Unit 5: Audiovisual Performance

Synopsis

Audiovisual Performance

Audiovisual

I personally find most combined music-video art problematic. It seems to me that the sound and images often compete for my attention. If I pay attention to what I am seeing, I often miss what I am hearing, and if I try to concentrate on the music, the images can often be an irritating distraction… Max Mathews (Coulter, 2010)

It may seem odd to begin with a quote that apparently goes against the very subject of this unit. But I consider Max Mathews’s stance on music-video art—which is shared by many others—a great starting point for our discussion. It is natural for those with sight and hearing to have a multimodal perception of ‘audiovisual phenomena’ in the world because we experience events as a combination of sensations (Lachs, 2021). For example, seeing a glass drop on the floor and break without hearing its effect would be a cause for alarm to our brain. However, in art, the disciplines that communicate with our eyes and ears have long been separated. Even though there is a rich history of music and visual arts coming together, especially since the dawn of the 20th century, there are still many theories and debates today about what constitutes valuable, successful interactions between sounds and images. So Mathews’ perspective is not far-fetched, and the idea that sounds and images compete for the viewer-listener’s attention is crucial to audiovisual performance. As we will see through a number of theoretical frameworks for audiovisual analysis, it is precisely this perceived competition, or sometimes the lack thereof, that allows sounds and images, or music and video, to merge into a whole that is more than the sum of its parts. Fluxus artist Dick Higgins talked about the conceptual fusion (Higgins, 2001) of divergent media in a work of art when defining the term intermedia. His idea is valid in audiovisual contexts where we may not be able to perceive the sonic and the visual elements as a hybrid unit — as in the case of Max Mathews — but where the coexistence and collaboration of sound and image can drive the conceptual thread of a work in ways that maybe would not have been possible through a single medium.

Performance

The term performance indicates, on the one hand, the involvement of one or more persons (or other entities with agency) that present a work of art to an audience. On the other hand, the concept of performance signals that the work takes place in real time. While we can discuss performance from many perspectives in different disciplines—music, theatre, performance art, and other forms of entertainment—the liveness aspect is essential to our topic because it can grant an audiovisual work the state of presence. Moreover, the notion of liveness in multimedia or audiovisual performance is particularly interesting because of the involvement of technologies that have been long associated with processes of recording and reproduction.

The debate on what constitutes liveness in performance is often attributed to two theorists with opposing views on the subject. On one side is Peggy Phelan’s book Unmarked – The Politics of Performance (Phelan, 1993), which advocates for the ontological irreproducibility and ephemerality of performance. On the other side, Philip Auslander’s writings in his book Liveness: Performance in a Mediatised Culture (Auslander, 1999) problematizes the concept of live performance in the context of mediatized events. He asserts that there are in fact no clear “ontological distinctions between live forms and mediatized ones” (Auslander, 1999) and underlines that the concept of live performance has appeared as a consequence of the ability to record and broadcast performances using technology.

In the chapter titled The ontology of performance: representation without reproduction, Phelan postulates: “Performance’s life is in the present. Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance” (Phelan, 1993). She adds that “Performance implicates the real through the presence of living bodies” (p. 148) while positioning her theory in relation to contemporary performance art. This is a crucial point that informs my own theory later in this unit. Philip Auslander argues that live performance today has become almost indistinguishable from its mediatized counterpart. The word mediatized, which he borrowed from philosopher Jean Baudrillard, refers to events that are disseminated via mass media such as television, audio or video recordings, and other reproduction technologies (e.g., live streaming, the Internet, etc.). He writes: “Live performance now often incorporates mediatization such that the live event itself is a product of media technologies. This has been the case to some degree for a long time, of course: as soon as electric amplification is used, one might say that an event is mediatized. What we actually hear is the vibration of a speaker, a reproduction by technological means of a sound picked up by a microphone, not the original (live) acoustic event. Recently, however, this effect has been intensified across a very wide range of performance genres and cultural contexts, from the giant television screens at sports arenas to the video apparatus used in much performance art.” (Auslander, 1999)

Rosemary Klich and Edward Scheer, too, point out in their book Multimedia Performance (Klich et al., 2012) that “it is not the distinctiveness of the different elements (live v mediatized) that matters; rather, it is the real-time interaction and experience of these elements that is key. And this interaction constitutes a live experience of performance, which, however mediatized and pre-recorded, may never be exactly reproducible” (Klich et al., 2012). This reconciliatory view of performance that involves media elements is also the one I subscribe to as will become more apparent in this unit.

In his book Digital Performance (Dixon, 2007), Steve Dixon expands on this topic and, in relation to live multimedia theatre, writes that the audience’s mode of perception of live actors versus film or video projections is different. This becomes noticeable once the live performers exit the stage, leaving the projections in an obvious non-live state (p. 129).

While the video performer in Neo Hülcker’s A body essay. Fiction actually is of a different nature than the live performers on stage—even with a different size and background—we perceive them as a group. The question of live versus prerecorded video is less relevant. But once the live performers disappear in the dark and we are left with the video alone, the nature of the prerecorded performer suddenly shifts into focus.

Similarly, in Michael Beil’s BLACKJACK, the live and virtual performers seem to be merged into the same performance frame due to the video feedback effect. But the interplay between live action and live recording, as well as immediate and delayed playback, alters how we perceive the liveness of each layer.

Audiovisual Performance Examples

With the two constituent terms of this unit—audiovisual and performance—briefly covered, let us view-listen to a few contrasting works that fall under the umbrella of audiovisual performance.

As exemplified above, the manifestations of audiovisual performance can vary quite radically in form, aesthetics, technology, and presentation. Thus, before going forward and discussing current practices associated with audiovisual performance and a new subgenre that I will propose, it is worth looking back at the historical lineage of audiovisual art forms.

