to play sections of Brahms’ Lullaby. After Charlotte plays 2 measures of the Brahms she stops to pull out various everyday items from an old suitcase which is stationed next to her.

She puts on Masks, sunglasses, hats, - plays the cello with a “prepared bow” made of a bouquet of flowers – and after a few iterations of this back and forth between playing the Brahms and handling the suitcase of props.

Paik enters the stage, disrupting Moorman’s domesticated- if not a bit manic- ritual, and places a battery powered propeller on each of her nipples, turning her breasts into toy helicopters.

There are two more Arias, where Moorman plays the cello nude from the waist down while wearing a football uniform-and finally, and Aria where she performs completely nude and plays a metal bomb as if it were a cello.

Paik and Moorman expand their view of the ‘necessary’ materials needed to perform an Operatic production and remove the label of “Aria” from it’s expected placement on the throat of long winded dying , putting this label instead onto a blinking bikini, a whirring peep show, a neutered bombshell. Opera Sextronique is an example of how Paik and Moorman question the “technology” of traditional Western Opera and the system which created an audience so lulled into certain expectations by this technology that they refuse it outright and put those responsible behind bars.

TV Cello was a project that Moorman had proposed to Paik.

“What I expected him to do was go buy a student cello, an old one at a pawn shop, and cut three holes and insert the tubes, elongate the wires, and I’d have a TV cello. That’s not what he did at all” (Moorman, 1982)

Instead, Paik built a monstrously futuristic cello. He removed the tubes from three sets of TV’s and mounted them inside plexiglass boxes – Two large cabinets with one smaller cabinet stashed in between. He completed the physical metaphor of a cello with a strip of rectangular plexiglass attached to the top as a fingerboard and peg box and strung up the boxes with a single string, which was amplified and disturbed the pure projection of the image on the televisions’ screens.

Moorman was responsible for the live performance elements of the work but it was her own sculptural contributions to the piece which pushed Paik’s concept from being a rather blunt translation from classical music object to visual technology object - to a more complicated blurring of these two worlds. She insisted that the TV cello should have a bridge placed on one of the screens to help keep the strings taut. Later, additional strings and tuning pegs were added to the instrument which allowed Moorman to have more flexibility and control of her sounds – making the instrument more musically viable and strengthening the TV Cello’s performative capabilities by adding to the already rich visual landscape, a more sonically adaptable performance opportunity.

Humanizing technology

Paik’s personal interest in humanizing technology along with his own technological skill set, lay the conceptual and practical foundations for this period of their collaborative work, while Moorman’s performance with these objects vivifies Paik’s concept by connecting it to the human body and activating the technology in the performative space.

In these two works there is a common theme of radically humanizing an artistic space by altering the tools, and therefore the tasks, of cultural institutions which had become preoccupied with fulfilling the proper ways of “doing it” which were dictated by artistically prescriptive technologies such as the Opera house or the virtuosic soloist. In Opera Sextronique Paik and Moorman disrupt the conservative classical concert space with loud, brash, and insistent acts of sexually ecstatic play while with works like TV Cello, the duo super-imposes two culturally accepted tools, a television and a cello, to create a performance that insists that these technologies be used not as methods of pre-packaged forms of entertainment but as possibilities for pushing forward imagination and exploration in cultural institutions which were threatened (and are still threatened) by their own complacency.

Tools and Tasks of Multi-Media artists

I previously invoked Ursula Franklin’s notions of “tool” and “task” - and I wanted to give some examples of wonderful artists who I think use these notions of tools and tasks to push against the prescriptive rules of the technology which they use to create their art.

For the setup, here, once again, is Ursula Franklin :

“I would think that finally, I would like to look in terms of the real world of technology into the relationship between tool and task, because there’s always a relationship between what you want to do and what you have to do it. The technological order provides a very wide spectrum of particular tools, be these organizational, be they administrative, or be they merely mechanical or electric. But tasks tend to be structured, often by the newest available tool. And it then looks as if the new tool is not only the best, but very often the only tool. And we know it in our own lives in small things. If you get a new kitchen appliance, you begin to slice and dice and beat in ways you’ve never done before, and you’ll begin to forget that there are other ways to prepare a meal. And eventually, you never do it. And by the same token, if your lab gets an electron microscope, it’s amazing how many problems have to be looked at, at the highest possible magnification. And you find great difficulty and I find great difficulty to persuade students to look at anything under an optical microscope, or heaven forbid a magnifying glass. So the tool structures the response. And they can be a real tyranny of tools, and one has to be quite mindful of that.” (Franklin, 1989) (Lecture #5)

Examples

Here are some examples of creative and unexpected ways that artists have re-conceptualized the use of tools in an effort to battle the tools own tyrannical potentials.