Audiovisual Lineage

Sound-Color Mapping

Early audiovisual correspondences can be traced back to the ancient Greeks, but it was in the 18th century when Isaac Newton proposed relationships between the wave properties of light (color) and those of sound (musical pitch). Others followed this idea in the next two centuries and linked musical tones to colors.

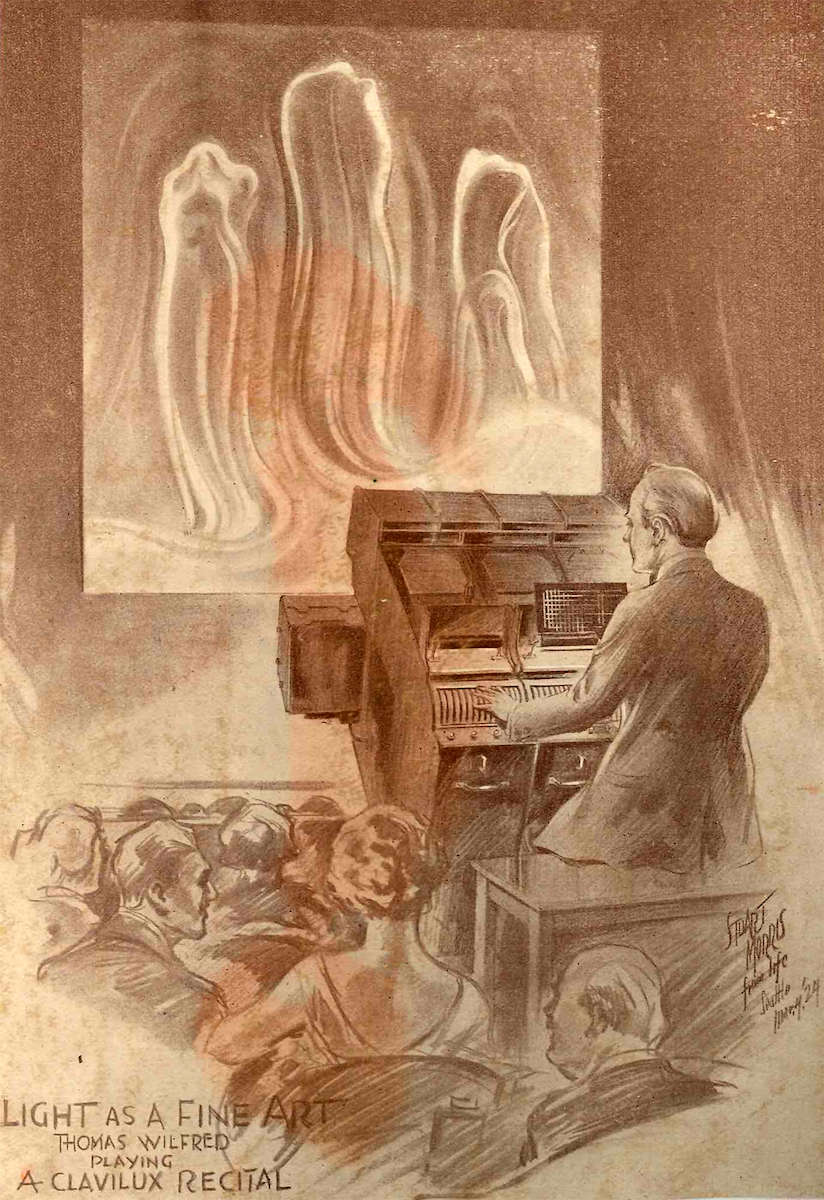

Some of these scientists and artists also created contraptions to achieve the correlation between light and sound, named color organs. These were instruments based on light, in various shapes and sizes, often modeled after the harpsichord, with the purpose of realizing direct ‘conversions’ from music to colored light projections.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/85/49/854937e8-294b-4b9f-88ad-d9609272a4ef/1_wilfred_sitting_at_the_clavilux.jpg)

Alexander Scriabin included such a device, called clavier à lumières (keyboard with lights), in his score for the symphonic work Prometheus. Preston Millar created the Chromola, a color organ to perform the part, although its appearance in performances was rarely documented. Anna Gawboy and Justin Townsend recreated it at the Yale School of Music in 2010.

Visual Music

Visual music is perhaps the ancestor of all audiovisual art practices today. Even before technologies such as film, video, and digital media, visual music existed through intersections between music and the visual arts. Painters like Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Jackson Pollock, or Mark Rothko sought to transfer musical parameters, rhythm, form, and texture into their visual language. But what we mostly refer to as visual music today began as a form of early film, namely abstract or absolute film. This was a departure from traditional narrative cinema concerned with structure and form rather than tangible objects or meanings. The idea was similar to what the aforementioned painters had attempted: to transpose musical structures and behaviors into moving image. In essence, these were audiovisual works in which the visual and musical layers were coordinated as a single entity. Some of the first visual music works consisted of non-figurative and geometric shapes moving in rhythmical patterns. Later, abstract shapes started being choreographed to classical music and other types of music.

Historically, visual music can be divided into the following stages:

- non-moving visual music (painting);

- non-sounding visual music (silent film);

- visual music (moving image with sound).