Paul DeMarinis: Firebirds (2004)

The voices of Roosevelt, Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin, emanate from 4 separate bird cages placed throughout the gallery space. These voices are not made audible through the expected tool of a loudspeaker, but rather through the flickering flames of a Bunson burner behind the metal bars of the bird cage. DeMarinis describes:

“Oracular flames kept captive within birdcages recite speeches of some politicians of the twentieth century. Gas flames, suitably modulated by electrical fields can be made to act as omnidirectional loudspeakers of surprising clarity and amplitude.”

DeMarinis uses the fiery tools of the scientists laboratory to create the medium through which these voices are heard, and traps these tiny dangers inside the most futile and domestic of jail cells. In Firebirds, I find, that DeMarinis’s use of these unexpected tools (and their relationship to one another)puts forward an ideological metaphor. The words of leading public figures who’s capitalist, fascist and totalitarian speeches do have the ability to spread (like fire) -can also be choked by cutting off its source of fuel, who’s flux is maintained by the everyday person. Or perhaps it is the other way around, and that as long as the fuel is provided by the owner of the cage - the parrot within the confines of its bars will be able to mimic back choice phrases which through aural osmosis become it’s main talking points.

Nolan Lem: Menagerie (2020)

In Menagerie by multi-media sound-artist Nolan Lem, the public enters a room permeated by the polyrhythmic clicks of 50 fabricated automatic rifle triggers suspended from the ceiling. Lem describes the relationship between the tools used and the artistic-political directive of his piece:

“Inspired by the collective behaviors associated with biological swarms, this piece repurposes the deconstructed gun trigger as an autonomous sound object to evoke the repetitive nature of gun-related violence. Using statistics taken from the occurrence of firearm-related deaths from each US state, fifty custom fabricated automatic rifle (AR) style triggers are subject to various self-organizing and behavioral algorithms where they align, synchronize, and devolve to reveal the emergent polyrhythms inherent in American patterns of violence. The empty gesture the unloaded, cold-clicking trigger is emblematic of the listlessness of political action and redress. In this piece, this sound is used as a medium through which the trigger swarm aggregates and composites sonic mass.” (Lem, 2019)

In Menagerie, Lem uses the tool of the gun trigger to create a sonic metaphor which reacts against the triggers intended use of silencing its victim. The art object which he creates amplifies the disparity between the guns symbolic identity as a tool of protection and the tool’s societal implementation of violence-based control.

“Positioned in the glass enclosure like a flock of birds, the triggers call to mind the taxonomical habitats often displayed in menageries and natural history museums. The kinetic mechanism itself problematizes the nature of intention and premeditated action associated with gun violence where the act of “pulling the trigger” has taken on an autonomous role independent of human engagement and volition. By interrogating the cultural anxieties surrounding firearm ownership, this installation points to a future in which technology, automatization, and a persistent military-industrial complex have created the ideal habitat from which these mechanisms can reproduce, proliferate, and swarm.” (Lem, 2019)

Sivan-Cohen Elias: How to Make a Monster

The domestic technologies of a typical kitchen scene are transformed into a dystopian laboratory setting where a “monster” is mixed into creation, parts of a homunculus or possibly human form are mashed together and the entirety of the laboratory system responds with the reverberated efforts of the creature coming slowly to life. In the beginning the performer is reduced to similar, modular parts as the monster they aim to create - hands (big and small) and feet which navigate the terrain of metal mixing bowls, colanders, styrofoam balls and bits of string. The performer and monster move with non-seeing insecurity in the way they traverse the landscape, yet the dynamics of control are visible through the use of the tools available only to the creator on the laboratory’s table.

The monster is rendered by dismantling the useful modular and removable parts of the performer(creator), and depositing them onto the alchemical surface of the laboratory, in what I personally read to be a metaphor for the biologic selection of dominant genes.

When the performer is revealed in their full human form - they are also portrayed as kind of “other” - the costuming is not that of a scientist in lab coat with spectacles and heat-proof gloves, but that of a futuristic cyber-punk hacker, who uses what has been made available to them in this dystopian scene, to create their soon-to-be companion from the sterile remains of the modern-day kitchen.

There is both tenderness and control - domination and acceptance of the creature as it gestates and learns how to become a part of it’s own environment, sometimes in an unwieldy and unpredictable manner (though always controlled through the realms of puppetry by the creator). Through the monster’s screams to life, the creator gently rocks and comforts it’s creation, giving the piece an additional layer of an uncertain maternal relationship between human and “monster”

In “How to Make a Monster”, Cohen-Elias and Huang supplant the feminine associations of domesticated kitchen tools with the Frankenstein myth - a kind of birth (or re-birth) which materializes not in the form of a salad or cake (as the tools on the table might imply), but into a chattering, screeching imp - equipped with only the necessary parts of a human form which allow it to experience its fabricated universe. But of course, the monster is not satisfied until it can have control over the bodily form of the creator, and exerts its dominance as soon as it has legs!