In most of these examples there is a very direct, one-to-one rhythmic correspondence between the visuals and the music. This is related, although not equal to synesthesia (joined perception), which cannot be ignored when talking about visual music. Synesthesia is a rare but real condition in which one sense, such as hearing, concurrently triggers another sense, such as sight. People with synesthesia might smell something when they hear a sound, or see a shape when they eat a certain food. Wassily Kandinsky, for example, could see colors while hearing music, and hear music when painting. Visual music is thus linked to synesthesia in its attempt to either 1) recreate the types of crossmodal connections between sight and hearing experienced by some synesthetes artists, or 2) to design what psychologists John E. Harrison and Simon Baron-Cohen call pseudosynaesthesia (Harrison et al., 1997) as an immersive effect. Aimee Mollaghan in The Visual Music Film (Mollaghan, 2015) describes the metaphor as pseudosynesthesia: “[…] the audiovisual relationship is functioning not as direct translation of sound into image but as an allegory or correspondence” (p. 12). She gives Norman McLaren as an example, who was purportedly a synesthete, and notes that “the colour–sound associations he uses are pseudo-/culturally synaesthetic associations” (p. 12). Mollaghan then calls synaesthesia a “popular malapropism in relation to the visual music film” (p. 13) since the audiovisual correspondences are generally artificial, constructed, and meant to evoke the feeling of synesthesia. Nevertheless, this type of one-to-one, synesthesia-like correspondence is perhaps the most recognizable feature of not only visual music, but audiovisual genres in general. In some works—especially early visual music as in the examples above—pseudosynesthesia pervades the entire structure as the single or most important process of the audiovisual unfolding. However, the predictability of this process has the tendency to become fatiguing and may lead to what is known as Mickey Mousing: a pejorative term in film that comes from cartoons, and which refers to music that attempts to strictly imitate the visual action. [For more on Mickey Mousing and gesture representation, see Unit 12] Therefore, many artists tend to make use of this type of direct correspondence rather sparingly, as a compositional technique that yields a powerful effect.

The premise of visual music—a music for the eyes—has had ripples all the way to the present day. In Jessie Marino’s first part of Nice Guys Win Twice we find a type of visual music that does not involve film, video, or recorded audio. The visual movement is fully realized by performers on stage with added elements of lighting design. What we see is a complex contrapuntal visual music in which the parts are scored for a plethora of bodily gestures and actions. Some of these also generate sounds due to the interaction between body parts, between bodies and objects (chairs, floor), or even subtle vocalizations caused by the actions.

Video Art

Another art form that has been influential for today’s audiovisual performance is video art. Although the video medium is a technology that was popularized only 50 years ago, it has already travelled a long journey in the arts. Video art was born in the 1960s at the intersection of television and Fluxus. It swiftly reached its pinnacle by the 1980s and settled as an established genre in the 1990s once with its institutional acceptance. Nowadays, the genre is rather theorized and historicized than practiced because of the obsolescence of the original analogue medium, but the principles of video art have spread and evolved into various audiovisual genres, which is why it is useful to observe some of its characteristics.

First, video art has been an audiovisual genre from the start. Musicologist Holly Rogers shows that, before video’s arrival, early “audiovisual practices, such as lantern shows, music theatre, opera, synesthetic experimentation, early direct film, and so on, were intermedial primarily at the level of reception” (Rogers, 2013) and video made it possible to achieve audiovisuality at the level of production, thanks to the medium’s abilities to record sounds and images simultaneously. Rogers says: “With the new medium, artists were able to include sound in their work in order to push the boundaries of current creative concerns. But video also presented composers with the opportunity to visualize their music” (p. 1). Many pioneers of video art were in fact musicians (e.g., Nam June Paik, Steina Vasulka, Robert Cahen, Tony Conrad, Bill Viola), which established the practice as a “highly musical genre”, in Holly Rogers’ words.

Bill Viola explains, too, how video is a closer relative to sound than to film, because the camera (“an electronic transducer”) transforms “physical energy into electrical impulses” comparable to a microphone, whereas film relies on a mechanical/chemical process. Therefore, video developed as a close relative to audio technology and its editing techniques (Viola quoted in Rogers 2013, p. 18).

Second, video offered artists a platform for experimentation unhindered by the conventions and traditions of fine art. For this reason, many women took the opportunity to express their work through video. Michael Z. Newman, in his book Video Revolutions (Newman, 2014), explains that between the 1950s and the 1990s—before digital video was commercialized—the medium moved away from its original correlation with television and became an opposition to it and to its live broadcasting nature (p. 18). Newman shows that video, in its infancy, was perceived as a “revolutionary solution to many of the perceived problems of television”, since it was not governed by “economic or ideological” constraints (p. 19). This type of revolutionary use of video has lost its significance today because of the ubiquity of the medium in various cultural forms, but we’ll see that composers working with video in the context of music performance share a similar excitement for the freedoms and possibilities that the medium brings to the abstract world of music.

Lastly, the concept of performance was paramount in video art. As Helen Westgeest clarifies, video was used in the 1970s as “recordings in performances” and as “recordings of performances”, both of which were referred to as video performances (Westgeest, 2016). In the former category belong works by Carolee Schneemann, or Dan Graham, which integrated the immediacy and intimacy of the video medium into live performances. Vito Acconci’s Corrections (1970) and Joan Jonas’s Vertical Roll fit into the latter category, which transcended live bodily performances into video recordings for the purpose of further manipulation. This way, the performance conceded its physical liveness to a virtual version (Westgeest 2016, p. 45-60). Both these types of performance-based video art have remained influential in the works of media artists and audiovisual composers today.

Music Video

Historically concurrent with the development of video art, the medium of video was used to establish another audiovisual genre which delivered content to a wider audience, and is very much alive today: music video.

What is compelling in music video, as Carol Vernallis puts it, is the remediation of visual material by combining, juxtaposing, or appropriating imagery from different sources in a manner similar to how poetry relies on figurative language (Vernallis, 2013). Mathias Bonde Korgsgaard wrote that music videos “both ‘visualize music’ and ‘musicalize vision’” (Vernallis, 2013) which is a type of symbiotic relationship between music and video. Furthermore, Michel Chion wrote that music’s power to displace time and space is taken a step further in music video, where only sporadic sync points are necessary to keep the audiovisual medium together, but the image is allowed to “wander at will through time and space” (Chion, 1994). This sense of autonomous audiovisual layers that come together at necessary sync points is different from what visual music proposed. Instead of near-continuous audiovisual correspondence, the music and the moving image act as quasi-independent entities here. Their relationship is different from one music video to another depending on the visual content, which can be generally assigned to one of three main categories:

1) videos that portray the music performance itself;

2) videos that present an independent narrative from the music;

3) videos that exhibit a specific concept (such as dance, travel, abstract imagery, etc.).

While visual music, video art, and music video have had different aesthetic, cultural, and socio-economic starting points and features, there are many overlaps in terms of how they treat music and moving image as partners in a joint artistic endeavor. In the following part of the unit we will look at a few theoretical frameworks that provide insights into how sounds and images work together in these art forms and other audiovisual manifestations.

Theoretical Frameworks

Parallelism and Counterpoint

Sergei Eisenstein, pioneering director and film theorist, proposed that sound montage be developed along the lines of visual montage and that the two be asynchronous to one another. In the Statement on Sound (Eisenstein et al., 2014), Eisenstein together with Vsevolod Pudovkin and Grigori Alexandrov postulated that sound works either in parallel with or in counterpoint to the visuals. By parallel they meant that the sound is essentially voicing what the image is showing. This is crucial for dialogue and sound effects going along with the image in precise sync, but not desirable for music as it would be an aesthetic doubling. In counterpoint there is a fruitful disjunction between what is seen and what is heard. We know from music that counterpoint is the independence of musical voices or lines that nevertheless still make sense together. However, while in music there are three different types of motion (parallel, contrary, and oblique), in film music only the ‘contrary motion’ is considered to be counterpoint to the image. Thus, we should note that ‘parallel vs. counterpoint’ is not the same thing as ‘congruent vs. incongruent’, because parallel is seen as negative, while counterpoint is the ideal. Congruent/incongruent may be used to describe both parallelism and counterpoint separately.

Michel Chion is dissatisfied with the notion of audiovisual counterpoint and prefers to call it audiovisual dissonance. He finds that, beyond the issue of quasi-misappropriation of the musical term ‘counterpoint’, the problem is that in film sounds are considered based on their stereotyped meaning rather than intrinsic sonic qualities: “So the problem of counterpoint-as-contradiction, or rather of audiovisual dissonance, […] is that counterpoint or dissonance implies a prereading of the relation between sound and image.” (Chion, 1994) He exemplifies this with Jean Luc Godard’s First Name: Carmen that opens with a Paris metro shot and sound of seagull cries; he calls on the fact that critics interpreted this as counterpoint (urban setting vs. seashore), when in fact the sound itself, stripped from its meaning, may not have created an opposition to the image (p. 38).

Let us examine two examples of audiovisual performances that fit these two paradigms.

Parallelism

Counterpoint

Added Value & Synchresis

Michel Chion’s theories of sound-image relationships primarily address the world of film, but they are so well thought out and generalizable that they can easily be applied to other genres. And, indeed, Chion is very often cited by other researchers working toward audiovisual theories. Although many of his theoretical points are worth considering, I mention here because of lack of space only two aspects of sound/image relationship from his book Audio-vision: Sound on Screen (Chion, 1994).

The first chapter, The Audiovisual Contract, is based on the audiovisual illusion Chion calls added value: “Sound shows us the image differently than what the image shows alone, and the image likewise makes us hear sound differently than if the sound were ringing out in the dark” (Chion, 1994). The concept posited by Chion is that when combined the effect of the two elements together (sound and image) is more powerful and expressive than either could be presenting on its own. Key to understanding Chion’s argument is his theory of reciprocity between sound and image. One cannot act upon the other without being changed itself. Thus, sound in film reaches its full potential only through the lens of added value.

Another major concept from this book is that of synchresis. Chion coined this concept in reference to the “spontaneous and irresistible weld produced between a particular auditory phenomenon and visual phenomenon when they occur at the same time” (p. 63). He explains that synchresis occurs “independently of any rational logic”—as a law of audiovisual Gestalt—but he also calls it Pavlovian, because it is conditioned by the creator of the synchronized event. Furthermore, the theorist underlines that synchresis is not necessarily always rhythmic in nature, but it can also rely on meaning, which is dependent on “cultural habits” (p. 64). To understand this, let us consider the correspondence to the natural world: for example, we see a balloon popping and hear its effect as a simultaneous event. This is, in essence, an illusion since our eyes and ears receive the stimuli asynchronously due to the difference between the speeds of light and sound; then, the brain also processes them at different speeds; but the brain binds the two occurrences into one experience thanks to a process known as temporal recalibration. However, unlike the natural world, the audiovisual artist has the liberty to misplace or associate sounds and images. And, since our brains are used to merge aural and visual events, they make sense through synchresis. Obviously, in an artwork this relies in part on our suspension of disbelief because we realize that the amalgamation of dissimilar sounds and images is an artistic construct.