The benefits of using the Tool in the “wrong” way

I’d like now to briefly consider some benefits to mis-using technological tools

Yasunao Tone’s Wounded CD

In Yasunao Tone’s works for Wounded CD, the artist embraces glitch and the malfunctioning of a technological object to create a whole genre of music, which is still performed (and employed through different mediums) today. In 1997 Tone issued the album that you are hearing now titled Solo for Wounded CD. Tone describes his extended technique in a note from his performance at the Lovebytes Digital Art Festival:

“In the fall of 1984, after reading a chapter on digital recording in a Japanese book, I wondered if it was possible to override the error-correcting system of a CD player. If so, I could make totally new music out of a ‘ready-made’ CD. I began by simply making pinholes on a bit of Scotch tape, which I stuck to the bottom of a CD. The Scotch tape not only changed the pitch and timbre, but also the speed and the direction of the spinning disc. To my surprise, the ‘prepared CD’ seldom repeated the same sound when I played it again, and it was very hard to control. The machine’s behavior was very unstable and totally unpredictable; I therefore thought it would be perfect for performance.” (Tone, 2002)

Through physical manipulations of the CD and the forcefully performing the different functions of the CD player, Tone encourages and extracts an exhilarating tangle of sonic results of the tool’s misuse.

Marino’s AUTOPROCESS

In this piece of my own, written for composer-performer Max Murray I wanted to set up a two sister-systems of exhaustive and impossible processes that would pit performer against machine. To set things up, I sat down at a MIDI keyboard and attempted to play a simple diatonic scale over and over and over again until my fingers were exhausted and cramping. At which point, I pressed the “Input” button and allowed the MIDI data to be recorded into a notation software program which was ill-equipped to understand the rhythmic complexities performed by my exhausted fingers. This software automatically quantized my performance, understanding my fluctuations in tempo as inaccuracies, and according the programs quantization logics, washed away the human qualities of fatigue which I interpreted as a conceptual point of intrigue, thus rendering my painful performance into an absolutely inane series of ascending etude-like scales through the voice of the my preselected MIDI TUBA instrument.

In System one - I printed the results of the softwares quantized notation and handed them over to performer Max Murray. I asked him to try to perform in “perfect unison” with the MIDI TUBA playback, a feat, which is actually just impossible. As soon as Max began the playback track, he was off the mark- the tempo is too fast to articulate each note in unison with the digital tuba, the physical taxation on the hands and lips gets harder and harder to manage with accuracy as time goes forward - not to mention, that there is absolutely no place in the five and a half minute piece for Max to breathe. We recorded his rigorous efforts and after many gifted pints of “please forgive me” beer I introduced his recording to the second system.

In this system, I wanted to put the exhaustive task back into the gears of the machine which had tech-washed our mighty, yet flailing human efforts. This time, I asked my computer to play back the video recording of Max’s performance in ever increasing numbers one layered on top of the next, on top of the next until 11 simultaneous videos had been launched. My laptop’s fan started spinning out of control after the 3rd video began and the result after 11 launched video renderings is a sputtering, glitching, completely blown out document of the computers inability to handle the amount of information is was tasked to process - exactly the same problem that Max was confronted with in the previous system. From an audience standpoint, this piece is awful to watch and to listen to, but from a conceptual angle, I found that this piece crudely navigates a feedback loop which prides itself on failure, and equally illuminated the physical boundaries of both a human and a machine.

Roman Singer’s Punkt

This is a classic. And I place it here because maybe we need a little break before the final section.

This is Roman Signer’s performance piece “Punkt” in which he de-fangs a widely recognizable tool of war in order to make a painting. Enjoy!

Pseudo-realties

In this final section I wanted to bring back the words of Ursula Franklin and her ideas on the different types of realities that we as humans experience. She outlines different constructs of reality and defines them in her writings “The Real World of Technology” a publication based on and expanding upon her lecture series:

“The first level of reality is that nitty-gritty stuff, the direct action and immediate experience, the sort of thing I like to call vernacular reality. It’s bread and butter, soup, work, clothing and shelter, the reality of everyday life. This reality is both private and personal but it is also common and political…. I will call extended reality that body of knowledge and emotions we acquire that is based on the experience of others. Here we have all those experiences that we would have had, had we been there. These are the experiences of war, of depression, of old age, of foreign travel….. extended reality includes also artifacts - which we try to make part of our own reality because we like to draw on that continuity, on that experience of the past….over and above this, we live with what I call constructed or reconstructed reality . Its manifestations range from what comes to us through works of fiction to the daily barrage of advertising and propaganda. It encompasses description and interpretations of those situations that are considered archetypal rather than representative. These descriptions furnish us with patterns of behaviour… Finally there is projected reality - the vernacular reality of the future. It is influenced or even caused by actions in the present. Heaven and Hell or Life after death were - and are still - for some people projected reality. Today there’s also “the future” itself, the five-year plan, the business cycle - and these can influence people’s actions and attitudes as much as or more than the price of bread of the level of wages.