Metaphor-Based Models of Multimedia

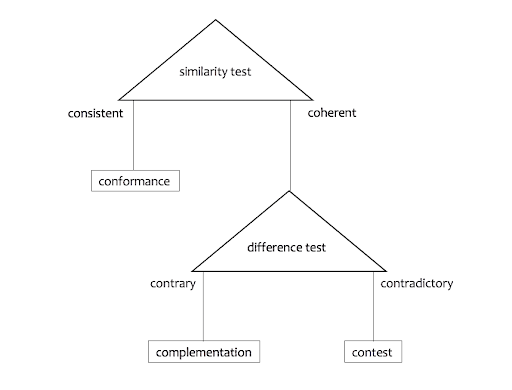

In Analysing Musical Multimedia (Cook, 1998), Nicholas Cook looks at multimedia as cooperation between semantically charged communication channels, underlining the role of music in audiovisual meaning-making. He proposes an analysis framework for cross-modal relationships based on correspondences between the media, or what he calls instances of multimedia. Considering each medium’s meaning in relation to another and arguing that a new meaning arises when layers work together—emergent meaning—Cook defines three metaphor-based models of multimedia.

To reach one of these three relationships one has to put the media, which in our case are the audiovisual layers, to a test. First is the similarity test: are the meanings of the music and the visuals consistent? If yes, then they exhibit conformance. If not, they are still coherent since they are presented together, so another test for difference is required: are the meanings contrary or contradictory? This results in the complementation and contest models.

Conformance

Complementation

Contest

Audiovisual Space

As a last theoretical point, I turn to Andrew Knight-Hill’s concept of audiovisual space. He argues that audiovisual theories based on temporal links cannot fully explain the richness of an audiovisual experience. In his article Audiovisual space: Spatiality, experience and potentiality in audiovisual composition (Knight-Hill, 2020), he proposes a reconceptualization of sound-image relationships as “complementary dimensions of a unified audiovisual space” (p. 49). He talks about a perceptual space—not panoramic space as in surround sound—which is a ‘virtual’ space constructed in the audience member’s mind and which replaces our normal visual field—a phenomenological space. The immersion in the audiovisual space of the work occurs, similar to cinema, through transcending the physical space and entering the space of the experience. His argument thus relies on spatial concepts and metaphors. Knight-Hill suggests that temporal constructs may be viewed rather as changes in space through movement—in either texture or gesture—and that expression can be found within trajectories constructed by spatial transitions. Gesture is then an externalized trajectory while texture is an internalized flux, both being dispositions of energy in space.

“Audiovisual space is constructed through the articulation of sound and image materials, a dynamic flux of energies unfolding through time. The ‘reality’ of perceived space is a result of these materials and their articulation” (p. 59).

The reason for bringing this paradigm to the table is that I appreciate Knight-Hill’s attempt to move beyond the analysis of separate consequent points in time and to consider overarching structures that form these audiovisual spaces. I believe that, within those spaces, the dimension of time is not eradicated and we can still apply the previous temporal analysis tools in parallel or in addition to the idea of a common perceptual space.

Video-Music-Performance

Argument

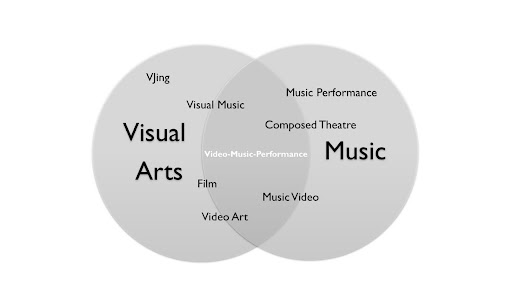

This is the point where I pivot and stop referring to the umbrella term audiovisual performance. Instead I propose a new term to designate a subgenre based on the practices that I have observed in works by living composers who implement video in music performance. In my own composition, I have devoted the past thirteen years to creating and investigating audiovisual relationships in what I call video-music-performance.

What I find powerful about the term audiovisual performance is precisely what also makes it problematic in my view: its general applicability. It encompasses too many different types of genres, technologies, practices, and contexts. It includes VJ culture, interactive visuals and electronic or electroacoustic music, light shows, laser shows, projection mapping with music performances, silent films with live music, etc. Essentially, any performance that includes sounds and visuals, live or recorded, can be referred to as audiovisual performance—whether it’s an artistic endeavor or not. For example, a TED presentation could be called an audiovisual performance since it includes audio (speech, maybe even music), visuals (slides, video), and it is a performed script.

In analyzing other composers’ works with video, I started noticing common threads between them, and also with my own work. So, in the following, I will expose my proposal for delineating this subgenre of video-music-performance. Because I will mention this term very often in the rest of the unit, I will abbreviate it as VMP. As one can notice, I decided to simply prepend the word video to the already established discipline of music performance in order to show the integration of this medium into the traditions, conventions, and practices of music performance.

Going forward, I want to underline two aspects of the digital age which I claim have had an impact on many living composers, as we will see today in examples of VMP. First, the supremacy of the visual culture and the increasing ease of capturing and disseminating videos today is reflected in the growing interest of composers to adopt and adapt moving images in their work. This is what prompted my research into this multimedia subgenre. Second, more and more elements from cyberculture are making their way into compositional practices—as they have done in other art forms for the past few decades, notably the visual arts and theatre—and they not only influence the aesthetics and methods for structuring sounds but also appear as distinct visual elements. Just as Alexander Schubert thoroughly presented in the unit History: Postdigital, the ‘digital’ has permeated every aspect of our lives and our cultures.

Delineating the Field

I assert that video-music-performance lives at the intersection of music performance, composed theatre, film and visual music, video art, and music video. And it inherits elements from all these art forms in various degrees.

As a subgenre of audiovisual performance, VMP continues the lineage of practices that combine sounds and image. Hence, it is preceded and informed by over a century of similar endeavors as we have seen earlier: color organs, avant-garde experiments of abstract filmmakers in the first half of the 20th century, the revolutionary video artists of the 1960s and 1970s, computerized visual music, Internet art and digitality. But its main distinctions from other audiovisual art forms are the centrality of live performance and the influence of, as well as overlap with the field of new music.

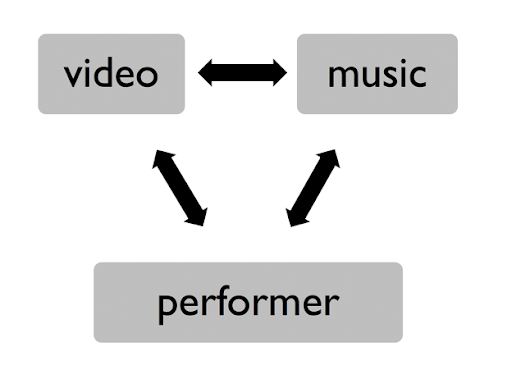

When composers work with video in performance they most often bring their musical background into the process as the primary way of structuring audiovisual relationships, as well as relationships between performers and electronic media. The way I look at these structural elements is through a concept I call symbiotic interrelation. This refers to the interactions that occur as a consequence of the performers, the electronic medium of video, and acoustic/electronic music inhabiting the same time and space of a performance. As we know from biology, different types of organisms can live together in a close and usually long-term interaction called symbiosis that is mutually beneficial. This partnership between performers, video, and music should be understood and analyzed in the context of a specific work and its overall concept and structure.

Thus, the main convention I set for demarcating this genre is that the interconnections between music, video, and performer should be observable in the following stages of a work:

- conception (composer/artist/creator/initiator),

- presentation (performer/improviser/co-creator), and

- reception (audience member).

I would like to give a few counterexamples that should clarify what I mean by this.

An old opera—let us take Mozart as an example—paired with novel video projections lacks the conceptual integration of the layers at the moment of conception. The interrelations that emerge between the music and the video projections, for instance, were most likely not considered by the composer at the time of creation. And, while also not coincidental—since some other artist has designed them in response to the music—I see the added projections as something closer to a music video that is created after the music is already completed. For this reason, I consider works that have not been created with both sonic and visual layers from the beginning to be outside of the scope of VMP.

During real time presentation on stage together with human performers, video—whether preproduced or live—showcases what Paul Sanden calls temporal liveness and spatial liveness (Sanden, 2013) and becomes a living part of the performance. As long as performers are aware of their relationship to the video and to the music, this condition is met.

For the final stage of reception, if one of the layers of the triumvirate (video <-> music <-> performer) is not visible or audible, then I consider that work not to be a VMP. For example, a composition that is based on a video score which the audience cannot see falls out of this genre because of the absence of performer-video relationships in the spectator’s perception. Notice in the following case two different performances of the same piece: one with the video score shown only to the performers, and the other one displaying the video score to the audience. Therefore, the former is not a VMP, while the latter is.

Furthermore, even if all three elements are there, it does not necessarily mean that a work engages these entities in sufficient meaningful relationships to stay within the border of the VMP subgenre. Let us take for example an audiovisual performance by Ryoji Ikeda.

Here we are missing something that Caleb Stuart describes in the Contemporary Music Review as “the body of the musician . . . directly and causally in a one-to-one relationship, acting on an object physically to create a sound” (Stuart, 2003). Or, in other words, there is a lack of embodied virtuosity. Also, a conceptual connection between the body of the performer and the visuals is not apparent. I make this distinction precisely to avoid the overlap with many audiovisual performance manifestations where the performer’s presence on stage is somewhat redundant (apart of course from generating live audiovisual material). By this I mean that we may just as well experience the work as a recording without the live performer on stage and the meaning of the work would not change radically. This is by no means a value judgment, but this kind of work can properly be referred to as audiovisual performance. In VMP, a work exhibits elements of composition, structure, and/or conceptual underpinnings that relate the performers’ bodies and/or personas to the audiovisual media so there is a perceived spatial/temporal and/or metaphorical interrelation between them.

For the rest of the unit, I will focus on the implementation of video in relation to music and performers, because we have already covered a fairly decent amount of music-video (sound-image) relationships in this unit, and music-performer is an area extensively examined in musicology.

The Screen

The embodiment of video on stage occurs usually through one or more screens. Whether it is an old CRT television set, a modern large-screen display (LCD, LED, OLED, etc.), a small-screen display such as that of a tablet or smartphone, a projection screen or a projection surface, even a VR headset, or a non-standard display, video becomes visible to the audience through a technologically mediated 2D or 3D frame. Lev Manovich (Manovich, 2001) provides a useful definition of the screen: “The visual culture of the modern period, from painting to cinema, is characterized by an intriguing phenomenon—the existence of another virtual space, another three-dimensional world enclosed by a frame and situated inside our normal space. The frame separates two absolutely different spaces that somehow coexist” (p. 95).

Thus, the frame of the screen hosts a virtual world on the stage along with the music performers. I want to propose three ways of describing the presence, integration, and significance of a video screen on stage. Each of them alters the perception of the music performers in different ways. It is common for two or all three meanings of the screen to be present in a piece. My categorization is based on what Vivian Sobchack described as the “three metaphors [that] have dominated film theory: the picture frame, the window, and the mirror” (Sobchack, 1992). The picture frame refers to formalist theories that consider the frame a synthetic space and insist on the artificial elements of cinema, such as ‘montage’ (editing). In contrast, the window metaphor is linked to realist theories which advocate an honest representation of reality. The screen as a mirror signifies the spectator’s identification not only with characters in the film but also with the apparatus of cinema (camera, projector, screen), which ultimately leads to identification with the self (Metz, 1981). My usage of these terms in the following categorization does not attempt to retain the strict original sense of the metaphors, but rather adjusts them as necessary for the practices of VMP.

Screen as picture frame can (re)contextualize the music performance. The video displayed on screen provides clarification or adds external meanings to the music performance.

Screen as window can virtually augment the stage and the performance. The stage and performers are connected to other worlds, possibly inhabited by other performers.