…All of the realities I mentioned… have been profoundly affected an distorted by modern technology…

In terms of the realities that we have discussed, the message-transmission technologies have created a host of ‘pseudo-realities’ based on images that are constructed, staged, selected, and instantaneously transmitted… The images create new realities with intense emotional components. IN the spectators they induce a sense of “being there” of being in some sense a participant rather than an observer. There is a powerful illusion of presence in places and on occasions where the spectators, in fact, are not and have never been.” (Franklin, 1999) (p.34)

“The selective fragments that become a story on radio and television are chosen to highlight particular events. The selection is usually intended to attract and to retain the attention of an audience. Consequently, the unusual has preference over the usual. The far away that cannot be assess through experience has preference over the near that can be experienced directly.” (Franklin, 1999) (p.35)

“Because there are now technical and economic means of creating these pseudo-realities of images and exposing a large part of the globe to them, experience realities and their dynamics have changed, and keep on changing.” (Franklin, 1999) (p.28-35)

I wanted to include this lengthy quote from Franklin because it outlines many of conceptual underpinnings of my piece Nice Guys Win Twice, which I made in collaboration with Constantin Basica and the ensemble SCENATET.

Nice Guys Win Twice is a work for 10 performers, live electronic sound and video landscape, where the ensemble is sent to perform absurdist rituals surveying the validity of imagined facts through a projected filter of dreaming and pulsing webs. Ritual incantations of the everyday are incited as reminders of our habits and the ways in which small changes in the type of information that we ingest, can affect our daily outlook. The video landscape shivers and twirls with ocular tricks, faking tremors and spin outs of the stationary objects on stage. The performers switch voices, learn gestures and blur their identities to a conglomerate whole. In a flight of fantasy a school of flying fish airlift themselves above the stage, crashing into one another, raising and lowering themselves into the performance space to create a moveable floating wall of chaos and charm. We experience together, the suspension and release of our disbelief as the performance teaches us how to distrust our body’s acceptance of its own aural-ocular information and to adapt to the new way that our senses function and misinform us from within the vibrating dream world.

Nice Guys Win Twice travels through the many spectacles of the everyday uncanny. The performers shuffle through micro-managed mundane gestures as a form of choreographed self-care, render the language of political dramas into sputtering piles of abstract glitch and push around projections of everyday technology which slowly build up a mediated veneer of the real which keeps us at safely at our desks away from the action.

In Part One - the performers are sequestered to small illuminated boxes onstage and asked to repeat combinations of everyday gestures, such as touching your toes, adjusting your glasses, lifting your arm, or pointing. These gestures are organized into rhythmic frameworks and repeated in various combinations.

In Part Two - SCENATET stages a political address, modeled after the most recent State of the Union Address in the US. The language of this political spectacle has been filtered, removing all of the vowels from the language, and making percussive the remaining consonant letters. By altering the language and adding to this repeated physical gestures, the line between political drama and cult following begins to be blurred.

In Part Three - The ensemble pushes cardboard boxes around the stage. On these boxes is projected different everyday video footage - making the boxes look like moving television screens. They move the boxes around in different configurations and eventually build up a stacking wall of blinking, glitching television sets.

This piece is about the difference between building and fabrication. The realms of the real vs the realms of the virtual. The difference between memory and nostalgia. An interpolation between the home space and the screen space. Transforming the entirety of the theater from a stage, to a screen, to a tiny domestic habitat for a fish. Can the physical be swallowed by the digital?

References

- Burrows, J. “A Choreographer’s Handbook”. Routledge. 2010.

- Franklin, U. “The Real World of Technology”. CBC Massey Lectures. 1989.

- Franklin, U. “The Real World of Technology”. CBC Massey Lectures - Revised Edition. House of Anansi Press. 1999.

- Lem, N. “Menagerie”. Description of artwork in Nolan Lem’s website. 2019.

- Moorman, C. “Charlotte Moorman in conversation with Vin Grabill”. VHS, CMA.. 1982.

- Tone, Y. “Wounded Many at Lovebytes”. program notes from Lovebytes Digital Art Festival. 2002.