Screen as mirror can reflect the performers on stage. Among the works I have encountered, the most widespread and effective solution for video integration is the reflection—literal or figurative—of music performance or any aspect of it onto the screen. This metaphor of the mirror is so prevalent in VMP that it deserves special attention. There are in fact so many pieces with mirrored performers that I am almost tempted to suggest a sub-subgenre of VMP: perhaps it could be called meta-video-music-performance. But, for now, I will attempt a classification of screen reflections that I found in VMP works.

To aid my taxonomy, I turn to French philosopher Jean Baudrillard and his book Simulations and Simulacra (Baudrillard, 1994), in which he examines relationships between reality, symbols, and society, claiming that our current society has replaced all reality and meaning with symbols and signs, and that human experience is a simulation of reality. However, I have to admit this is going to be, again, a very speculative approach. Baudrillard distinguishes four levels of an image as simulation of reality and, for the purpose of looking at the screen as a mirror on stage in VMP, I make the following proposition based on Baudrillard’s four stages of the image.

1) “it is the reflection of a profound reality”

1a) for example, a photograph

1b) or the raw audio recording of an instrument

1c) in VMP: clones (faithful copies)

2) “it masks and denatures a profound reality”

2a) This could be a photograph that has been manipulated digitally

2b) in audio, a recording of an instrument may be edited/enhanced

2c) in VMP: doppelgängers (unfaithful copies)

3) “it masks the absence of a profound reality”

3a) an example may be a photograph that has been created digitally to simulate reality—hyperreality;

3b) a corresponding example in the realm of audio could be a recording of a digitally simulated instrument

3c) in VMP: avatars (virtual representations)

4) “it has no relation to any reality whatsoever; it is its own pure simulacrum”

4a) a digital image that has no correspondence in nature could fit in this category

4b) similarly, a recording of a synthesizer that does not sound like any known acoustic instrument would match this category

4c) in VMP: symbolic representations (metaphorical reflections)

Now that I have established the integration of video’s ‘body’ (the screen) on stage relative to the performers, I want to return to the diagram of interrelations and define a few categories that describe their interaction.

Interrelations between Video and Performer(s)

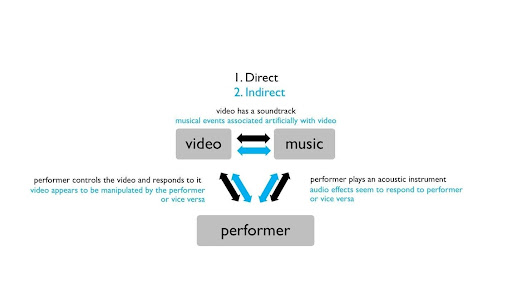

The two main categories of interrelations between the three entities in VMP refer to direct connections, when the three layers are intrinsically engaged with each other, and indirect connections that exist on an implicit level, when the layers seem to be connected but their associations are forged.

The issue of live vs fixed (prerecorded) video is also at stake here since a live video may appear more direct than a fixed one, although a meaningful performer-video link can be established with both types of material. Preproduced video seems to prevent any true interaction with the performers on stage, especially from the performer’s perspective. However, this is perhaps one of the most interesting areas, in my opinion, to be explored by composers working with video: creating artificial but meaningful interrelations between the living organism of human performer and the fixed medium of video.

Let us turn our attention, again, to the relationship between performer and video.

Direct connections

As direct connections, we can observe reactive and interactive elements. Because real interactivity between performer and video requires a process of mutual influence, I have noticed that it occurs less frequently in this strict sense in VMP. Instead, we as audience experience either some type of reactivity between musician and video or a fabricated interactivity crafted by the composer and enacted by the performer and the video.

a) Reactive connections

The video is created directly by the performer in real time:

As an example of the reverse situation, the performer is influenced by the video:

b) Interactive connections

Indirect connections

I classify these as illusory or metaphorical connections.

a) Illusory connections

Here the attempt is to convince the audience of a link between performer and video, either through the video itself or through the music.

b) Metaphorical connections

By metaphorical I refer to the associations between video and performer on a symbolic level. In this case, it is not an attempt to trick the audience’s perception but rather to invite them to discover deeper meanings.

Video-Music-Performance Off-Stage

As we get to the end of this unit, I want to pose a question in relation to the context of our current pandemic (at the time of writing): what happens when VMP cannot take place on a stage in front of an audience anymore?

Many musicians have fled to online performance formats in the past year while on lockdowns. The screen then swallows the entire visual aspect of the performance and the music is fully mediatized. How about the liveness? This year we have seen prerecorded and live streamed performances from artists’ homes, as well as documentation of performances or livestreams with artists physically present in empty venues as the audience tunes in from home. How does this alter the interrelations between video, music, and performers? In some ways, not much. If a performance is simply attempting to replicate what would have taken place on a stage in front of an audience, then it is possible to transport most of it from the frame of the stage to the frame of the screen (and from the acoustic space to the one reproduced by speakers/headphones). However, during this year of lockdowns, composers and performers have experimented with the idiosyncrasies of the online medium, while also staying close to traditional notions of physical performance. One important peculiarity of virtual VMP is that live performers are already virtual, so the immersive merging with other prerecorded virtual performers and digital entities becomes possible.

Why Video-Music-Performance?

A few conclusory thoughts about this proposed subgenre of video-music-performance and what it means for the three parties involved: composer, performer, and audience member.

For composers:

- There is a revived interest and tendency toward extra-musical elements.

- Experimentations in this field allow any combination, alteration, or negation of the inherited conventions from other related audiovisual genres, without displaying an intent to revolutionize but rather to create anew.

- Although the musical score is still central most of the time, audio and video channels offer composers ways of circumventing the need for notation, which can be enhanced or substituted by sonic and/or visual cues.

- Through techniques of customizing VMP works with preproduced or live video of the performers, composers find new ways of engaging with the musicians, accepting their impact in the work as collaborators.

For performers:

- VMP is also a gain for performers as they may become co-creators of the work by providing musical or visual input; so in a way this is an emancipation from the conventional role of the performer as solely an interpreter of the score.

- Performers’ corporeal presence on stage is often enhanced through the reflection of themselves in video or association with elements of the video.

- As a consequence of their relationship to the video, the practices and traditions of music performance can be invoked and reassessed, or ignored and replaced, for example, by more theatrical practices.

For audience members:

- The audience members are still often passive observers (at least in terms of being involved in the performance), but they are engaged in a keen intermodal immersion that triggers not only their knowledge of music, but also of film, theatre, popular culture, and so on.

- There is an opportunity to understand and experience musical relationships and performance elements from a visual perspective through the use of video; Michael Beil said video helps him “lead the attention of the audience to special parts of the musical performance”. So the audience can see connections between musical materials in time.

On a final note, I believe that the act of incorporating video in traditional music performance is part of postmodern, and more recently metamodern tendencies toward extra-musical elements. Metamodernism is a proposed movement that synthesizes key cultural, aesthetic, and philosophic elements from modernism and postmodernism, being simultaneous with the postdigital, postindustrial, global age. In short, it is a constant oscillation between opposing states, for example, being both sincere and ironic or naive and cynical. Meta here is used for its Platonian meaning of metaxis (in-between). In most of the examples of VMP I gave, the contextualization of music material through the presence of the video elements is not a cynical approach to creating new music but rather a natural extension of the artistic needs of composers. Thus, these audiovisual practices relate to the metamodernist spirit because they do not attempt to subvert traditional modes of performing music on stage. Instead, the use of video is generally reverential to music performance and its conventions. Even in cases when video seems to threaten the significance of the performers because of its dominance or inflexible nature, humans remain vital for the dissemination of live music.

This type of work proposes special ways of composing, performing, and experiencing music that invite techniques and meanings from outside of the musical world, aligning it with other multimedia genres. I would like to end with a quote from Gene Youngblood’s seminal book Expanded Cinema (Youngblood, 1970), which sums up my intention to persevere in creative and academic investigations of the video-music-performance subgenre: “One can no longer specialize in a single discipline and hope truthfully to express a clear picture of its relationships in the environment” (p. 41).

References

- Coulter, J. “Electroacoustic Music with Moving Images: The art of media pairing”. Organised Sound, 15(1), 26-34 (Retrieved June 30, 2021, from https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/organised-sound/article/electroacoustic-music-with-moving-images-the-art-of-media-pairing/FF94DC96F40A2C0AFFE9E483FD771448). 2010.

- Lachs, L. “Multi-modal perception. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology”. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. (Retrieved from http://noba.to/cezw4qyn). 2021.

- Higgins, D. “Intermedia”. Leonardo, 34(1), 49-54 (Retrieved June 30, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1576984). 2001.

- Phelan, P. “Unmarked: The politics of performance”. London: Routledge. 1993.

- Auslander, P. “Liveness: Performance in a mediatized culture”. London: Routledge. 1999.

- Klich, R. & Scheer, E. “Multimedia performance”. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. 2012.

- Dixon, S. “Digital performance: A history of new media in theater, dance, performance art, and installation”. MIT Press. 2007.

- Harrison, J. E. & Baron-Cohen, S. “Synaesthesia: An introduction. In S. Baron-Cohen & J. E. Harrison (Eds.), Synaesthesia: Classic and contemporary readings (pp. 3–16)”. Blackwell Publishing. 1997.

- Mollaghan, A. “The visual music film”. Palgrave Macmillan UK. 2015.

- Rogers, H. “Sounding the Gallery : Video and the Rise of Art-Music”. Oxford University Press. 2013.

- Newman, M. Z. “Video Revolutions : On the History of a Medium”. Columbia University Press. 2014.

- Westgeest, H. “Video art theory: a comparative approach”. John Wiley & Sons Inc. 2016.

- Vernallis, C. “Music Video’s Second Aesthetic?, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, 437-465”. Oxford University Press. 2013.

- Korsgaard, M. B. “Music Video Transformed, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, 501-521”. Oxford University Press. 2013.

- Chion, M. “Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen”. New York: Columbia University Press. 1994.

- Cook, N. “Analysing musical multimedia”. Oxford [England]: Clarendon Press. 1998.

- Knight-Hill, A. “Audiovisual spaces: spatiality, experience and potentiality in audiovisual composition, in Knight-Hill, Andrew, (ed) Sound & Image: Aesthetics and Practices”. Routledge, London, UK. 2020.

- Sanden, Paul. “Liveness in Modern Music: Musicians, Technology, and the Perception of Performance”. Routledge Research in Music. 2013.

- Stuart, C. “The Object of Performance: Aural Performativity in Contemporary Laptop Music”. Contemporary Music Review 22(4), 59–65. 2003.

- Manovich, L. “The language of new media”. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. 2001.

- Sobchack, V. C. “The address of the eye: a phenomenology of film experience”. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 1992.

- Metz, C. “The imaginary signifier: psychoanalysis and the cinema”. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 1981.

- Baudrillard, J. “Simulacra and simulation”. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. 1994.

- Youngblood, G. “Expanded cinema”. New York: Dutton. 1970.

- Eisenstein, S. & Pudovkin, V. & Alexandrov, G. “A Statement on Sound (USSR, 1928)”. Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures, edited by Scott MacKenzie, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014, pp. 565-568. 2014.